|

As part of my research I have been looking at the construction of parenting and, specifically, mothering. How expectations of the parenting role has changed over time and how this has shaped and been shaped by government policy and legislation. I'm going to try and blog about pieces that I think will be particularly interesting to Social Workers, as I know quite a few of you follow my page, but I'll try not to bombard you too much with academic content.

Today I read The Social Work Assessment of Parenting: An Exploration by Johanna Woodcock. Although it was published in the British Journal of Social Work over a decade ago (2003) I believe her findings are still relevant today and would be a good read for any practitioner wanting to reflect upon their own construction of parenting and practice. Woodcock’s paper draws on a qualitative study of Social Workers conceptualisations of parenting and the relationship this construction has with practice. Within her exploratory study, Social Workers were asked to describe and give their opinions on the parenting that occurred within a case that they brought forward. Analysis of the data she obtained revealed four types of expectations that underlay judgements of parenting deemed both ‘good enough’ and ‘not good enough’. 1. The expectation to prevent harm. Woodcock found that Social Workers were influenced by legal or quasi legal constructions of parenting. Their overriding concern was the capacity of the parent to prevent harm and relied upon the presence or absence of evidence of ‘physical abuse’ ‘emotional abuse’, ‘sexual abuse’ or neglect in making this judgement. 2. The expectation to know and be able to meet appropriate developmental levels. Woodcock found that Social Workers attributed a parent’s failure to protect their child from harm to their limited understanding of their child’s stages of development. Woodcock highlighted the narrative from one case where a parent and social worker were unable to agree on the level of appropriate supervision. A second area of Social Worker concern manifested when a delay in growth and development was deemed to be the result of poor parenting. 3. The expectation to provide routinised and consistent physical care. Parents were expected to appreciate the importance of routines and demonstrate their capacity to carry them out Woodcock found that routines were a key element of Social Work discourse. ‘Not meeting the child’s needs’ invariably referred to a lack of routine and consistency and that the child’s emotional needs for a sense of safety and security were not being met. 4. The expectation to be emotionally available and sensitive. For some Social Workers it was insufficient for a parent to simply love a child. They needed to have more insight into the emotional reasons for a child’s behaviour, which took them beyond physical care and to demonstrate a level of affect and interest in the parent-child interaction. Woodcock also looked at the Social Workers’ ‘psychological appreciation’ of the parent. She found that one way in which social workers made sense of problem parenting involved whether the parent was psychologically ‘damaged’ or ‘disturbed’ through abuse, or a lack of consistency or emotional warmth in their own childhood. Alternatively, early experiences were seen to provide modelling for future parenting and the absence of a positive role model accounted for their lack of ‘knowledge'. Importantly, Woodcock noted that these explanations draw on two implicit competing theoretical orientations: psychoanalysis and social learning theory; and despite being assimilated into assessment this evidence base was not evident in intervention or treatment. Conversely, Social Workers relied on exhorting parents to change or ‘getting them’ to take responsibility. She found little evidence of attempts through intervention to address these deeply ingrained psychological needs, either through direct social work or referral to psychological services. When psychologists were called upon it was to contribute an opinion with regard to the parent’s capacity to change rather than to help facilitate that change. Woodcock asserted that it was this incoherence between the intervention strategy and the social workers construction of parenting which inevitably led to resistance. Somewhat ironically, it is also resistance and an ‘inability to work with agencies’ that compounds an assessment of poor parenting. The main concern for practitioners should be Woodcock’s identification of a ‘surface static’ notion of parenting. A surface response means that the psychological factors underlying parenting problems remain unresolved. By relying on exhortation to change, rather than responses informed by psychological observations, Social Workers create an environment that is unconducive to change and thus perceptions of parent ‘resistance’ more likely. An explanation offered by Woodcock for the presence of a ‘surface-static model’ is the fact Social Workers are increasingly directed to their legal responsibilities to ensure the protection of the child from harm, rather than on problems that beset the parent. This professional quandary has, in my opinion, only worsened in the intervening decade and is something that government needs to address if outcomes are to improve. Social Workers need to reject the current political rhetoric surrounding parenting which places responsibility for child outcomes with parents, whilst underplaying socio-economic factors. On a practice level, Social Workers can consider what constructs they being to an assessment and whether their work reinforces a static notion of parenting. Try and incorporate these questions into your reflective practice: Am I focussing solely on assessment and parental behaviour, or am I actively seeking to enhance parental capacity through improvements in the problems that beset the parent. I imagine this would be an interesting discussion in supervision.

2 Comments

As some of you will already know, I am a Social Worker and Blogger here at Barefoot Social Work . I am particularly interested in adverse childhood experiences and finding ways in which children and their families can be supported to mitigate their negative long term affects. I am passionate about supporting children to remain in the care of their family and I believe strongly that local services should be available to make that happen. That is why I am particularly concerned (and have blogged) about austerity and the impact this will have on vulnerable children and their families. I believe Social Workers should help shape the political debate about issues that affect the people we support. We can do this in a number of ways: private conversations, engaging with media outlets, campaigning, petitioning and social research (to name a few).

Last week I was offered the very exciting opportunity to undertake a Phd at Manchester Metropolitan University. My study will look at 'Enabling Families in Austere Times' and will include a detailed ethonographic exploration of Home Start in England. The austerity narrative dominates the shaping of social care services and families’ experiences of care within Britain. Anxiety and insecurity are prevailing aspects of contemporary life and research highlights the negative impact on low and middle-income families. Government policy and the recent conservative budget increasingly emphasises the importance of ‘good’ parenting, with parents being expected to be responsible citizens, bear the impact of austerity measures, and take the blame for a myriad of societal issues. Third sector organisations play significant roles in the delivery of social care, particularly within a landscape of welfare state retrenchment and pressure on support services. However, there are significant gaps in empirically-based research that clarifies the distinctiveness of organisations. Home-Start has been the focus of limited research focused on enhanced children’s school readiness (Love et al., 1976) and improvements in children’s behaviour (Hermans et al., 2013). Existing research does not focus on the role that Home-Start performs in local communities, the diversity of families or the experiences of volunteers. In 2014 my research supervisor, Jenny Fisher and colleagues, undertook a small-scale evaluation of Home-Start Manchester South. This identified that they provide an invaluable support for families experiencing difficulties across South Manchester through the role of volunteers. The main aim of my research is to build upon the previous research and interrogate the impact of Home-Start on families in austere times. This will develop an empirically and theoretically sound understanding of family support and characteristics of Home-Start in supporting families. If you have followed the news around Kids Company over the last couple of weeks you will understand how important it is that organisations are accountable to those that invest personally and financially, and are able to evidence outcomes and efficacy. I am very excited about this opportunity and I am honoured that Manchester Metropolitan University and Home Start are supporting this research. I will start in September and would really appreciate your support. Please take a look at my fundraising page. If anyone is interested in following the progress of my research, I will be posting regular updates on my blog . Please follow me on twitter and facebook . Thank you x A couple of weeks ago I was asked about the causes, symptoms and likely consequences of troublesome and antisocial behaviours in children and young people. I’ve put together this post to offer a little bit of insight and advice to parents and those working with children displaying these kinds of behaviours. I hope that this post will help you by:

Nearly all children and young people can react in an angry or aggressive way if they are provoked. This ability is essential for survival, otherwise people would have difficulty defending their need for space and food. That is not what this post is concerned with; rather we are looking at cases where children are aggressive and angry a lot of the time. Children that do this far more than others, and in a way that prevents them from making satisfying relationships and getting on with activities and schoolwork. Before we get started I think it is important to firstly distinguish antisocial behaviour from the following: Occasional acts of antisocial behaviour or temper outbursts, once a fortnight or month, can be very frustrating for parents or teachers. However, if the child is well adjusted, has friends and is doing okay at school: adults should react calmly and not make too big a deal of what has happened; respond quietly (shouting at the child and calling them names can do more damage than the child’s original outburst); stay calm and apply a consequence that lasts a short time but is important to the child (for example, taking away a mobile phone, grounding the child or stopping them watching TV); talk when both sides have calmed down, about what happened and try to find ways to stop it happening again in the future. New antisocial behaviour in a previously well-adjusted child. This could include longer periods, up to a month or two, of aggression and moodiness in a previously reasonably adjusted child that after investigation seems to have a fairly obvious cause for the change in behaviour. For example: separating parents, failing an exam, breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend, moving to a new area or being bullied or abused. In these cases, adults should find a calm moment to talk to the child and discover what is on their mind; suggest possibilities to the child, as he or she may not be aware how upsetting an event has been; make the child feel that they are understood and there is sympathy for them; once the causes has been agreed, make plans for a more positive future. Usually the behaviour will settle down; if it doesn't, then a more significant problem should be considered. Long-standing antisocial behaviour can be defined as a general pattern of antisocial behaviour that has been present for several months in children and young people. In younger children this pattern can include: being touchy, having tantrums and being disobedient; breaking rules, arguing and rudeness; deliberately annoying other people, hitting, fighting, and destroying property around the house or school; or, bullying other children. If the pattern is persistent and serious enough to reduce the child’s ability to have a happy home life and/or get on at school, then the child is likely to meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. In older children and teenagers this pattern can include: lying and stealing (including breaking and entering into houses) and cruelty to other people or animals; leaving the house without saying where they are going (staying away overnight without permission); skipping school (truancy) or breaking the law, drinking alcohol inappropriately or taking drugs inappropriately; being a member of a gang and/or carrying a weapon. If the pattern is persistent and serious they are likely to meet criteria for a conduct disorder. The long-term consequences of a conduct disorder are often negative and the child may be at significant risk of: criminal and violent acts; misusing drugs and alcohol; leaving school with few qualifications; or becoming unemployed and dependent on state benefits. It is, therefore, important that those working with children and young people are able to identify those who are at risk so that effective interventions are available. If you are worried a child is displaying signs of oppositional defiant disorder or a conduct disorder you should seek a referral to CAMHS through the child’s GP. Many children and adolescents behave in a difficult or aggressive way from time to time. However, a minority do this persistently for several months in a way that hurts other people emotionally or physically. This can result in poor relationships with family, friends and peers at school. Young children may be very difficult to handle at home but perfectly well behaved at school. A small minority are the other way around. If problems persist they often spill out from home to include school and relationships with friends, who get fed up with the aggression. Bullying, for example, may happen during the school day or on the journey to and from school. Teenagers may go out into the local community in gangs and commit antisocial acts. There are many possible underlying causes of persistent anti-social behaviour. The first step in assessment should be to speak with the child or young person about their behaviour as well as any upsetting external events in their life. Parents and teachers are also a great source of information and insight regarding a child’s well-being. If a child has been performing worse than expected in school, it may be that they have a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia with reading. It is not necessarily the case that poor performance is due to laziness and failure to apply themselves. If a child is restless and fidgety, has difficulty sitting still and moves around more than other children, it is possible that they suffer from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). If present, the child will also have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating. They will not be able to control themselves in a wide range of situations such as queuing up at school, or taking turns in conversation. Schools should be able to refer children displaying these behaviours for assessment by an educational psychologist. If a child is persistently sad and miserable, it is possible that they are suffering from depression. If this is a concern you should request additional support through your GP. You may also find my article on Attachment Based Family Therapy useful. Ineffective parenting is often a strong contributor, particularly if there is little warmth or positive encouragement; low involvement and poor supervision of the child’s activities and whereabouts; inconsistently applied consequences; or negative and harsh discipline. Certain types of parenting are more likely to lead to antisocial behaviour either initially, or in maintaining it. For example, through inconsistent discipline the child may learn that they often get what they want by misbehaving, which in turn reinforces the behaviour. In many cases it may be that parenting is not ‘ideal’. This may arise simply out of exasperation, where the child is so annoying that the parents lash out angrily. Even if the original cause of the behaviour was an unhappy event, or a difficult temperament, if the child learns that he or she is rewarded by getting what they want through misbehaving they will do it more often. When children get little attention, they prefer to have negative attention than none at all. They will misbehave to gain the interest of the parent, even if through scolding or telling off. Reversing it provides a way forward for treatment. The way to reverse bad behaviour is to help parents build a positive relationship with their child. The parent should be supported in making clear the behaviour they want from the child and reward them through attention, praise or other good things. When the child does not behave, parents should use calm limits with clear consequences. Minor misbehaviour should be ignored whilst there should be proportionate consequences if it is more serious. Children must be given plenty of attention and encouragement for positive behaviour. This means instead of saying ‘stop running’ say something like “please walk slowly”, or “I really like it when you walk calmly”. If the child is making a mess at the dinner table, rather than saying “stop making such a mess”, you should give clear instructions as to what is desired and then praise them. These instructions are very clear and help the child understand what is required. Praise should be immediate as it allows the child to see a clear link between cause and effect. Barefoot Social Work can provide support on effective interventions, and an action plan can be formulated for your child or young person. Usually these work by helping parents and others around the child set clear limits and encourage positive behaviour. However, sometimes they can also help the young person learn techniques to control their temper. It may be that parenting classes will be beneficial or a period of intensive one-to-one parenting support. Please get in touch if you require any additional advice. Finally, it is important to note that if behaviour is suspected as being the result of abuse it is essential that concerns are reported to your local authority children’s safeguarding service. Adolescent 'behavioural problems' are a huge source of referrals for local authority children's services across the country, after parents and teachers struggle to find strategies that work. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that many rebellious and unhealthy behaviours or attitudes in teenagers can actually be indications of depression. The following are just some of the ways in which teens “act out” or “act in” in an attempt to cope with their emotional pain:

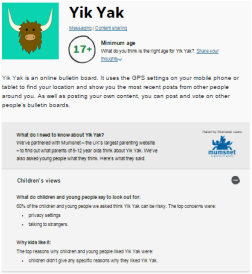

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) has been the traditional route for support in the UK. However, waiting times and thresholds are at an all time high. More and more services are commissioned only for those children presenting with the signs and symptoms of a diagnosable disorder or condition which means that those struggling with less obviously acute or harder-to-label problems are often not eligible for treatment. As a result Children’s Social Workers are increasingly working to help families through what can be a very distressing time, and there is a renewed focus on specialised training to meet this need.  Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) is a manualised, empirically informed, family therapy model specifically designed to target family and individual processes associated with adolescent depression. However, I have found it has strong applicability when working with all families with teenagers. It was first developed by Prof. Guy Diamond, Suzanne Levy and Gary Diamond; all of whom have received international acclaim for their work in this area. The model is emotionally focused and provides structure and goals; thus, increasing the Social Workers intentionality and focus. It has emerged from interpersonal theories that suggest teenage depression can be precipitated, exacerbated, or buffered against by the quality of interpersonal relationships in families. It is a trust-based, emotion focused model that aims to repair interpersonal ruptures and rebuild an emotionally protective, secure-based, parent-child relationship. Teenagers may experience depression resulting from the attachment ruptures themselves or from their inability to turn to the family for support in the face of trauma outside the home. The aim of ABFT is to strengthen or repair parent-child attachment bonds and improve family communication. As the normative secure base is restored, parents become a resource to help their child cope with stress, experience competency, and explore autonomy. I believe it should be integrated into the practice of all children’s social workers. If you’d like to learn more you can buy the latest book, Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Depressed Adolescents, here. I've written a couple of posts recently about Protecting Young Children Online and Protecting Big Kids Online. I was thrilled at how many times they were viewed and shared (Thank you!) and I hope they have helped you to feel more confident in safeguarding your children in the digital age. Since I last posted I've found the new Fire HD Kids Edition. It has some great easy-to-use parental controls where you're able to manage usage limits, content access and educational goals, plus there's a 2 year worry free guarantee! It looks fab! Children’s apps and websites were in the news on privacy grounds earlier this week, after the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) announced a review of how these services collect data on their young users. It will form part of an international project, coordinated by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, and will look at 50 websites and apps, particularly what information they collect from children, how that is explained, and what parental permission is sought. The websites and apps will include those specifically targeted at children, as well as those frequently used by them. So how can parents decide which sites, apps and games are appropriate? Today I was emailed about the NSPCC's updated Net Aware guide which helps parents to understand what their children are doing online and hopefully maintain open channels of communication. It's a huge database providing information on sites, apps and games. It tells you what it is, why kids like it and provides an age rating to help parents judge whether it's appropriate for their child. After having a look through the site I realised that I probably haven't heard of half of them before.  Research by the NSPCC earlier this year found that many parents have gaps in their online knowledge and don't talk about the right issues with their children. For example, Tinder, Facebook Messenger, Yik Yak and Snapchat were all rated as risky by children, with the main worry being talking to strangers. However, for the same sites the majority of parents did not recognise that the sites could enable adults to contact children. Although eight out of ten parents told the NSPCC that they knew what to say to their child to keep them safe online, only 28% had actually mentioned privacy settings to them and just 20% discussed location settings. One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication. Here are my top tips:

Take a look at the NSPCC guide and let me know what you think. I was overwhelmed at the positive response I got for my earlier post about Protecting Young Children Online (Thank you for sharing!) so as promised I am following up with one for older children in Key stage 2. The tips below should be used in addition to the security measures outlined last time. Of course, you might want to give them access to a greater range of websites now that they are older; however, you should still ensure that they are age appropriate. Technology and the internet has changed a lot since we were kids and keeping up to date can be a challenge. Many parents feel overwhelmed as their children’s technical skills seem to far exceed their own. However, children and young people still need support and guidance when it comes to managing their lives online if they are to use the internet positively and safely. There are a number of books and online resources available to increase your technical knowledge and skills. If you aren't that confident online or with electronic devices it might be worth brushing up now before the kids really surpass us in their adolescent years. Is your child safe online? A Parents Guide to the internet, facebook, mobile phones & other new media is a great starting point. It covers all forms of new media - iPhones, apps, iPads, twitter, gaming online - as well as social networking sites. If you want to learn more of the techie stuff behind maintaining personal privacy Internet Privacy For Dummies is a really accessible quick reference guide. Topics include securing a PC and Internet connection, knowing the risks of releasing personal information, cutting back on spam and other e–mail nuisances, and dealing with personal privacy away from the computer. The UK Safer Internet Centre offers a Parents' Guide to Technology. It introduces some of the most popular devices, highlighting the safety tools available and empowering parents with the knowledge they need to support their children to use these technologies safely and responsibly. The NSPCC and NetAware have also created a brilliant resource detailing sites, apps and games that they have reviewed. It's a huge database telling you what they are, why kids like them, and it gives an age rating to help you to judge whether it's appropriate for your child. Anyway, back to protecting your big kids... One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication.

It’s never too early or late to start talking to your child about staying safe online. There are a number of great resources available for parents and professionals to access and download. On my earlier post I showed you Smartie the Penguin by ChildNet. For children in key stage 2 there’s The Adventures of Kara, Winston and the SMART Crew. It’s a cartoon and each of the 5 chapters illustrates a different e-safety SMART rule.  is for keeping safe. Be careful what personal information you give out to people you don’t know  is for meeting. Be careful when meeting up with people you’ve online chatted to online.  is for accepting. Be careful when accepting attachments and information from people you don’t know they may contain upsetting messages or viruses.  is for reliable. Always check information is from someone reliable and remember some people may not be who they say they are.  is for tell. Always tell a trusted adult if something or someone online is making you worried or upset. You can watch the full movie online or download it to a device for later. For children at the older end of this age group, CBBC has an online comedy drama called Dixi. Dixi both encourages children to enjoy the creativity of the internet while also getting them to think about the potential dangers of social networking, from online privacy and safety settings, to the real-world consequences of cyber bullying. Cheryl Taylor, Controller of CBBC, says: “It’s important to raise awareness about safety online and Dixi does this in an engaging, educational and entertaining way”. There are also games that complement the drama for children to access through their website. You could also sit down together to watch the film below by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre. It’s called 'Jigsaw' and is suitable for this age group. It helps children to understand what constitutes personal information and enables children to understand that they need to be just as protective of their personal information online, as they are in the real world. It also directs them where to go and what to do if they are worried about any of the issues covered. It could be a great conversation starter and open up the channels of communication. I hope that you find this helpful. It can be a little intimidating when our children venture into the virtual world but with support and boundaries they will have have access to a resource with huge educational and social value. I'll post again soon with tips for supporting Teenagers / Young People in the digital age. Please follow me on facebook so that you don't miss it!

A friend asked me about e-safety today. She was concerned after finding her child on an inappropriate website and panicked. Her initial reaction was to revoke all on-line privileges as she did not feel confident in her ability to manage the situation. This is a natural reaction. We often want to remove our children from all situations which might cause them harm but in this day and age, it isn't particularly realistic. Children need to learn how to use computers and the internet. It will play a huge part in their lives growing up and should be supported if they are to enjoy and achieve, make a positive contribution and achieve economic well-being. So, here are my top tips for protecting young children (Foundation and Key Stage 1) whilst on-line. I will write a separate post for older children at a later date.

It's never too early to start talking to your child above staying safe on-line. There are a number of great resources available for parents and professionals to download. One of my current favourites is Smartie the Penguin by ChildNet International. You can download the story from the tools section of this website along with prompts for exploring the themes raised. It is a great way of introducing the boundaries we highlighted earlier in a child centred way.

The story follows Smartie the Penguin as he learns what to do when pop ups appear, when he finds himself on an inappropriate webpage and when he receives a message from a stranger. There are also a number of books that you can share with children to explain the importance of internet safety. Chicken Clicking is described as Little Red Riding Hood for the iPad generation; this is the perfect book for teaching children how to stay safe online. Penguinpig teaches children about stranger danger online. When a little girl reads about a penguinpig on the Internet, she decides that she must go and find one. Not telling her parents, she sets off to the zoo and carefully follows the instructions from the website. Penguinpig has received acclaim from children's authors Andrew Cope and Ian Whybrow, and has been recommended for families and schools by Claude Littner (BBC1's The Apprentice). The Internet is Like a Puddle by Big Hug Books attends to the wonderful aspects of electronic communication as well as gently discusses some of the possible pitfalls of sharing, chatting and using data. The Big Hug books grew out of letters sent to children and their families after their psychology sessions. Each book has its origins in a real need for a real child with a real problem and offers real strategies from a real psychologist. The heart-felt illustrations and simple words aim to simplify tricky situations and soothe strong emotions. The books aim to give children, and the people who care for them, a way to talk about problems. Digiduck's Big Decision is an illustrated children's book that tells the story of Digiduck and his friends, to help children understand how to be good friends to others on the internet. Designed for children age 3-7 years (Foundation stage and KS1) this book is very accessible for this audience. I hope that you find this helpful. It can be a little intimidating when our children venture into the virtual world but with support and boundaries they will have have access to a resource with huge educational and social value. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|