|

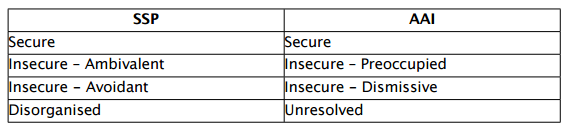

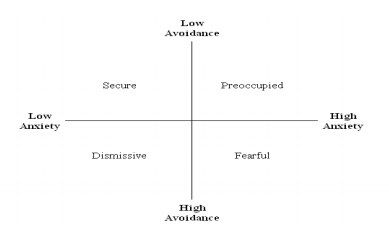

Yesterday I posted about the origins of attachment theory. Draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argue that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. My personal experience of the Social Work Masters was that attachment was covered but in a rather one dimensional manner without the necessary critical analysis. In recent years, some assumptions have been challenged and this post will look at three of the main debates in the theories of attachment. These debates are ongoing and you will have to judge for yourselves. Adult attachment styles are dictated by the mother-child relationship. This assumption rests on the principle of monotropy, but recent reconceptualisations of attachment suggest that attachment might be more significantly influenced by multiple caregivers and relationships. There are three possible models: Firstly, the Hierarchical model is the classic understanding of attachment theory, in which attachment is to a primary caregiver (the mother) and that this relationship is concordant with other attachment relationships, and mediates future relationships. This model derives from Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s research. Secondly, the Integrative model describes an alternative organisational structure in which the child integrates all of his/her attachment relationships into a single representation. In this model, by Van IJzendoorn et al. (1992) they suggest that all attachment relationships are equal and independent, and the quality of the combined relationships best predicts his/her developmental consequences. The entire extended network of attachments is a better predictor of attachment than family attachment style only. Thirdly, the Independent model states that each attachment relationship brings an independent representation with qualitative differences, domain and person specific. For example, the child’s relationship with peers is more likely to be determined by the maternal attachment, whilst social competence, efficacy and adjustment is more likely to be determined by paternal attachment. The evidence for this model is less well-established, but Crittenden’s Dynamic Maturational Model uses a version of this as its basis (more on that later). There is evidence, both for and against these models using cross-cultural studies, studies of attachment in adolescence, and inter-generational studies. It's probably too much to cover right now but I may cover it in another post at a later date. A categorical classification system is the most accurate way to describe attachment styles. The two most significant attachment measures are the Strange Situation Protocol, used with toddlers, and the Adult Attachment Interview. Both allocate individuals to one of four categories. If you’re interested in finding out more about your own attachment style you might like to look at this online version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale, a test of attachment style. The ECR was created in 1998 by Kelly Brennan, Catherine Clark and Philip Shaver. It groups people into four different categories on the basis of scores along two scales. The inventory consists of thirty six that must be rated on how characteristic they are of you. If you do complete the above questionnaire, you will be given a classification made on the basis of a dimensional conceptualisation of attachment, that looks like the one below. Fraley & Spieker (2003) have argued that this provides a more sensitive and ecologically valid assessment of individual attachment style. Finally, Patricia Crittenden has elaborated further by creating a model of attachment called the Dynamic Maturational Model. Crittenden’s model assumes multiple frames of reference and context-dependent responses, centred around a cluster of sub-categories. So, instead of the individual being categorised, the individual has a set of strategies, which can be matched to a range on this sphere. She adheres very strongly to an evolutionary framework. To see an overview of her theory, take a look at this YouTube video where she gives a presentation, titled "The development of protective attachment strategies across the lifespan", at the BPS DCP Annual Conference in 2012: Attachment style is set by 12-18 months

Bowlby’s original theory implied, partly by its focus on a single caregiver, that attachment style might be set quite early on, although he explicitly allowed for life events and circumstances to allow change. However, it was Ainsworth’s development of the Strange Situation Protocol that really reinforced the idea that attachment style is set by the time of primary individuation at or around 18 months. There is evidence to support this stability of attachment style, but it is not black and white. Different studies have found that:

So, attachment classification certainly has predictive power, but not 100%. In adoption studies (See my previous post on Risk, Resilience and Adoption), children adopted before 12 months of age are only slightly more likely to be insecurely attached than children raised in birth families, whilst children adopted after 12 months are at significantly higher risk of insecure attachment, and disorganised attachment specifically. There are many, many more debates around theories of attachment. Too many to cover in a short blog post. However, I hope this has given you a tiny introduction to current thinking around the topic. It is important that practitioners are aware of these issues so that they can assess for themselves how best to integrate them into practice. Unfortunately, I can't give you a definitive answer about which theory or approach is best. You'll need to make an educated judgement based upon your own knowledge, research and professional experience.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|