|

The All Party Parliamentary Group on Runaway and Missing Children and Adults is inviting interested individuals and groups to submit written evidence to its current inquiry into how the police, children's services, schools and other professionals safeguard children who are categorised as 'absent' from home or care or education. The inquiry is intended to examine how the introduction of the ‘missing’ and ‘absent’ categories has affected the safeguarding response to children who run away.

Ann Coffey MP raised concerns about the new absent category in her report published in October 2014 ‘Real Voices – Child Sexual Exploitation Greater Manchester’. The deadline for submissions of written evidence is Friday, 22 January 2016. You can find out more information here. Further reading: Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care. Report from the Joint Inquiry into children who go missing from care (June 2012).

0 Comments

Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

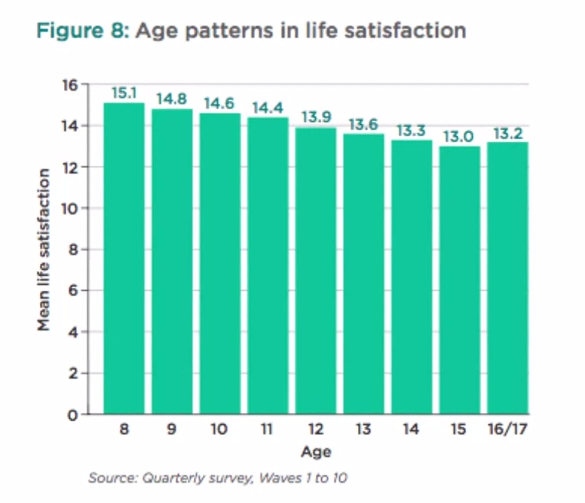

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence. Adolescence is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood and is a crucial developmental stage for our mental well-being. It is a period of physical, cognitive, social and emotional changes and it is important that adults supporting young people have a good grasp of the challenges they face. Physical changes in adolescence In 2013 The Good Childhood Report (The Childrens Society) charted the life satisfaction of a group of 8 to 17 year olds. They found that during this period life satisfaction declines. When it’s broken down the biggest drop seems to come from anxieties associated with physical appearance. Perhaps this isn't surprising considering that during puberty bodies’ change both in size and shape. Researchers have been debating a lot about whether and to what extent this may impact upon the body image and self-esteem of young people. While physical changes can be awkward for anyone, research suggests that adolescents who perceive their physical development as particularly early or late compared to their peers find it particularly difficult to adjust.

Brain development in adolescence While physical development can be quite obvious many parents and professionals are less aware that adolescence marks a period of profound cognitive development; a period of massive brain growth not seen since infancy. Recently research has been considering whether this can account for some of the common behaviours we see in teenagers: impulsivity, risk taking behaviours and intense emotions. Research has shown that it may have something to do with the pre-frontal cortex. In adults it is the part of the brain that helps us to maintain goal-directed behaviour, moderate intense emotional experiences and check our risky impulsive behaviour. Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence to indicate that purposive action selection depends critically on this particular region of the brain; however, it is also one of the last to develop. It is possible, therefore, that the risky and moody behaviour typically characteristic of this age group could have something to do with the late development of the pre-frontal cortex. Interpersonal relationships in adolescence Interpersonal development is a key stage in adolescence. It is a period of identify formation when young people become more oriented towards their peers, they individuate and separate, and become more autonomous from their family. Identity development correlates significantly with the quality of peer relationships, with their primary caregivers, and with any younger people who are around them. Interpersonal development is crucial in adolescence, and a lot of the psychological resilience and vulnerability manifest here. Transition points between primary and secondary school, residential moves or any other circumstance that forces the adolescent to re-establish themselves within a new peer group are absolutely key. A lot of their personal identity development is who they are to others, and often the most important people to a young person are their peers and who they are to other young people around them. We can also see a high level of compartmentalization in adolescent social circles. That is to say, adolescents can often be somebody completely different to their families, to who they are to friends, to who they are at extra-curricular activities. That is one of the reasons why the quality of a young persons relationships and their social environment is so important and why experiences, such as bullying or social isolation, can have such a profound impact on a young person's mental health and well-being. One of the things that comes with emerging independence, and with individuating as a young person, is the formation of different bonds and different types of relationships. Indeed, the emergence of romantic relationships, and active and romantic feelings, are crucial. This is why it is important that young people have positive and healthy experiences. They are very vulnerable to exploitation and negative experiences which, again, can have a profound effect on their mental health and well-being. Young people tend to experiment a lot with intimate relationships, with romantic relationships, and different types of peer relationships. Sometimes it can be difficult for young people, when identities aren't fully formed and they are less clear about who they are to others, to know how to define these – are they a boyfriend/girlfriend, friend, sporting team mate? These difficulties and uncertainties can make them increasingly vulnerable in relationships where there is a disparity of power. Traditionally adolescence has been discussed and defined as a period of storm and stress. We expect high levels of conflict experimentation; a lot of adolescent identity development is in opposition to what is expected of them. Adolescents can be inter-personally challenging and difficult both within their families, within institutions, and any other contexts that they may find themselves in. They usually struggle with ideas of identity, conformity, and indifference. It is intensely difficult for young people to appreciate how they're perceived by others yet, at the same time, it's also very important to them. Adolescent development waxes and wanes, they can go from moratorium and uncertainty to premature identity formations. It is, therefore, important for parents, carers and professionals to consider these dynamic stages, as premature pinning of expectations can be quite detrimental. A couple of weeks ago I was asked about the causes, symptoms and likely consequences of troublesome and antisocial behaviours in children and young people. I’ve put together this post to offer a little bit of insight and advice to parents and those working with children displaying these kinds of behaviours. I hope that this post will help you by:

Nearly all children and young people can react in an angry or aggressive way if they are provoked. This ability is essential for survival, otherwise people would have difficulty defending their need for space and food. That is not what this post is concerned with; rather we are looking at cases where children are aggressive and angry a lot of the time. Children that do this far more than others, and in a way that prevents them from making satisfying relationships and getting on with activities and schoolwork. Before we get started I think it is important to firstly distinguish antisocial behaviour from the following: Occasional acts of antisocial behaviour or temper outbursts, once a fortnight or month, can be very frustrating for parents or teachers. However, if the child is well adjusted, has friends and is doing okay at school: adults should react calmly and not make too big a deal of what has happened; respond quietly (shouting at the child and calling them names can do more damage than the child’s original outburst); stay calm and apply a consequence that lasts a short time but is important to the child (for example, taking away a mobile phone, grounding the child or stopping them watching TV); talk when both sides have calmed down, about what happened and try to find ways to stop it happening again in the future. New antisocial behaviour in a previously well-adjusted child. This could include longer periods, up to a month or two, of aggression and moodiness in a previously reasonably adjusted child that after investigation seems to have a fairly obvious cause for the change in behaviour. For example: separating parents, failing an exam, breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend, moving to a new area or being bullied or abused. In these cases, adults should find a calm moment to talk to the child and discover what is on their mind; suggest possibilities to the child, as he or she may not be aware how upsetting an event has been; make the child feel that they are understood and there is sympathy for them; once the causes has been agreed, make plans for a more positive future. Usually the behaviour will settle down; if it doesn't, then a more significant problem should be considered. Long-standing antisocial behaviour can be defined as a general pattern of antisocial behaviour that has been present for several months in children and young people. In younger children this pattern can include: being touchy, having tantrums and being disobedient; breaking rules, arguing and rudeness; deliberately annoying other people, hitting, fighting, and destroying property around the house or school; or, bullying other children. If the pattern is persistent and serious enough to reduce the child’s ability to have a happy home life and/or get on at school, then the child is likely to meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. In older children and teenagers this pattern can include: lying and stealing (including breaking and entering into houses) and cruelty to other people or animals; leaving the house without saying where they are going (staying away overnight without permission); skipping school (truancy) or breaking the law, drinking alcohol inappropriately or taking drugs inappropriately; being a member of a gang and/or carrying a weapon. If the pattern is persistent and serious they are likely to meet criteria for a conduct disorder. The long-term consequences of a conduct disorder are often negative and the child may be at significant risk of: criminal and violent acts; misusing drugs and alcohol; leaving school with few qualifications; or becoming unemployed and dependent on state benefits. It is, therefore, important that those working with children and young people are able to identify those who are at risk so that effective interventions are available. If you are worried a child is displaying signs of oppositional defiant disorder or a conduct disorder you should seek a referral to CAMHS through the child’s GP. Many children and adolescents behave in a difficult or aggressive way from time to time. However, a minority do this persistently for several months in a way that hurts other people emotionally or physically. This can result in poor relationships with family, friends and peers at school. Young children may be very difficult to handle at home but perfectly well behaved at school. A small minority are the other way around. If problems persist they often spill out from home to include school and relationships with friends, who get fed up with the aggression. Bullying, for example, may happen during the school day or on the journey to and from school. Teenagers may go out into the local community in gangs and commit antisocial acts. There are many possible underlying causes of persistent anti-social behaviour. The first step in assessment should be to speak with the child or young person about their behaviour as well as any upsetting external events in their life. Parents and teachers are also a great source of information and insight regarding a child’s well-being. If a child has been performing worse than expected in school, it may be that they have a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia with reading. It is not necessarily the case that poor performance is due to laziness and failure to apply themselves. If a child is restless and fidgety, has difficulty sitting still and moves around more than other children, it is possible that they suffer from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). If present, the child will also have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating. They will not be able to control themselves in a wide range of situations such as queuing up at school, or taking turns in conversation. Schools should be able to refer children displaying these behaviours for assessment by an educational psychologist. If a child is persistently sad and miserable, it is possible that they are suffering from depression. If this is a concern you should request additional support through your GP. You may also find my article on Attachment Based Family Therapy useful. Ineffective parenting is often a strong contributor, particularly if there is little warmth or positive encouragement; low involvement and poor supervision of the child’s activities and whereabouts; inconsistently applied consequences; or negative and harsh discipline. Certain types of parenting are more likely to lead to antisocial behaviour either initially, or in maintaining it. For example, through inconsistent discipline the child may learn that they often get what they want by misbehaving, which in turn reinforces the behaviour. In many cases it may be that parenting is not ‘ideal’. This may arise simply out of exasperation, where the child is so annoying that the parents lash out angrily. Even if the original cause of the behaviour was an unhappy event, or a difficult temperament, if the child learns that he or she is rewarded by getting what they want through misbehaving they will do it more often. When children get little attention, they prefer to have negative attention than none at all. They will misbehave to gain the interest of the parent, even if through scolding or telling off. Reversing it provides a way forward for treatment. The way to reverse bad behaviour is to help parents build a positive relationship with their child. The parent should be supported in making clear the behaviour they want from the child and reward them through attention, praise or other good things. When the child does not behave, parents should use calm limits with clear consequences. Minor misbehaviour should be ignored whilst there should be proportionate consequences if it is more serious. Children must be given plenty of attention and encouragement for positive behaviour. This means instead of saying ‘stop running’ say something like “please walk slowly”, or “I really like it when you walk calmly”. If the child is making a mess at the dinner table, rather than saying “stop making such a mess”, you should give clear instructions as to what is desired and then praise them. These instructions are very clear and help the child understand what is required. Praise should be immediate as it allows the child to see a clear link between cause and effect. Barefoot Social Work can provide support on effective interventions, and an action plan can be formulated for your child or young person. Usually these work by helping parents and others around the child set clear limits and encourage positive behaviour. However, sometimes they can also help the young person learn techniques to control their temper. It may be that parenting classes will be beneficial or a period of intensive one-to-one parenting support. Please get in touch if you require any additional advice. Finally, it is important to note that if behaviour is suspected as being the result of abuse it is essential that concerns are reported to your local authority children’s safeguarding service.  Last week I started a 6 week course with the University of Edinburgh called The Clinical Psychology of Children and Young People. Child psychology is an area that particularly interests me and I'll post some of my own interpretations of how the material can be used in social work practice. I have studied it extensively in the past; however, I believe that as Social Workers we should continually refresh and build upon the knowledge that forms a basis for our practice. Like renewing a first aid certificate. I hope you find these posts interesting and helpful. This week we looked a child and adolescent development, factors that influence development, and models of developmental psychopathology. An understanding of children’s development helps us to interpret children’s well-being and mental health, and taking a developmental approach is important as it helps us to spot and interpret a number of different patterns and behaviours. Furthermore, looking at developmental outcomes (milestones) allows us to see when development is atypical and helps us to identify ways in which the child may need supporting. Children are qualitatively different from adults, they are not born as mini adults, and they are not born as empty vessels. They are complex in their development: some development occurs slowly and over time; other times development occurs rapidly such as in infancy and adolescence. To help, we can break it down into the following phases of development:

There are also different aspects of development:

Of course, the child develops as a whole and the different aspects of development do not occur in isolation. They all interact with one another. To understand this we look at patterns of development. Development isn't always progressive. There are various patterns of continuous change. Sometimes development can be very rapid and sometimes change is slow and gradual. At 18 months children start to engage in pretend play. Pretend play starts to decline during middle childhood as other forms of play become more prominent. This pattern of continuous development is often known as an inverted U function; where you can see that development increases and then declines. You can also have U shaped continuous change where you see an apparent decline that actually leads to an improvement in development. Often this is true of cognitive development where a child’s behaviour may look like it is becoming more difficult but actually, cognitively, they are re-evaluating how to perform the task and then their performance improves. Another pattern of development is stage changes. This is where you have changes in ability which seem to take quite a dramatic shift. A classic theory of stage changes is Piaget’s theory of development. He outlined four stages of cognitive development:

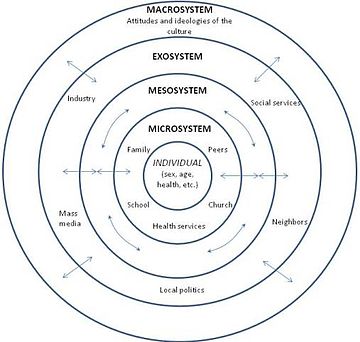

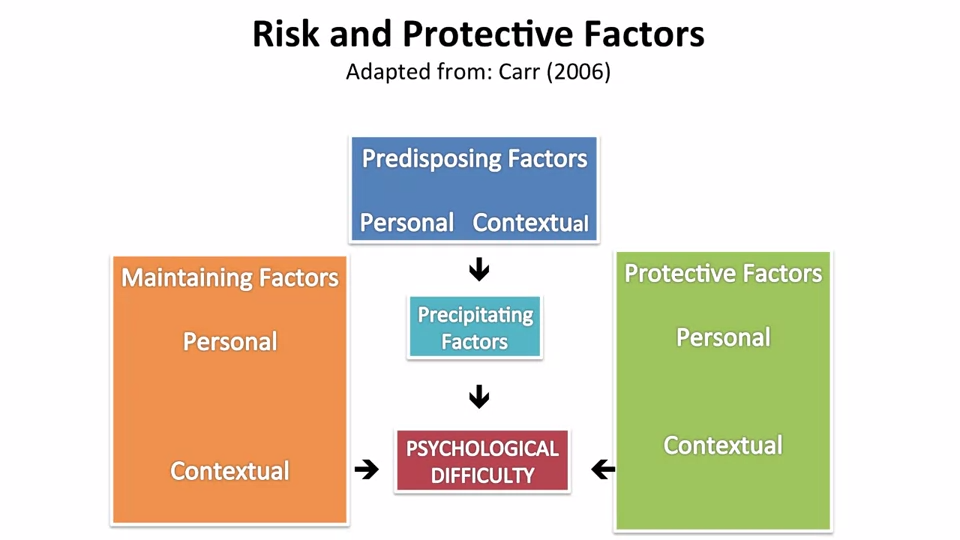

Piaget argued that each of these stages is typified by a new range of cognitive abilities or operations that allow children to cognitively perform at a different level. There are many influences on development. Firstly, biological influences like genetics and the brain. Genetics have a probabilistic relationship with development. They do not always determine or cause different developmental outcomes but they influence it through interacting with other genes and other things in our environments. An example of where genetics do have a direct link with development is in Down Syndrome. It’s a chromosomal abnormality that lead to a particular set of features and characteristics. Most genetic contributions are, however, probabilistic and they are seen as a risk or protective factors rather than direct causes. Twin research studies have been helpful in assessing the relative role of genes versus environment. As a result some mental health conditions and difficulties have been found to have a genetic component to them. For example, schizophrenia, ADHD, Autism, developmental dyslexia. However, genes aren't the whole story they are just a part of it. The Human Genome Project has helped to identify which genes or constellation of genes influence particular developmental and mental health outcomes. For example, we now know particular genes are involved with autism. We also know that some genes and combinations of genes act as protective factors as well. Brain development is also a significant biological influence. We know that there are important growth spurts which occur in the brain, firstly in infancy, and then later in adolescence. In the first two years of life we know that the brain grows enormously; but even more important are all the connections that are made in the brain that are related to the experiences the child has both physically, socially and emotionally. The more experiences a child has the more connections are maintained. If those experiences don’t occur or are reduced then the synaptic connections are pruned. This means that early brain development in infancy is very much a product of the environment the child is in; but in turn that brain development itself offers developmental opportunities for the child. The next major changes in brain development occur in adolescence which coincide with puberty. I’ll write a separate post on this later. Biological influences are really important but the environments within which children live and the people they live with are crucial to their development. We refer to these as social and environmental factors. Not only do the people a child lives with influence the food they eat (whether they have enough), the house and community they live in but also the people around them give them opportunities to learn and improve their understanding of the world and themselves. Also the people around them help them to form relationships and emotional bonds with others which can last in the long term. Social workers can use a tool (based on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological systems theory) to assess a child’s social and environmental factors. A child can complete a task with concentric circles with them in the middle; identifying who they think are important to them. Most importantly you should ask the child why they feel they are important. The third influencing factor on development is the interactions between biological, psychological and social influences. Most of a child’s development is influenced by both biological and social factors and how they interact. This area is often called the nature / nurture debate. For example, in early infancy, experiencing a loving, caring relationship with someone is crucial to the development of attachments. If this area is of particular interest you might like my posts on Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nurture and Nurture. Finally, we looked at models of developmental psychopathology and it’s influences on mental health and well-being. Developmental psychopathology focuses on normal and abnormal development and also adaptive and maladaptive processes. It shows us that there are a range of developmental trajectories that a child can take. Compas and colleagues undertook a review of adolescent development and highlighted that there isn’t just one developmental pathway or trajectory. They identified five:

This model is important as it highlights that adolescent development doesn’t just have one pathway. There are a range of different pathways that young people can find themselves on depending on a range of different factors and influences. Social Workers work with children and use skills based upon child development in their everyday practice. We observe children and learn something about how they’re developing and their well-being from our observations of them. We speak to children and learn about their development directly from them. We sometimes use little tasks and drawings and even short questionnaires and scales. If you'd like to find examples of scales and questionnaires that might be helpful in your practice please take a look at the tools section of this website.

Next week I'll be covering the topic of resilience. Please follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss it! Adolescent 'behavioural problems' are a huge source of referrals for local authority children's services across the country, after parents and teachers struggle to find strategies that work. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that many rebellious and unhealthy behaviours or attitudes in teenagers can actually be indications of depression. The following are just some of the ways in which teens “act out” or “act in” in an attempt to cope with their emotional pain:

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) has been the traditional route for support in the UK. However, waiting times and thresholds are at an all time high. More and more services are commissioned only for those children presenting with the signs and symptoms of a diagnosable disorder or condition which means that those struggling with less obviously acute or harder-to-label problems are often not eligible for treatment. As a result Children’s Social Workers are increasingly working to help families through what can be a very distressing time, and there is a renewed focus on specialised training to meet this need.  Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) is a manualised, empirically informed, family therapy model specifically designed to target family and individual processes associated with adolescent depression. However, I have found it has strong applicability when working with all families with teenagers. It was first developed by Prof. Guy Diamond, Suzanne Levy and Gary Diamond; all of whom have received international acclaim for their work in this area. The model is emotionally focused and provides structure and goals; thus, increasing the Social Workers intentionality and focus. It has emerged from interpersonal theories that suggest teenage depression can be precipitated, exacerbated, or buffered against by the quality of interpersonal relationships in families. It is a trust-based, emotion focused model that aims to repair interpersonal ruptures and rebuild an emotionally protective, secure-based, parent-child relationship. Teenagers may experience depression resulting from the attachment ruptures themselves or from their inability to turn to the family for support in the face of trauma outside the home. The aim of ABFT is to strengthen or repair parent-child attachment bonds and improve family communication. As the normative secure base is restored, parents become a resource to help their child cope with stress, experience competency, and explore autonomy. I believe it should be integrated into the practice of all children’s social workers. If you’d like to learn more you can buy the latest book, Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Depressed Adolescents, here. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|