|

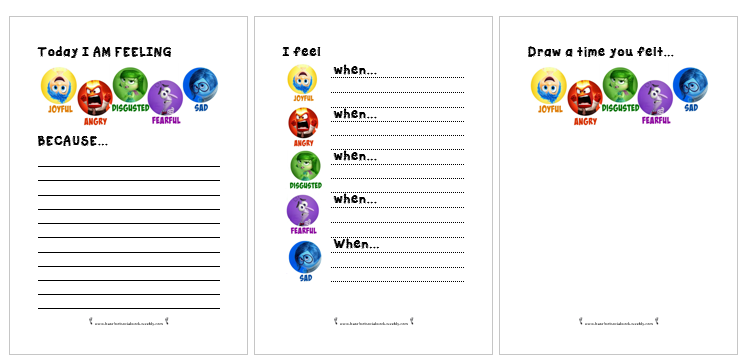

A year or so ago, I remember reading an article on The New Social Worker by Addison Cooper about ‘How Movies Can Help in Working with Kids’. If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do. It won’t take very long. Basically, she talks about how ‘movies can provide an excellent and easy way to connect with clients’ and ‘provide them with understandable analogies’. I think most Children’s Social Workers draw upon popular culture in their work. Cbeebies characters provide a universal conversation starter for most pre-schoolers and The X Factor is usually good with Teens. But we can also, as Addison points out, use them to help children understand their own emotions and circumstance. This summer’s movie Inside Out has received fantastic reviews and looks like a brilliant resource and tool for Social Workers. Take a look at the trailer if you haven’t already seen it. An article in The Guardian calls it a crash course in PhD Philosophy of self. It tells the story of 11 year old Riley, who moves to a new city and tries to make sense of her environment. The central characters Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust live in Headquarters, the control centre inside Rileys mind. Of course, in reality, there are more than just five emotions but that would have made the storyline a little too complicated. Whilst initially viewers may perceive most to be negative emotions, as the movie progresses we see how they work together and play an important role in keeping Riley safe. A message that Social Workers will understand and be able to relate to in their practice. During one scene Joy tells Sadness, drawing a small circle around the blue character, “your job is to make sure that all the sadness stays inside of it”. I find this quite profound as it is often what we see children encouraged to do when they are struggling with their emotions. Sadness and Anger can manifest in all sorts of ways that society perceives to be negative. Schools and classrooms aren't always set up to deal with the individual emotional needs of a pupil when their behaviour is seen to be impacting upon the learning of others around them. So, they are encouraged to ‘behave’, ‘be quiet’ and ‘calm down’. Hopefully Inside Out will help others to interpret children’s actions and foster empathy. It might also resonate with parents struggling to understand their child and how they can best support them. I’ve put together a couple of resources that you might like to use. Please feel free to download and share. Amazon also sell figures that could be incorporated into direct work or you can print off some of the colouring pages from the Disney website.

1 Comment

Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|