|

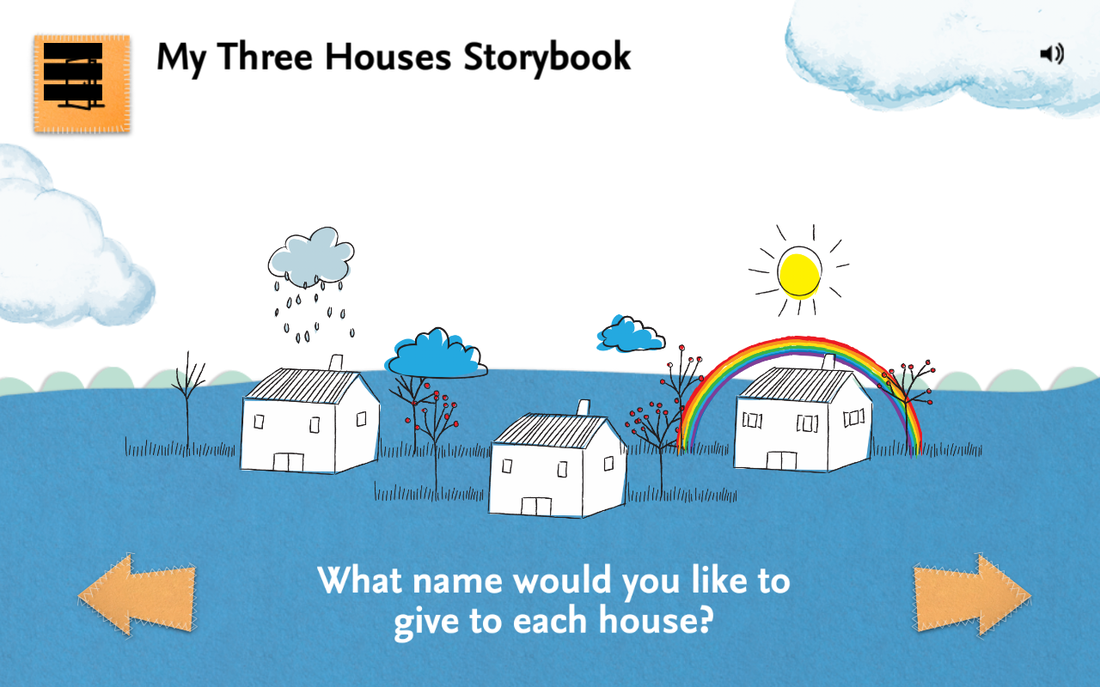

In 2010/11 Professor Eileen Munro reviewed the English children’s services system and found organizations and workers had become over-bureaucratized and compliance driven at the expense of direct work with families, parents and children. Following the recommendations of the Munro review, the UK government launched a Children’s Services Innovations programme which, amongst other things, has financed the development of a new app for social workers to use in their practice with children and families. Developed in Western Australia and designed with children’s services practitioners in UK, USA and Australia, the My Three Houses App offers a tool that taps into children’s love of all things iPad and encourages them to speak about what is happening in their life. The three houses tool was first conceived in New Zealand in 2003 and since then has been used by social workers all over the globe to place the voice of the child at the centre of child protection assessment and planning. I've blogged about using the analogue version here. This app brings the tool into the digital realm. There's video... Interactive animation... and a drawing pad for children.

0 Comments

The All Party Parliamentary Group on Runaway and Missing Children and Adults is inviting interested individuals and groups to submit written evidence to its current inquiry into how the police, children's services, schools and other professionals safeguard children who are categorised as 'absent' from home or care or education. The inquiry is intended to examine how the introduction of the ‘missing’ and ‘absent’ categories has affected the safeguarding response to children who run away.

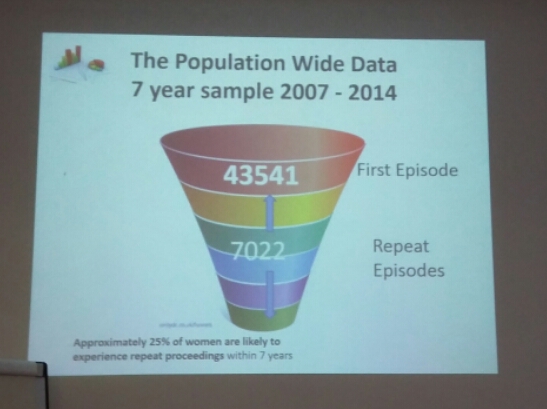

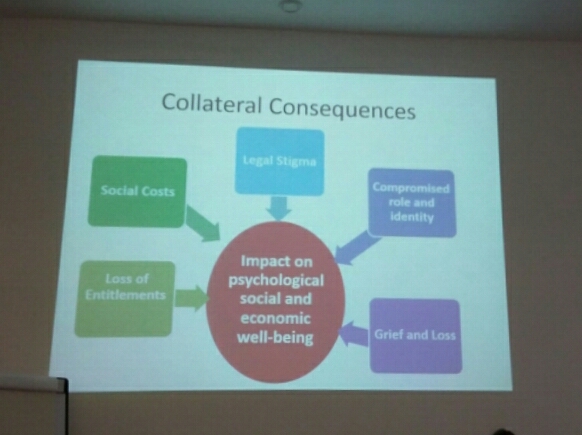

Ann Coffey MP raised concerns about the new absent category in her report published in October 2014 ‘Real Voices – Child Sexual Exploitation Greater Manchester’. The deadline for submissions of written evidence is Friday, 22 January 2016. You can find out more information here. Further reading: Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care. Report from the Joint Inquiry into children who go missing from care (June 2012). Yesterday I attended ‘Parents’ Voices and their Experiences of Services’ at Friends Meeting House in Manchester. It was an opportunity to examine priorities for system, policy and practice change, drawing upon findings from research and was a very valuable day for reflective practice. The event began with a short introduction by Safeguarding Survivor who chaired the conference with great confidence and professionalism. I know she was nervous but you couldn't tell and she did a brilliant job. If you aren't aware of her story, I recommend you read her blog. It offers great insight into the child protection system from a parents’ perspective and provides excellent advice for others whose children have been identified as ‘at risk’. Her work has been praised for its balance and value by Sir James Munby and you will soon be able to read more of her case after the court granted Louise Tickle (a freelance journalist) permission to publish details in a broadsheet newspaper. You can read the judgement at Family Law.  Siobhann and three mothers from The Mothers Apart project (Women Centre) Kirklees spoke about their book In Our Hearts. It presents open and honest accounts of initial separation, court proceedings, relationships with services, of mothers who have been able to have children returned to their care or contact increased, mothers who have no current contact at all and those for whom contact remains limited. It offers itself up as an aid and guide to learning for parents, families and professionals working in pursuit of child protection. As a result of co-production learning Mothers Apart have developed women centred working that recognises people as assets. Whilst every woman is different they have found that there are a number of common themes and, consequently, much of their work is about power. Sean Haresnape (Principal Social Work Advisor) from Family Rights Group outlined a Parents Charter being developed in collaboration with parents and professionals, that sets out expectations of how services should engage with parents, whose children are subject to statutory interventions; and we heard from Declan, a father and care leaver who had his daughter placed with him following care proceedings. Prof. Karen Broadhurst (Lancaster University) and Claire Mason (ISW & Lancaster University) presented preliminary findings from their 2 year study of birth mothers, their partners and children, within recurrent care proceedings under s.31 of the Children Act in England. The project hopes to confirm the national scale and pattern of recurrent proceedings together with the characteristics and service histories of parents caught up in this cycle. Statistical methods have been used to quantify recurrence and examine the relationship between recurrence and key explanatory variables. This has been complemented by qualitative components that include in-depth interview work with birth mothers in five local authority areas and in-depth profiling of a subset of randomly selected case files. Through data mining they have found that 25% of women who have been through care proceedings will return within 7 years. Teenage motherhood is associated with a significant number of repeat care proceedings and Prof. Broadhurst questions whether the family court is the most appropriate setting for dealing with teenage parents. Another facet of their research looks at the collateral consequences of care proceedings and asks who, once a court case has concluded, is there to support parents with the psychological, social and economic consequences of losing a child. Whilst the child and adopters/foster carers remain supported for a time by Social Workers and other services, there are no statutory support available to parents. This short-sighted approach demonstrates a lack of understanding of the collateral consequences and their cumulative impact which can drive women in to unhealthy relationships and successive pregnancies. In subsequent cases Local Authorities and Courts have been found to act more swiftly and are more likely to remove closer to birth, with adoption being the most likely outcome, compounding the cycle.

Similar concerns were raised last week by Sir James Munby when I attended the annual Family Justice Council debate in London. He said that it was “not fair on subsequent children that post adoption support isn't provided to birth parents” and “there is some substance to the question whether resources are adequately balanced between support for adoption and support for families”. Finally, Prof. Kate Morris (Sheffield University) outlined the empirical research she and Prof. Brid Featherstone (University of Huddersfield) are conducting as part of Your Family Your Voice – an alliance of families and practitioners working to transform the system. Their work, looking at family experiences of multiple service use, highlights the profound difficulty families often find navigating their way through services. At the end of the presentations we were asked to reflect upon what we had heard and identify what changes could be made to make the system a more humane one and minimise trauma for parents, children, their families – and also for practitioners. I invite you to do the same and participate in the research here. Family, What Family? Unpicking the tangled knot of human rights in child protection practice1/7/2015 Last night I attended a seminar hosted by BASW and the University of Wolverhampton. It was called 'Family, What Family? Unpicking the tangled knot of human rights in child protection practice' and delivered by Allan Norman. You might have heard of Allan before. He qualified as a social worker in 1990, and as a solicitor in 2000. He specialises in the law relating to the practice of social work, representing both social workers and service users through his own legal and independent social work practice Celtic Knot. He's also an Associate Lecturer at the University of Birmingham and now works as BASW’s lead on Policy, Ethics and Human Rights and International matters.

The seminar was fascinating and I came away with a greater clarity regarding the impact child protection processes have on both the rights of the child and family. Allan started by saying that Social Work as an international profession is fundamentally about human rights. The International Federation of Social Workers say just that in the Global Definition of Social Work. But for those working in areas of safeguarding that commitment to both positive and negative rights becomes complicated. We also find that absolute rights always trump qualified rights. So, a child's absolute right under article 3 ("No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment") trumps the parents qualified right under article 8 ("Right to respect for private and family life"). Allen questioned whether low level neglect was sufficient for article 3 to be engaged. No doubt the impact of austerity and the increasing threshold for support and preventative services will muddy these waters even more. Earlier today I read that all four UK Children’s Commissioners have called on the UK Government to stop making cuts to benefits and welfare reforms in order to protect children from the impact of its austerity measures. Tam Baillie, Commissioner for Children and Young People Scotland, said "For one of the richest countries in the world, this is a policy of choice and it is a disgrace. It is avoidable and unacceptable." It is right that children are safeguarded from significant harm, but removing them from their family is a hugely draconian step which should be reserved as an absolute last resort. How many families might still be together if the government prioritised funding for welfare, support and preventative services? In individual cases it may be that there are no other support options; but as a society do we not have a moral duty to make that support available? As a society are we failing in our duty to meet the positive rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? It's food for thought... Allan has written prolifically on the subject of Human Rights and child protection. If you're interested in reading more, take a look at some of these: ‘Working Together 2013 ignores human rights and we must act on this’ Disappearing act Dealing with the inconvenient human rights of others You might also like some of these (Not by Allan!): We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures I Have the Right to Be a Child Ethics and Values in Social Work (Practical Social Work Series) BASW Human Rights Policy (Sort of by Allan!)

Childhood is a time of rapid change. Some of these changes are obvious, such as height gain, language ability and physical dexterity. Others are less obvious, such as how children make sense of the information in their environment. To understand the rapid changes of childhood, children’s abilities are often judged against developmental milestones, such as acquiring language (babbling, talking), cognition (thinking, reasoning, problem solving), motor coordination (crawling, walking) and social skills (identity, friendships, attachments). But how does digital technology influence the acquisition of these important skills? Does technology hinder a child’s physical, social and cognitive development, or does it provide exciting opportunities for learning?

The entertainment and interactivity of tablets and smartphones has made them attractive to children. Touch-screen interfaces mean that digital technologies are now accessible for children at a very young age. But do children find digital technologies exciting for reasons beyond simple entertainment? The amount of digital technology available to my young daughters is massively different to that in my own childhood. As both a parent and a Social Worker, I've found it difficult to make sense of media reports and research findings in this controversial area. Is technology beneficial or detrimental to child development? Does screen time lead to increased distractibility, obesity and loneliness? Or does it offer opportunities for autonomy and experimentation beyond anything imagined when I was a young child? As the generation gap widens between adults and children’s' understanding of new technologies, how will we protect them from the risks while allowing them to benefit from the opportunities new technologies offer? In 2014 both Ofcom and the NSPCC (Jütte et al.) found that one in three children owned their own tablet. Figures published by the NSPCC also show smartphone ownership increasing with age (20 per cent of 8–11-year-olds and 65 per cent of 12–15-year-olds). These profound changes are reshaping children’s digital environment. The recent EU Kids Online Network project, called Zero to Eight, illustrates just how pervasive technology is becoming for younger children. The project report identified a significant increase over the previous five years of children under nine years old using the internet (Holloway et al., 2013). In particular it noted a growing trend for very young children (pre-schoolers) to use tablets and smartphones to access the internet:

Whilst children are now going online at a younger age, their ‘lack of technical, critical and social skills may pose [a greater] risk’ (Livingstone et al., 2011). The challenge for parents is how best to manage the risks alongside the benefits. I’ll get back to this later…

Children and Digital Technologies Children are often very engaged by digital technology. But why is it so compelling for young children to spend so much time interacting with their digital world? Firstly, technology is fun. Child-centred technology in particular is especially designed to be as entertaining and captivating as possible. Similarly, a big attraction of technology for children is that they see their parents and peers using it, and a major part of childhood is ‘modelling’ the behaviour of those around them, particularly parents: that is, children learn from observing and imitating others around them. Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory (SDT) seems particularly relevant to untangling the reasons behind young children’s fascination with the digital world. According to SDT, there are two overarching types of motivation, ‘intrinsic motivation’ and ‘extrinsic motivation’. The former refers to doing an activity for its own sake because it is enjoyable and this is thought to lead to persistence, good performance and overall satisfaction in carrying out activities. Ryan and Deci outline three basic psychological needs associated with intrinsic motivation that can be applied to children’s use of technology:

Although each of these three basic psychological needs may not be met for every child, the self-determination theory offers a good psychological basis for understanding children’s intrinsic motivation in using technology. According to one study, children are currently spending more time with technology than they do in school or with their families. Similarly, children as young as 2, 3 and 4 are playing with their parents’ phones or tablet devices; and some psychologists argue that this has an enormous impact on their brain development, as well as on their social, emotional and cognitive skills. This raises an important question: in this 24/7 digital world, should parents be setting new rules for their children’s engagement with technology? Should we be promoting new parenting classes for the modern age? Generational Divide The idea of a generational divide between children and adults has been a popular topic among psychologists and sociologists. This has resulted in the use of labels such as the ‘digital native’, the ‘net generation’, the ‘Google generation’ or the ‘millenials’, each of which highlights the importance of new technologies in defining the lives of young people. The most contentious term is the ‘digital native’. The term first appeared in an article by Marc Prensky to describe those children who spend much of their lives ‘online’, constantly ‘switched on’. It represents ‘native speakers’ who are ‘fluent in the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet’. There is a distinction between ‘digital natives’, who are those generally born after the 1980s and are technologically adept and comfortable in a world of technology, and ‘digital immigrants’, who are generally born before the 1980s and are fearful or less confident in using technology. To justify his claims Prensky draws on the widely held theory of neuroplasticity. This means that our brains are highly flexible and subject to change throughout life. The different neural connections in the brain change and evolve throughout childhood in response to the environment. It is claimed that young children’s brains now are developing differently to the way adults’ brains have developed, as children are growing up surrounded by new technologies. This topic of neuroplasticity is something that I have also covered in Risk, Resilience and Adoption. Safeguarding Many parents, teachers and Social Workers have legitimate reasons to worry about children’s engagement with the digital world. We know that children are likely to run risks if they access the internet unsupervised, or stay online for long periods of unbroken time. Examples of the apparent risks appear in the work of Howard-Jones, who analysed current research in neuroscience and psychology. He states that the developing brain can be susceptible to environmental influence, and digital technology opens it to risks including:

You can also find research into internet addiction, aggressive game-playing, grooming and bullying, which have also been linked to children’s exposure to the digital world. Social Media can also present problematic situations for adopted children, and those in foster placements or subject to child protection plans. Even the Pope waded in on the debate earlier this month, warning parents not to let children use computers in their bedrooms because of the 'dirty content' on the internet. Whether you are a digital optimist or pessimist, it’s obvious that while technology brings about opportunities, it also has associated risks. This has led to some professionals arguing that parents should limit young children’s use of, and exposure to, new digital technologies. But is this really the answer? Is simply restricting children’s access actually the best way to ensure their safety? Restricting access to technology may also restrict opportunities for children to develop resilience against future harm and I would argue that simply restricting access or removing technology from children’s lives seems inappropriate (except as a short term measure in cases where technology is presenting a significant risk of harm to the child). Perhaps we need to review parenting methods so we ensure sufficient levels of support for children growing up in this highly digital modern world. If we look at self-determination theory, the idea of giving children autonomy and choice to make appropriate decisions about their own digital world could be the answer. According to some, we need to trust in the maturity and judgement of children. We have to be able to trust their social skills in successfully negotiating these new ways of behaving and successfully managing or avoiding risks (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). It is important to recognise that children’s perceptions of problematic online situations may differ greatly from those of adults. Because of the different perceptions of adults and young people, and the lack of a neat distinction between positive and negative experiences online, many professionals opt to avoid the term ‘risk’, and prefer to talk about ‘problematic situations’. Research by Vandoninck and colleagues, based within the UK, tackles the idea of giving children autonomy to make their own choices. Awareness of online risks motivates children to concentrate on how to avoid problematic situations online, or prevent them from (re)occurring. This brings me to the concept of preventive measures – what children actually do or consider doing in order to avoid unpleasant or problematic situations online. Vandoninck and colleagues identified five main categories of measures discussed in the literature:

Perhaps the key focus of parents and professionals should be on helping children to acquire the knowledge and skills to moderate their own online behaviours; to develop resilience to risks and to become responsible digital citizens of the twenty-first century (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). For more information about safeguarding, take a look at my other posts on online safety and follow me on facebook and twitter. Today Edward Timpson, Children and Families Minister, addressed the NSPCC conference about how social work reform and innovation can help better protect vulnerable children. He became a Member of Parliament in 2008 after winning a by-election in the constituency of Crewe and Nantwich. In September 2012, he was appointed as a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Education, and following the 2015 general election, he was promoted to Minister of State for Children and Families.

You can see the whole speech here, but I've summarised/quoted the main points below. He started his speech with a little self-deprecation, saying how thrilled and surprised he was to be back in office, before drawing attention to his own upbringing, in a household with adopted and fostered siblings, and his work with children in care. He says he believes “the protection of vulnerable children… [is] the most profound responsibility we have as a society". He said that during the last parliament he had worked to “strengthen the child protection system… with major reforms to social worker recruitment and assessment”. Also “the first independent children’s trust in Doncaster”, he claimed, are “freeing up local authorities so that they can set up new models of delivery”. Child sexual abuse and NSPCC report Referring to investigations in Rotherham, Rochdale and Oxford he said: “we’ve been able to shine a light on a police and social care system set up to protect children, but that all too often turned them away, leaving them in the hands of callous abusers”. He also said that “the Prime Minister has appointed Karen Bradley as a minister in the Home Office to tackle [CSE] alongside [him] - recognition that child sexual abuse is about child protection... but also about prosecution too”. Centre of Expertise Timpson reported that a “new Centre of Expertise” will try “to understand what works when it comes to tackling and preventing child sexual abuse”. In addition, he acknowledged “that while CSE is dominating the media, we must not lose sight of neglect”. That’s why, he said, they’re “looking at having a campaign to encourage the public to report all forms of child abuse and neglect”. Social work reform “At the heart of good child protection is, of course, good social workers”. He said that “the introduction of a new assessment and accreditation system for children’s social workers” will offer “a rigorous means of assuring the public that social workers…have the knowledge and skills needed to do the job”. His department will also continue to support “projects to bring the brightest and best into social work through Step Up to Social Work and Frontline”. Innovation programme Timpson said that he was “especially keen to see much closer working between the voluntary sector and local authorities - something the Children’s Social Care Innovation programme is encouraging and seeing take root.” There’s a “£1.2 million initiative with SCIE - The Social Care Institute for Excellence - that aims to help us learn better from serious case reviews (SCRs) and improve their quality, and which includes a pilot to improve how SCRs are commissioned”. There’s also a “£1 million funding for the NSPCC to introduce the New Orleans intervention model in south London - which aims to improve services for children under 5 who are in foster care because of maltreatment by promoting joint commissioning across children’s social work and CAMHS teams.” Character and resilience Timpson’s “brief has been extended to include character and resilience”, placing “a greater emphasis on helping children… develop the qualities and life skills that will give them a strong foundation for social life”. He told the audience of social care professionals that “there’s a need to get better and smarter about how we equip our sons and daughters with the attributes they need to find their feet today and truly flourish.” He concluded his speech by asserting that he is a “pragmatist and simply [wants] to do what’s best by and for children, wherever they are and whatever their circumstances.” Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

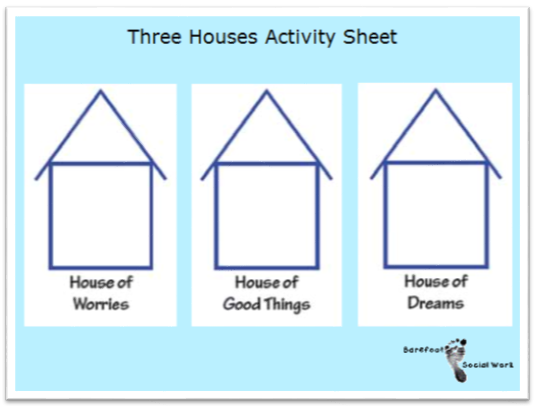

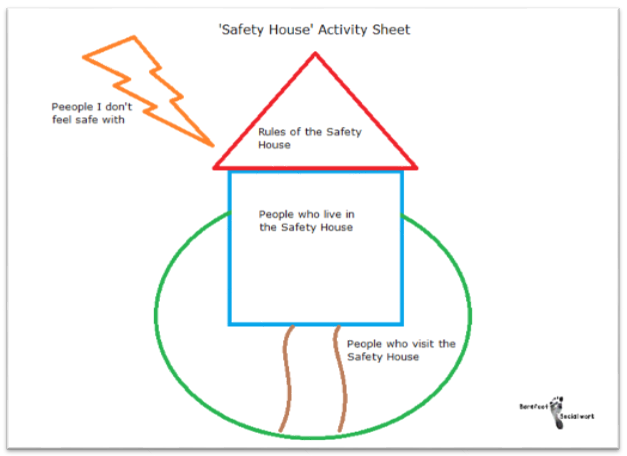

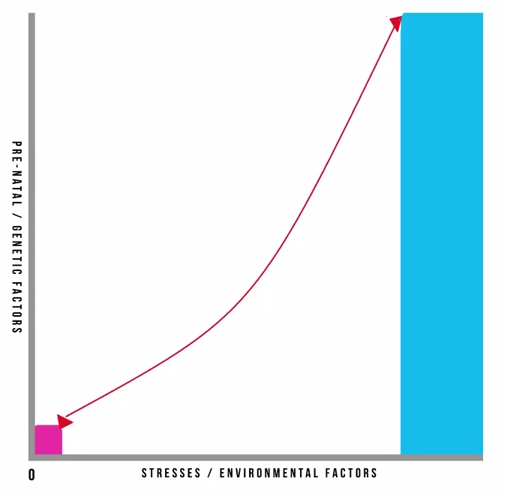

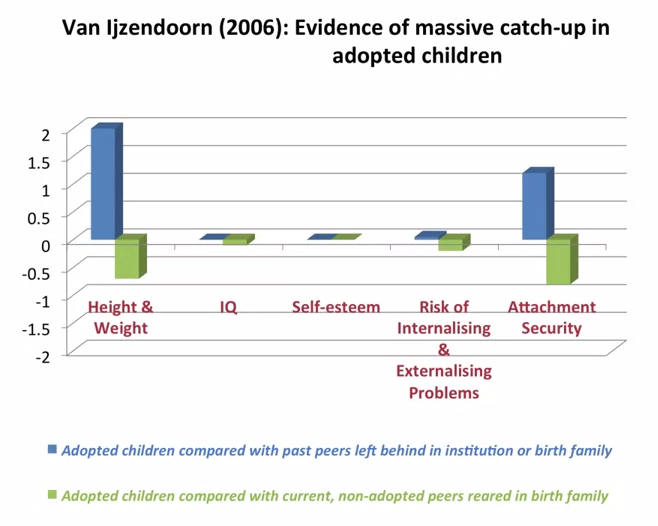

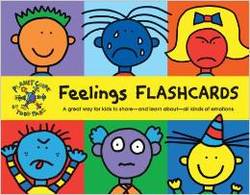

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.  The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred” system was for social workers to have the time and the skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. NICE has also recommended that professionals take greater steps to actively involve children and young people in the process of entering care, changing placement, or returning home and a series of intervention tools should be considered to help guide decisions on interventions for children and young people. What this means is that there is a general consensus that there should be a greater focus on direct work in professional practice. Direct work with children is a complex skill to master but the techniques can be relatively simple. Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective in the past. In most cases all you need is pen, paper and time. The 'Three Houses' technique was created by Nicki Weld and Maggie Greening in New Zealand (Weld 2008, cited by Turnell 2012) and is mentioned in the Munro review. It helps a child or family think about and discuss risks, strengths, and hopes. It is usually most effective with older children or with families where you are finding it difficult to devise an effective intervention plan and can be used with individuals or a group. Taking three diagrams of houses in a row, Social Workers explore the three key assessment questions: 1) What are we worried about, 2) What’s working well and 3) What needs to happen/how would things look in a perfect world. Start by presenting the three blank houses to the child or they could draw their own. Beginning with the ‘House of Good Things’, the child is asked what the best things are about living in the house and questioning is directed around positive things that the child enjoys doing there. After this stage you should progress to discuss the ‘House of Worries’ and find out if there are things that worry the child in the house or things that they don’t like. Finally the ‘House of Dreams’ covers an exploration of thoughts and ideas the child has about how the house would be if it was just the way they wanted it to be. A description is built up detailing who would be present and what types of behaviours would occur. The ‘Safety House’ tool was developed by Sonja Parker. It helps to represent and communicate how safe a child feels in their own home and what could be done to improve things. It can be used with children who are not currently living with parents in order to plan for reunification. Progress can also be assessed by changes in the safety house drawing and can be a key tool in the assessment of risk and safety planning. Start with a picture of a house with a roof, path and garden. The house and garden are divided into sections and the child can describe who they would like to live with them, who can visit and stay over and who is not allowed to come into the house. Safety rules are devised and put into the roof of the house and details of what happens in the house and what people do can be discussed. The house can also be utilised as a readiness scale by using the path as an indicator of how ready they are to return home.  The faces technique involves asking the child to pick from a range of different facial expressions and assigning them to members of their family. It is a useful method for discovering how a child perceives their family and is likely to appeal to younger children or those at an earlier stage of development. After explaining to the child that you want to know more about their family, show them some pictures of different facial expressions, making sure they understand each expression and the emotion it relates to. You could draw them yourself or use a professional set. I recommend the Todd Parr Feelings Flash Cards which are really attractive and accessible for young children. They’re also thick, sturdy and, most importantly, durable. For more developed children, you can select a wide range of expressions; for those at earlier stages of development, you might want to just use two or three (ie happy, sad and angry). There are many other activities that are effective in direct work with children and young people. I will try to write more posts soon. Follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss them! In the meantime, you might like to take a look at Audrey Tate’s book, Direct Work with Vulnerable Children. It’s primarily a set of playful activities to create opportunities to engage children. Through these activities children are enabled to tell their stories and provide Social Workers with assessment and support opportunities. Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

I was overwhelmed at the positive response I got for my earlier post about Protecting Young Children Online (Thank you for sharing!) so as promised I am following up with one for older children in Key stage 2. The tips below should be used in addition to the security measures outlined last time. Of course, you might want to give them access to a greater range of websites now that they are older; however, you should still ensure that they are age appropriate. Technology and the internet has changed a lot since we were kids and keeping up to date can be a challenge. Many parents feel overwhelmed as their children’s technical skills seem to far exceed their own. However, children and young people still need support and guidance when it comes to managing their lives online if they are to use the internet positively and safely. There are a number of books and online resources available to increase your technical knowledge and skills. If you aren't that confident online or with electronic devices it might be worth brushing up now before the kids really surpass us in their adolescent years. Is your child safe online? A Parents Guide to the internet, facebook, mobile phones & other new media is a great starting point. It covers all forms of new media - iPhones, apps, iPads, twitter, gaming online - as well as social networking sites. If you want to learn more of the techie stuff behind maintaining personal privacy Internet Privacy For Dummies is a really accessible quick reference guide. Topics include securing a PC and Internet connection, knowing the risks of releasing personal information, cutting back on spam and other e–mail nuisances, and dealing with personal privacy away from the computer. The UK Safer Internet Centre offers a Parents' Guide to Technology. It introduces some of the most popular devices, highlighting the safety tools available and empowering parents with the knowledge they need to support their children to use these technologies safely and responsibly. The NSPCC and NetAware have also created a brilliant resource detailing sites, apps and games that they have reviewed. It's a huge database telling you what they are, why kids like them, and it gives an age rating to help you to judge whether it's appropriate for your child. Anyway, back to protecting your big kids... One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication.

It’s never too early or late to start talking to your child about staying safe online. There are a number of great resources available for parents and professionals to access and download. On my earlier post I showed you Smartie the Penguin by ChildNet. For children in key stage 2 there’s The Adventures of Kara, Winston and the SMART Crew. It’s a cartoon and each of the 5 chapters illustrates a different e-safety SMART rule.  is for keeping safe. Be careful what personal information you give out to people you don’t know  is for meeting. Be careful when meeting up with people you’ve online chatted to online.  is for accepting. Be careful when accepting attachments and information from people you don’t know they may contain upsetting messages or viruses.  is for reliable. Always check information is from someone reliable and remember some people may not be who they say they are.  is for tell. Always tell a trusted adult if something or someone online is making you worried or upset. You can watch the full movie online or download it to a device for later. For children at the older end of this age group, CBBC has an online comedy drama called Dixi. Dixi both encourages children to enjoy the creativity of the internet while also getting them to think about the potential dangers of social networking, from online privacy and safety settings, to the real-world consequences of cyber bullying. Cheryl Taylor, Controller of CBBC, says: “It’s important to raise awareness about safety online and Dixi does this in an engaging, educational and entertaining way”. There are also games that complement the drama for children to access through their website. You could also sit down together to watch the film below by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre. It’s called 'Jigsaw' and is suitable for this age group. It helps children to understand what constitutes personal information and enables children to understand that they need to be just as protective of their personal information online, as they are in the real world. It also directs them where to go and what to do if they are worried about any of the issues covered. It could be a great conversation starter and open up the channels of communication. I hope that you find this helpful. It can be a little intimidating when our children venture into the virtual world but with support and boundaries they will have have access to a resource with huge educational and social value. I'll post again soon with tips for supporting Teenagers / Young People in the digital age. Please follow me on facebook so that you don't miss it!

Political Rhetoric: Is Social Work on the political agenda in the run up to the general election?17/4/2015  Community Care reported on Wednesday that UKIP would seek wholesale reform of Britain's "clearly failing" child protection services, if elected. If I may overlook the fact that this is from UKIP for a second; if this policy was coming from any of the political parties I would be very interested in hearing more. Highly skilled and able practitioners are working in a very challenging environment with many systematic failures. If any party was to take an open and unbiased review of child protection services I would be very pleased because they would see what many of us have known for years. However, I am rather sceptical about any of their motives. In my experience politicians are too quick to scapegoat practitioners rather than look at the impossible system within which they are expected to practice safely and invest the necessary capital; because that is what is needed - INVESTMENT. When politicians refer to Child Protection Services what they are actually talking about is Children's Social Care. The problem with this choice of rhetoric is that it leads the majority of voters to believe it is not a service that they will ever need and therefore, whilst they may be interested and concerned, they would not prioritise spending in this area. This is a false dichotomy. Children's Social Care encompassed a whole host of services for a diverse demographic of children and young people. We are not just talking about front-line Social Workers but also the preventative services that are bearing the brunt of cuts; support and care for looked after children; services and respite for families of children with additional needs. Social Workers do not only work with 'troubled families' but also families experiencing crisis whatever their background. Leading the often complicated array of professionals and services are Social Workers. It is when Social Workers are overstretched and unable to do the job they love that the system falls apart and children are put at risk. Serious Case Reviews often cite poor multi-agency working - Social Workers, when sufficiently resourced, are the glue that holds it all together and should be valued for the job they do. I have worked with an incredibly mixed demographic of clients in my time. Some would have fitted the governments definition of a 'troubled family' others would not. My role has involved safeguarding children from physical, sexual, and emotional harm. It has also included working with parents who need support and assistance as a result of redundancy, homelessness, illness and disability. One family in particular springs to mind as I write this; they were a young professional family who had fallen on hard times as a result of redundancy. Dad had lost his job and, as result of the economic downturn, was finding it difficult to bridge the gap. He was extremely conscientious, hard working and proud. He found it very difficult asking for help but when he was unable to pay the rent and they lost their home, without any extended family to offer assistance, he turned to Children's Services to help him, his wife and their two young daughters. It was only a month until he found employment again but I am sure he would say that we offered him a much needed lifeline. This was not his fault and I am sure a year or two earlier he would not have envisaged a time when he and his family would have ever needed the help of a Social Worker. This is my point: you never know when you will fall on hard times; this is why Social Care should be on the political agenda; and why voters should be interested in what party manifestos have to say about it. So, lets take a look at what the main parties have to say in their manifesto's. Labour would avoid "extreme" social care cuts and continue to fund the Frontline fast track training scheme for Children's Social Work according to their manifesto. They would also:

The Conservatives would create regional adoption agencies that work across local authority boundaries, the party manifesto has pledged. "Far-reaching powers" over social care would also be devolved to large cities that opt to having an elected mayor, like Greater Manchester. Their party manifesto also said they would:

The Liberal Democrats have pledged to "radically transform mental health services" if they are elected to government. Their manifesto states that a Liberal Democrat government would build on the work of the coalition to establish parity between physical and mental health services. They also say they would:

The Greens have pledged free social care and health care for all older people at a cost of "around £8bn a year" and an end to "failed" austerity. Their manifesto also promises:

As mentioned earlier, UKIP would seek wholesale reform of the "clearly failing" child protection services in Britain, if it were to win the next general election. They would hold an open review of all childcare and child protection services, with a view to reforming the system. The cited concerns over "misplaced sensitivity to issues of race and religion", "forced adoptions" and professionals "letting serious cases of abuse and maltreatment slip through the net". In their manifesto UKIP said that they would:

The Greens win for me but as we don't have a visible candidate in my area this is a mute point. What party impresses you the most? Why? I hope that the next government values Children's Social Care enough to invest in it. I hope that they realise it is not only a bad workman that blames his tools. It is impossible for Social Workers to produce good outcomes 100% of the time when they have sky high caseloads and dwindling preventative services. Cafcass have just published their third survey of Guardians’ views regarding care applications (s31 Children Act 1989) made by local authorities.

The aim was to gauge the views of Guardians in relation to care applications received by Cafcass during the period 11 – 29 November 2013, specifically in relation to:

Key findings from the research include:

This research will come as welcome affirmation to Social Workers in the sector whom seldom see their dedicated work with children and families recognised in the public arena. However, it is disappointing that I was unable to find one news article related to the report during a quick Google search. News agencies are quick to pick up on damning findings from serious case reviews but are not so interested to learn that on the whole Social Workers do a very good job safeguarding and protecting vulnerable children. If you would like to read the research in full you can find it here. Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) is a way of talking with people about change that was first developed for the field of addictions but has broadened and become a favoured approach for use with a wide variety of populations in many different settings. It complements the strengths based approach that is gaining in popularity and engages clients as agents of change.

Typically, in child protection parents motivation for change is presumed to be static. They either possess it or lack it and there is very little the Social Worker can do to change this. Under these conditions the Social Worker becomes a punitive enforcer of court orders and agency rules and regulations and does little to promote change. Under the threat of punitive measures parents are asked to change or else. However, it is well documented that a confrontational counselling style limits effectiveness. Miller, Benefield and Tonnigan (1993) found that a directive-confrontational counselling style produced twice the resistance, and only half as many “positive” client behaviours as did a supportive, client-centred approach. The researchers concluded that the more staff confronted substance-involved clients, the more the clients drank at twelve-month follow up. Problems are compounded as a confrontational style not only pushes success away, but can actually make matters worse. By using Motivational Interviewing interactions become more change focussed and relationships between families and Social Worker become more collaborative. The technique should be used simultaneously with other protective measures to ensure that children are safeguarded from the risk of significant harm. I trained to use motivational interviewing whilst working with an offending and addiction service in 2007. I have since found the technique to be hugely beneficial when applied to work with children and families. If you would like to learn more, Motivational Interviewing in Social Work Practice is an excellent book providing an accessible introduction to MI with examples of how to integrate this evidence based method into direct practice. You can also find some useful MI tools on my website. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|