|

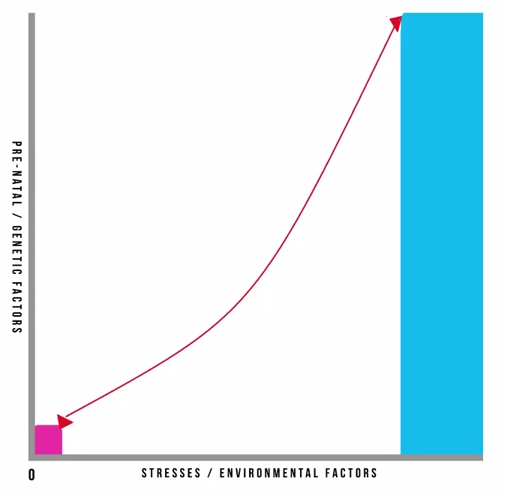

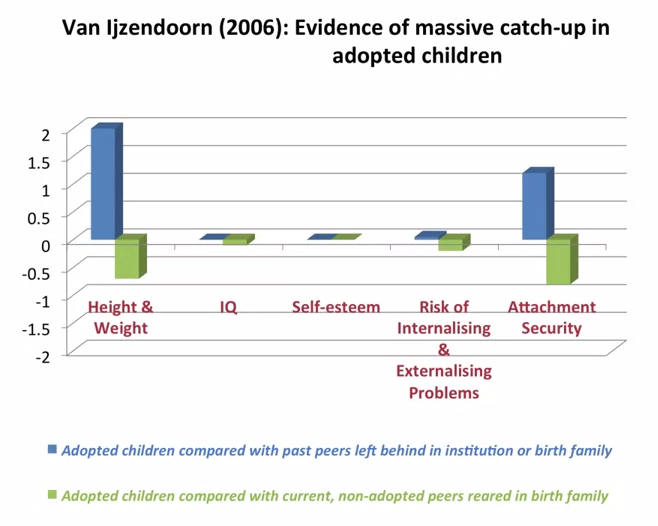

Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

0 Comments

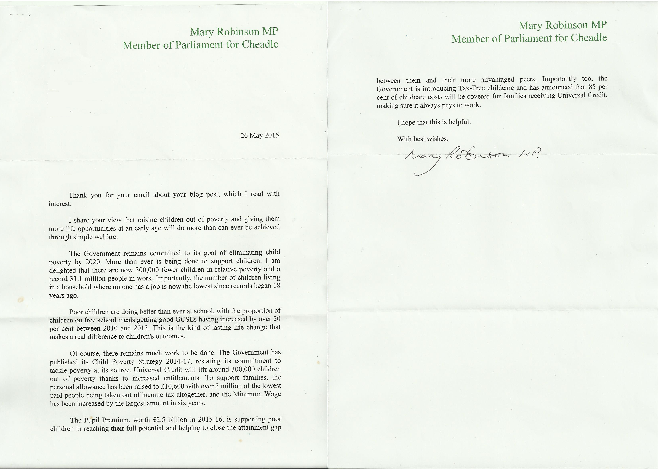

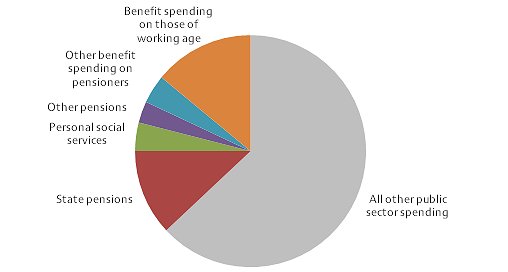

On 11 May 2015 I wrote a blog post entitled ‘welfare isn’t just about being a decent human being’. It was mainly about the impact of adverse childhood experiences and the need for the government to invest in a more preventative approach. I was encouraged today to receive a letter from my newly elected Conservative MP, Mary Robinson, in response to the concerns I outlined. She stated that she shared my “view that raising children out of poverty and giving them more life opportunities at an early age will do more than can ever be achieved through simple welfare”. I think that is the heart of the problem. Welfare isn’t simple. "Welfare" spending, according to the government’s public expenditure statistical analyses, accounts for 25% of the total and is defined as "social protection". It includes £28.5 billion on "personal social services". It includes spending on a range of things, such as looked-after children and long term care for the elderly, the sick and disabled. Unlike other elements of "social protection" it is not a cash transfer payment and in many ways has more in common with spending on health than spending on social security benefits. Another £20 billion of the spending counted under welfare is pensions to older people other than state pensions. That includes spending on public service pensions – to retired nurses, soldiers and so on. In addition to state pensions a further £28 billion is spent on pensioners, of which £15 billion goes on benefits specifically for that group, such as pension credit, attendance allowance and winter fuel payment, while the remaining £13 billion is largely spent on housing benefit and disability living allowance. So of the £205 billion or so spent on tax credits and social security benefits about £111 billion is spent on those over pension age and £94 billion on those of working age. The welfare state has changed a lot over the years and it is easy to lose sight of the principles upon which it was founded. Welfare, in my mind, is not just about cash payments but a whole system that works to protect and care for its citizens. In 1942, the Liberal politician William Beveridge, who the government set the task of discovering what kind of Britain people wanted to see after the war, declared that there were five "giants on the road to reconstruction": poverty, disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness. To defeat these giants, he proposed setting up a welfare state with social security, a national health service, free education, council housing and full employment. Whilst the needs of the nation have changed over the years the general premise is still tangible in the Liberal Democrats constitution: no one shall be enslaved by poverty, ignorance or conformity.

Here are my thoughts in response to the points raised by Mary Robinson MP in her letter: 'The Government remains committed to its goal of eliminating child poverty by 2020' According to Mrs Robinson, the government remains committing to not just reducing but eliminating child poverty by 2020. This is a tall order for any government, particularly when all the current research points to increased child poverty by 2020. The Joseph Rowtree Foundation estimates that by 2020 one in four families will be in poverty and if this were to happen it could cost the UK £35bn in today’s terms. '300,000 fewer children are in relative poverty' While one measure suggests Mrs Robinson is right, another can as easily be used to say she’s wrong. There’s no single definition of ‘child poverty’ in the UK. Official bodies measure it in three main ways. The first, takes a certain ‘low’ level of income and counts how many children live in households at or below that level. The second finds out the ‘middle’ income nationally and counts children who live in households earning less than 60% of it. This is known as the ‘relative’ poverty measure and is the one the Mrs Robinson was referring to. The other way is to count children in families which have poor living standards. For example, where there’s no safe place to play outdoors or they can’t afford things like school trips. So, there are 300,000 fewer children living in ‘relative’ poverty but this isn’t always a useful measure. As the government itself has conceded, when everyone’s income falls, this can mean poverty falling as well, which isn’t very intuitive. 'A record 31.1 million people in work' This latest round of figures put the employment rate at 73.5 per cent, it’s highest since records began in 1971. However, of the current 31.1 million working people in the UK at the end of March, only 53% are full time employees on someone’s payroll. The other 47% are what are referred to as ‘Self Drive Workers’ who are not dependent on one employer for their total income. In broad terms, this 47% have to find their own work. The UK has been moving away from this traditional work model for some years - and now it has become significant. Furthermore, data also shows us that there were 697,000 people on zero hour contracts in October-December 2014, compared with 586,000 in October-December 2013. The proportion of workers on a zero hour contract in October-December from 2000-2012 was under 1%. In 2013, it hit 2%. In 2014, it was 2.3%. A provision in the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, which was passed under the Liberal-Conservative coalition government and came into force on 26 May 2015, intended to ban clauses that allow employers to block zero-hours employees from holding jobs elsewhere; however, it has been described as toothless by lawyers. 'Poor children are doing better than ever at school' Research shows that of those eligible for free school meals in 2008/09, 73.3% did not achieve at least 5 GCSEs A* to C (including English and Maths) compared to 45.5% of pupils not eligible for free school meals. In 2013/14, 63% did not achieve at least 5 GCSEs A* to C (including English and Maths) compared to 35.8% of pupils not eligible for free school meals. However, the Joseph Rowtree Foundation warns that it is not possible to directly compare 2013/14 figures with earlier years due to the changes in methodology. Nevertheless, I would credit some of the improvement, whatever it might be, with the introduction of the pupil premium. 'The Pupil Premium is supporting poor children in reaching their full potential and helping to close the attainment gap' While, there is no doubt that the pupil premium was included in the Tory manifesto before the 2010 election, it has widely been accepted that the idea for an additional sum of money to go to students in receipt of free school meals not only came from the Lib Dems, but was the idea of Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg. Indeed, it is understood Mr Clegg first put forward the idea of a pupil premium back in 2002. 'The personal allowance has been raised to £10,600' Raising the personal allowance was a Liberal Democrat red line in 2010, which they delivered despite David Cameron telling the nation it was ‘unaffordable’. Indeed, increases in the personal tax allowance have improved the circumstances for many families in in-work poverty, but the most recent increase will not help those most in need who already have earnings below the tax threshold. Furthermore, under Universal Credit, 65% of any additional income recipients get from an increased tax allowance they will lose through reduced entitlement to Universal Credit. In March, the Chancellor set out in his budget the path of income tax bands from 2015/16 to 2017/18; raising the personal tax allowance to £11,000, and the higher rate threshold, to £43,300. This sounds great, but because tax bands are up-rated by inflation anyway, delaying the £11,000 by two years substantially reduces the benefit to taxpayers. In the absence of any policy intervention, the personal tax allowance would be expected to rise to around £10,760 in 2017/18 anyway. This means the announced measure is a rise of just £240, and a benefit of £48 in reduced tax for basic rate taxpayers, rather than the £80 they would receive had it been implemented this year. Conversely, the rise in the higher rate threshold is £400 higher than where it would fall if increased in line with inflation. Universal Credit will lift around 300,000 children out of poverty thanks to increased entitlement Universal Credit is a single monthly payment for people in or out of work, and will merge together some of the benefits and tax credits that they might be getting now. Universal Credit was launched in October 2013 with a gradual transition to be complete by 2017, replacing:

The good news is that it’s supposed to be simpler and there are no limits on how many hours a week people can work if they’re claiming Universal Credit. Instead, the amount they get will gradually reduce as they earn more, so they won’t lose all their benefits at once. You can find out more at the Money Advice Service. It is thought that Universal Credit will lead to an increase in employment due to improved financial incentives, simpler and more transparent system, and changes to the requirements placed on claimants. Overall, it is said, this could lead to the equivalent of up to 300,000 additional people in work from improved financial incentives. This is not the same as lifting 300,000 children out of poverty. There is cross-party support for the theory behind the benefit, but its delivery has been delayed and criticised. Unite union has claimed that it creates a division between a "deserving" and an "undeserving poor". In its initial estimate of the new system, the Institute for Fiscal Studies have said that the poorest are likely to do better, especially couples with children. However, the second earner in a family is likely to lose out in the long-term in many cases. Some charities have argued that, because of a broad-brush approach that universal credit takes, those with more complex benefit claims may lose out, such as some people with disabilities who go to work. Also, those without a bank account, or who do not have internet access, will have to seek advice to prepare for the new way this benefit is run and paid. Minimum wage increased by the largest amount in six years The 2014 increase in the adult rate lifted the real value of the minimum wage for the first time in 6 years through the biggest percentage increase since 2008. Great! Speaking at the Liberal Democrats party conference in Glasgow on 14 September 2013 it was Vince Cable that pressed for an increase in the minimum wage amid concerns that the lower-paid workers were still not benefiting from the “burgeoning economic recovery”. George Osborne on the other hand spoke on the 10 January 2014 to warn that a “self-defeating” increase to the minimum wage could cost jobs. Thankfully, on the 16 January 2014 he had a change of heart. Perhaps it was the Lib Dems that told him the “economy can now afford” to raise the rate? I agree that “there remains much work to be done”. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation is currently developing an anti-poverty strategy for the UK. As a part of this four year programme they have undertaken a review of effective strategies across the EU to determine their key characteristics. This review suggested that key to an effective strategy are clear mechanisms of responsibility and accountability, implementation plans and a monitoring and review process. It also found that clearly linking strategies to economic policy made them more effective. They assert that the Child Poverty Strategy 2014-17 (referred to in Mrs Robinson’s letter) does not sufficiently meet these criteria. In particular, while it does include some steps necessary to address child poverty, it neither assesses the impact of these measures upon child poverty, nor does it include milestones by which it can be held accountable during the course of its three years. In short, it does not offer any mechanism of accountability beyond achieving a reduction in the total number of children in poverty by 2017. Furthermore, it does not account for the impact of further reductions to welfare budgets over the coming year, which research for JRF by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows is likely to significantly increase the number of children in poverty. The JRF report suggested that the impact of changes to personal tax and benefit policy announced by the coalition government is likely to increase both relative child poverty by 200,000 in 2015/16 and absolute child poverty by 200,000 in 2015/16. It would seem there is indeed much more to do. I concluded my previous post by saying that Local Authorities need greater funding to hire more social workers so that caseloads are at a manageable level where they have the time to undertake intensive direct work with families again. The government needs to fund preventative and outreach services that can directly tackle problems before children become at risk of significant harm. Instead, proposals have been tabled to jail social workers who fail to prevent neglect, despite the necessary infrastructure to properly address it; and the shock result of a Conservative majority victory signals deeper, faster cuts than ever before. None of these points were addressed in Mrs Robinson's letter. Perhaps this was an oversight and I would welcome further dialogue. Communitycare has urged Social Workers to channel whatever they are feeling about the election result into something that isn't apathy. I have only just begun... Thanks for reading! Follow me on facebook and twitter to see future posts. This morning I was speaking with someone about ‘Stranger Danger’ and how this approach, in isolation, can lull children into a false sense of security. Statistically speaking a child is at greater risk from adults known to them and they need to be equipped with the skills necessary to spot and respond to risky situations. The idea that they can only be harmed by a faceless stranger is a dangerous one. Coincidentally, a couple of hours later I read an article in the Independent which reports ‘Stanger Danger’ does more harm than good. The charity Parents and Abducted Children Together is calling for "stranger danger" to be abandoned by schools and parents, and replaced with a more complex message about recognising dangerous situations rather than people. The above video from the 1980's looks very dated now and so is it's message (I've included it purely for nostalgia). Before this one there was "Charley Says" in the 1970s with his message about the danger of strangers in parks. Below I have posted some advice to help keep your child safe in the 21st century. You should select those that are most age appropriate.

If you have any more tips please share them in the comments. Have a great day! A couple of weeks ago I was asked about the causes, symptoms and likely consequences of troublesome and antisocial behaviours in children and young people. I’ve put together this post to offer a little bit of insight and advice to parents and those working with children displaying these kinds of behaviours. I hope that this post will help you by:

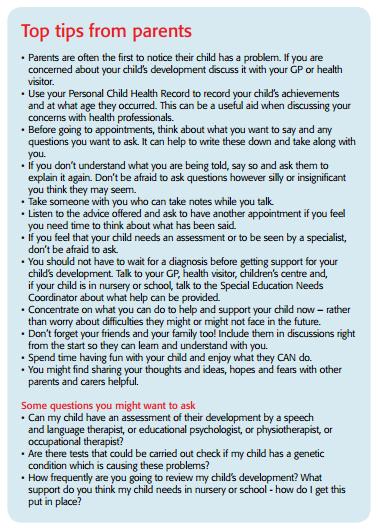

Nearly all children and young people can react in an angry or aggressive way if they are provoked. This ability is essential for survival, otherwise people would have difficulty defending their need for space and food. That is not what this post is concerned with; rather we are looking at cases where children are aggressive and angry a lot of the time. Children that do this far more than others, and in a way that prevents them from making satisfying relationships and getting on with activities and schoolwork. Before we get started I think it is important to firstly distinguish antisocial behaviour from the following: Occasional acts of antisocial behaviour or temper outbursts, once a fortnight or month, can be very frustrating for parents or teachers. However, if the child is well adjusted, has friends and is doing okay at school: adults should react calmly and not make too big a deal of what has happened; respond quietly (shouting at the child and calling them names can do more damage than the child’s original outburst); stay calm and apply a consequence that lasts a short time but is important to the child (for example, taking away a mobile phone, grounding the child or stopping them watching TV); talk when both sides have calmed down, about what happened and try to find ways to stop it happening again in the future. New antisocial behaviour in a previously well-adjusted child. This could include longer periods, up to a month or two, of aggression and moodiness in a previously reasonably adjusted child that after investigation seems to have a fairly obvious cause for the change in behaviour. For example: separating parents, failing an exam, breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend, moving to a new area or being bullied or abused. In these cases, adults should find a calm moment to talk to the child and discover what is on their mind; suggest possibilities to the child, as he or she may not be aware how upsetting an event has been; make the child feel that they are understood and there is sympathy for them; once the causes has been agreed, make plans for a more positive future. Usually the behaviour will settle down; if it doesn't, then a more significant problem should be considered. Long-standing antisocial behaviour can be defined as a general pattern of antisocial behaviour that has been present for several months in children and young people. In younger children this pattern can include: being touchy, having tantrums and being disobedient; breaking rules, arguing and rudeness; deliberately annoying other people, hitting, fighting, and destroying property around the house or school; or, bullying other children. If the pattern is persistent and serious enough to reduce the child’s ability to have a happy home life and/or get on at school, then the child is likely to meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. In older children and teenagers this pattern can include: lying and stealing (including breaking and entering into houses) and cruelty to other people or animals; leaving the house without saying where they are going (staying away overnight without permission); skipping school (truancy) or breaking the law, drinking alcohol inappropriately or taking drugs inappropriately; being a member of a gang and/or carrying a weapon. If the pattern is persistent and serious they are likely to meet criteria for a conduct disorder. The long-term consequences of a conduct disorder are often negative and the child may be at significant risk of: criminal and violent acts; misusing drugs and alcohol; leaving school with few qualifications; or becoming unemployed and dependent on state benefits. It is, therefore, important that those working with children and young people are able to identify those who are at risk so that effective interventions are available. If you are worried a child is displaying signs of oppositional defiant disorder or a conduct disorder you should seek a referral to CAMHS through the child’s GP. Many children and adolescents behave in a difficult or aggressive way from time to time. However, a minority do this persistently for several months in a way that hurts other people emotionally or physically. This can result in poor relationships with family, friends and peers at school. Young children may be very difficult to handle at home but perfectly well behaved at school. A small minority are the other way around. If problems persist they often spill out from home to include school and relationships with friends, who get fed up with the aggression. Bullying, for example, may happen during the school day or on the journey to and from school. Teenagers may go out into the local community in gangs and commit antisocial acts. There are many possible underlying causes of persistent anti-social behaviour. The first step in assessment should be to speak with the child or young person about their behaviour as well as any upsetting external events in their life. Parents and teachers are also a great source of information and insight regarding a child’s well-being. If a child has been performing worse than expected in school, it may be that they have a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia with reading. It is not necessarily the case that poor performance is due to laziness and failure to apply themselves. If a child is restless and fidgety, has difficulty sitting still and moves around more than other children, it is possible that they suffer from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). If present, the child will also have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating. They will not be able to control themselves in a wide range of situations such as queuing up at school, or taking turns in conversation. Schools should be able to refer children displaying these behaviours for assessment by an educational psychologist. If a child is persistently sad and miserable, it is possible that they are suffering from depression. If this is a concern you should request additional support through your GP. You may also find my article on Attachment Based Family Therapy useful. Ineffective parenting is often a strong contributor, particularly if there is little warmth or positive encouragement; low involvement and poor supervision of the child’s activities and whereabouts; inconsistently applied consequences; or negative and harsh discipline. Certain types of parenting are more likely to lead to antisocial behaviour either initially, or in maintaining it. For example, through inconsistent discipline the child may learn that they often get what they want by misbehaving, which in turn reinforces the behaviour. In many cases it may be that parenting is not ‘ideal’. This may arise simply out of exasperation, where the child is so annoying that the parents lash out angrily. Even if the original cause of the behaviour was an unhappy event, or a difficult temperament, if the child learns that he or she is rewarded by getting what they want through misbehaving they will do it more often. When children get little attention, they prefer to have negative attention than none at all. They will misbehave to gain the interest of the parent, even if through scolding or telling off. Reversing it provides a way forward for treatment. The way to reverse bad behaviour is to help parents build a positive relationship with their child. The parent should be supported in making clear the behaviour they want from the child and reward them through attention, praise or other good things. When the child does not behave, parents should use calm limits with clear consequences. Minor misbehaviour should be ignored whilst there should be proportionate consequences if it is more serious. Children must be given plenty of attention and encouragement for positive behaviour. This means instead of saying ‘stop running’ say something like “please walk slowly”, or “I really like it when you walk calmly”. If the child is making a mess at the dinner table, rather than saying “stop making such a mess”, you should give clear instructions as to what is desired and then praise them. These instructions are very clear and help the child understand what is required. Praise should be immediate as it allows the child to see a clear link between cause and effect. Barefoot Social Work can provide support on effective interventions, and an action plan can be formulated for your child or young person. Usually these work by helping parents and others around the child set clear limits and encourage positive behaviour. However, sometimes they can also help the young person learn techniques to control their temper. It may be that parenting classes will be beneficial or a period of intensive one-to-one parenting support. Please get in touch if you require any additional advice. Finally, it is important to note that if behaviour is suspected as being the result of abuse it is essential that concerns are reported to your local authority children’s safeguarding service.  Last week I started a 6 week course with the University of Edinburgh called The Clinical Psychology of Children and Young People. Child psychology is an area that particularly interests me and I'll post some of my own interpretations of how the material can be used in social work practice. I have studied it extensively in the past; however, I believe that as Social Workers we should continually refresh and build upon the knowledge that forms a basis for our practice. Like renewing a first aid certificate. I hope you find these posts interesting and helpful. This week we looked a child and adolescent development, factors that influence development, and models of developmental psychopathology. An understanding of children’s development helps us to interpret children’s well-being and mental health, and taking a developmental approach is important as it helps us to spot and interpret a number of different patterns and behaviours. Furthermore, looking at developmental outcomes (milestones) allows us to see when development is atypical and helps us to identify ways in which the child may need supporting. Children are qualitatively different from adults, they are not born as mini adults, and they are not born as empty vessels. They are complex in their development: some development occurs slowly and over time; other times development occurs rapidly such as in infancy and adolescence. To help, we can break it down into the following phases of development:

There are also different aspects of development:

Of course, the child develops as a whole and the different aspects of development do not occur in isolation. They all interact with one another. To understand this we look at patterns of development. Development isn't always progressive. There are various patterns of continuous change. Sometimes development can be very rapid and sometimes change is slow and gradual. At 18 months children start to engage in pretend play. Pretend play starts to decline during middle childhood as other forms of play become more prominent. This pattern of continuous development is often known as an inverted U function; where you can see that development increases and then declines. You can also have U shaped continuous change where you see an apparent decline that actually leads to an improvement in development. Often this is true of cognitive development where a child’s behaviour may look like it is becoming more difficult but actually, cognitively, they are re-evaluating how to perform the task and then their performance improves. Another pattern of development is stage changes. This is where you have changes in ability which seem to take quite a dramatic shift. A classic theory of stage changes is Piaget’s theory of development. He outlined four stages of cognitive development:

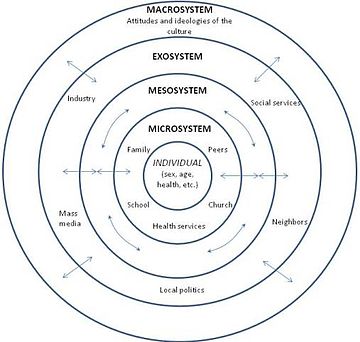

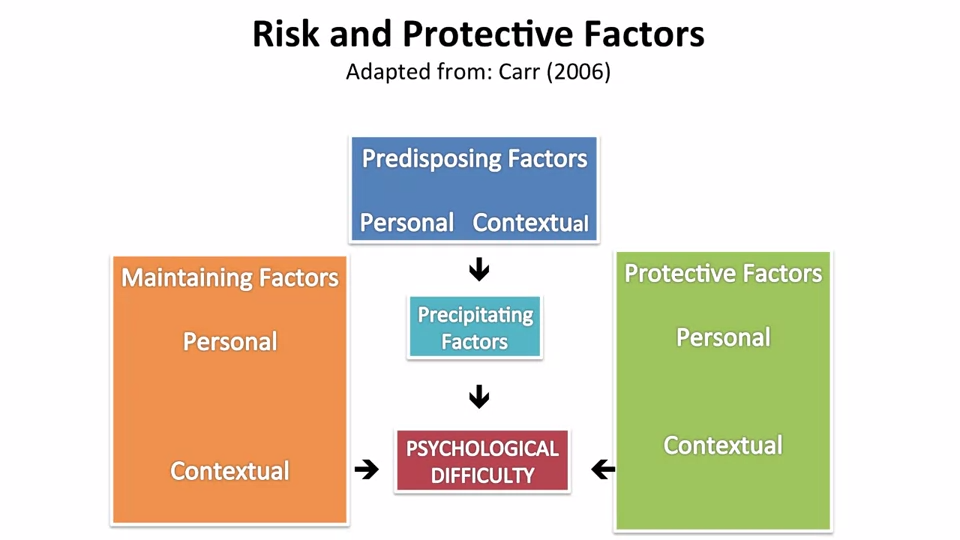

Piaget argued that each of these stages is typified by a new range of cognitive abilities or operations that allow children to cognitively perform at a different level. There are many influences on development. Firstly, biological influences like genetics and the brain. Genetics have a probabilistic relationship with development. They do not always determine or cause different developmental outcomes but they influence it through interacting with other genes and other things in our environments. An example of where genetics do have a direct link with development is in Down Syndrome. It’s a chromosomal abnormality that lead to a particular set of features and characteristics. Most genetic contributions are, however, probabilistic and they are seen as a risk or protective factors rather than direct causes. Twin research studies have been helpful in assessing the relative role of genes versus environment. As a result some mental health conditions and difficulties have been found to have a genetic component to them. For example, schizophrenia, ADHD, Autism, developmental dyslexia. However, genes aren't the whole story they are just a part of it. The Human Genome Project has helped to identify which genes or constellation of genes influence particular developmental and mental health outcomes. For example, we now know particular genes are involved with autism. We also know that some genes and combinations of genes act as protective factors as well. Brain development is also a significant biological influence. We know that there are important growth spurts which occur in the brain, firstly in infancy, and then later in adolescence. In the first two years of life we know that the brain grows enormously; but even more important are all the connections that are made in the brain that are related to the experiences the child has both physically, socially and emotionally. The more experiences a child has the more connections are maintained. If those experiences don’t occur or are reduced then the synaptic connections are pruned. This means that early brain development in infancy is very much a product of the environment the child is in; but in turn that brain development itself offers developmental opportunities for the child. The next major changes in brain development occur in adolescence which coincide with puberty. I’ll write a separate post on this later. Biological influences are really important but the environments within which children live and the people they live with are crucial to their development. We refer to these as social and environmental factors. Not only do the people a child lives with influence the food they eat (whether they have enough), the house and community they live in but also the people around them give them opportunities to learn and improve their understanding of the world and themselves. Also the people around them help them to form relationships and emotional bonds with others which can last in the long term. Social workers can use a tool (based on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological systems theory) to assess a child’s social and environmental factors. A child can complete a task with concentric circles with them in the middle; identifying who they think are important to them. Most importantly you should ask the child why they feel they are important. The third influencing factor on development is the interactions between biological, psychological and social influences. Most of a child’s development is influenced by both biological and social factors and how they interact. This area is often called the nature / nurture debate. For example, in early infancy, experiencing a loving, caring relationship with someone is crucial to the development of attachments. If this area is of particular interest you might like my posts on Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nurture and Nurture. Finally, we looked at models of developmental psychopathology and it’s influences on mental health and well-being. Developmental psychopathology focuses on normal and abnormal development and also adaptive and maladaptive processes. It shows us that there are a range of developmental trajectories that a child can take. Compas and colleagues undertook a review of adolescent development and highlighted that there isn’t just one developmental pathway or trajectory. They identified five:

This model is important as it highlights that adolescent development doesn’t just have one pathway. There are a range of different pathways that young people can find themselves on depending on a range of different factors and influences. Social Workers work with children and use skills based upon child development in their everyday practice. We observe children and learn something about how they’re developing and their well-being from our observations of them. We speak to children and learn about their development directly from them. We sometimes use little tasks and drawings and even short questionnaires and scales. If you'd like to find examples of scales and questionnaires that might be helpful in your practice please take a look at the tools section of this website.

Next week I'll be covering the topic of resilience. Please follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss it!

Whitney was right in 1985 when she sang “the children are our future” but does the government believe this only applies if you’re from a certain background? I recently read an article by Dr. Charles Lewis where he asks if the US is witnessing a new wave of social Darwinism. Perhaps the UK should also reflect upon this question. What kind of future will the most vulnerable children in our society have unless we invest in them and their families both financially and emotionally?

The shock result in the UK general election was a wakeup call and we need to re-examine how social issues are discussed within the media if they are to be seen as relevant to the electorate. Labour are reportedly “soul searching” whilst the Liberal Democrats have launched a “fightback” but we should all be engaged in the debate. Many people believe that the core tenet of democratic voting is that we should vote for those that best represent our personal interests; however, we should all have a vested interest in the welfare of those living in poverty and with adversity, and we know that the socially excluded are less likely to vote and have their interests represented.

In my post on the 11 May 2015 I described how poverty is considered to be the best predictor of mental health disorders because it is a predictor of all the other things that are causal. I explained how adverse childhood experiences (ACE), many of which are compounded by poverty, are strongly related to adverse behavioural, health and social outcomes; creating a cyclic effect where those with higher ACE counts have higher risks of exposing their own children to ACEs.

These childhood experiences place a huge burden on the NHS, social care and judicial system. Surely it is plain to see that investing in services earlier will not only improve the life chances of the most vulnerable children in our society, but it will also alleviate some of the pressure on other services. The government needs to invest in an infrastructure that can be preventative as well as reactive. We would all benefit from it. If we are concerned about crime, we might want to look at the causes of crime. Childhood adversity is associated with adult criminality and it has been recommended in a 2013 study that to decrease criminal recidivism, treatment interventions must focus on the effects of early life experiences. Indeed, a UK ACE study found that preventing ACEs in future generations could reduce levels of violence victimisation by 51%, violence perpetration by 52% and incarceration by 53%. If we are concerned about the NHS, we might want to look at the causes of the negative health outcomes that place a burden on its service. Previous studies have found that there is a dose-response relationship between adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes. For a person with an ACE score of four or more, the relative risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was around two and a half times that of someone with an ACE score of zero. For hepatitis, it was also two and a half time times. A person with an ACE score of seven or more had triple the lifetime risk of lung cancer and three and a half times the risk of ischemic heart disease. In 2014 a Bulletin of the World Health Organization described how people in the UK with at least four adverse childhood experiences were at significantly increased risk of many health-harming behaviours. They said modelling indicated that prevention of adverse childhood experiences would substantially reduce the occurrence of many health-harming behaviours. But that's not all... they also found that preventing ACEs in future generations could reduce levels of early sex (under 16 years) by 33%, unintended teen pregnancy by 38%, smoking by 16%, cannabis use by 33%, heroin/crack use by 59% and poor diet by 14%. Until we see political and social reform Social Workers can help the vulnerable groups they support by working in preventative ways, rather than concentrating solely on crisis intervention; act as advocates for people that encounter injustices; empower people to become involved in decisions that affect them; challenge oppressive working practices; and most importantly, advocate for political and social change. It is important for social workers to engage in the current debate about how to prevent harmful childhood adversity and challenge structural inequalities that compound them. If you would like to learn more, I've added some recommended books at the end of this post. You should also take a look at this video of Mark Bellis at the World Health Organisation: For the last few weeks I’ve been posting about a six week course I’ve been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. Today is the penultimate week and we have been consolidating the last four weeks learning and identifying how these psychological insights can help us and our clients maintain mental health and well-being. We looked at a recent UK Government report into well-being and considered how we might be able to incorporate its findings into our professional practice. The report was drafted by a team at the new economics foundation (NEF) and presented evidence for things individuals could do themselves to achieve greater well-being. They concluded that people should follow a well-being equivalent of the ‘five fruit and vegetables a day’ rule. You can view the full report here. In summary, they recommended the following:  Keep active When people are physically active they tend to have better mental health. Simple things like going for a walk, mowing the lawn, washing the car are just as effective as going to the gym or running.  Maintain relationships There are things that people can do every day to maintain their connectivity with other people, and to maintain their relationships. Phone a relative/friend, send a postcard, write a letter, or even use social media.  Learn It doesn't have to be formal learning at a university or college, it could be as simple as reading a newspaper/book, doing a crossword or going to the library. Things that keep the brain active and engaged are good for our mental health.  Give Research has shown that people who give – time, money and/or energy – tend to have better mental health than those who don’t.  Be mindful There's a growing body of evidence that an approach called mindfulness is good for our mental health. And that means that every day we can make sure, we can bear in mind, to be aware of the things that we're looking at, the things that we're smelling, the things that we're seeing, our own thoughts, and the functioning of our own bodies, to be aware of and to be engaged with the world rather than just simply passively moving through it. We also looked at a selection of resources available to help maintain mental health and well-being. I thought you might also be interested as they can be used to inform personal or professional strategies. Here they are... Catch It, Check It, Change It The University of Liverpool has recently developed a smartphone app for iPhone and Android. Designed to introduce key ideas from cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), the app allows users to keep a record of their moods, therefore allowing them to reflect on what affects their feelings. It is hoped that this, in turn, will help them to control their moods. It is not proposed that the app could or would ever replace direct therapy; rather the purpose is to provide an understanding of CBT; helping people to gain a little more insight into, and control over, their emotions. Activity Scheduling Activity is an excellent anti-depressant. But when people are depressed, they often find it difficult to motivate themselves to become active. So clinical psychologists often give their clients simple diaries to keep track of their activity. The BBC’s Activity Scheduling guide is a fantastic resource that you could use yourself or incorporate into your practice with clients. Graded Exposure Anxiety is a common problem which can be reduced through a well-tested therapeutic approach called graded exposure. The basic aim is to help people gradually build up their confidence in addressing a problem that causes them anxiety; step by step. You might find this graded exposure activity sheet helpful. Structured Problem Solving Research has found that rumination can be a key problem in maintaining mental health. However, it has also been found to be a protective factor for people if they had well-developed skills in ‘adaptive coping’. One approach to helping people develop these kinds of skills is called ‘structured problem solving’. This really means breaking down problems into their constituent components and generating possible solutions for each element. Again, the BBC has a simple worksheet available which you might like. Next week will be the last session and I've been told we will be looking at how we can use what we have learned so far to design and commission better mental health and well-being services. If this is something you'd be interested in reading about please follow me on facebook so that you don't miss it. Have a great week! Adolescent 'behavioural problems' are a huge source of referrals for local authority children's services across the country, after parents and teachers struggle to find strategies that work. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that many rebellious and unhealthy behaviours or attitudes in teenagers can actually be indications of depression. The following are just some of the ways in which teens “act out” or “act in” in an attempt to cope with their emotional pain:

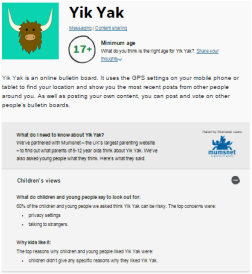

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) has been the traditional route for support in the UK. However, waiting times and thresholds are at an all time high. More and more services are commissioned only for those children presenting with the signs and symptoms of a diagnosable disorder or condition which means that those struggling with less obviously acute or harder-to-label problems are often not eligible for treatment. As a result Children’s Social Workers are increasingly working to help families through what can be a very distressing time, and there is a renewed focus on specialised training to meet this need.  Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) is a manualised, empirically informed, family therapy model specifically designed to target family and individual processes associated with adolescent depression. However, I have found it has strong applicability when working with all families with teenagers. It was first developed by Prof. Guy Diamond, Suzanne Levy and Gary Diamond; all of whom have received international acclaim for their work in this area. The model is emotionally focused and provides structure and goals; thus, increasing the Social Workers intentionality and focus. It has emerged from interpersonal theories that suggest teenage depression can be precipitated, exacerbated, or buffered against by the quality of interpersonal relationships in families. It is a trust-based, emotion focused model that aims to repair interpersonal ruptures and rebuild an emotionally protective, secure-based, parent-child relationship. Teenagers may experience depression resulting from the attachment ruptures themselves or from their inability to turn to the family for support in the face of trauma outside the home. The aim of ABFT is to strengthen or repair parent-child attachment bonds and improve family communication. As the normative secure base is restored, parents become a resource to help their child cope with stress, experience competency, and explore autonomy. I believe it should be integrated into the practice of all children’s social workers. If you’d like to learn more you can buy the latest book, Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Depressed Adolescents, here. I've written a couple of posts recently about Protecting Young Children Online and Protecting Big Kids Online. I was thrilled at how many times they were viewed and shared (Thank you!) and I hope they have helped you to feel more confident in safeguarding your children in the digital age. Since I last posted I've found the new Fire HD Kids Edition. It has some great easy-to-use parental controls where you're able to manage usage limits, content access and educational goals, plus there's a 2 year worry free guarantee! It looks fab! Children’s apps and websites were in the news on privacy grounds earlier this week, after the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) announced a review of how these services collect data on their young users. It will form part of an international project, coordinated by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, and will look at 50 websites and apps, particularly what information they collect from children, how that is explained, and what parental permission is sought. The websites and apps will include those specifically targeted at children, as well as those frequently used by them. So how can parents decide which sites, apps and games are appropriate? Today I was emailed about the NSPCC's updated Net Aware guide which helps parents to understand what their children are doing online and hopefully maintain open channels of communication. It's a huge database providing information on sites, apps and games. It tells you what it is, why kids like it and provides an age rating to help parents judge whether it's appropriate for their child. After having a look through the site I realised that I probably haven't heard of half of them before.  Research by the NSPCC earlier this year found that many parents have gaps in their online knowledge and don't talk about the right issues with their children. For example, Tinder, Facebook Messenger, Yik Yak and Snapchat were all rated as risky by children, with the main worry being talking to strangers. However, for the same sites the majority of parents did not recognise that the sites could enable adults to contact children. Although eight out of ten parents told the NSPCC that they knew what to say to their child to keep them safe online, only 28% had actually mentioned privacy settings to them and just 20% discussed location settings. One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication. Here are my top tips:

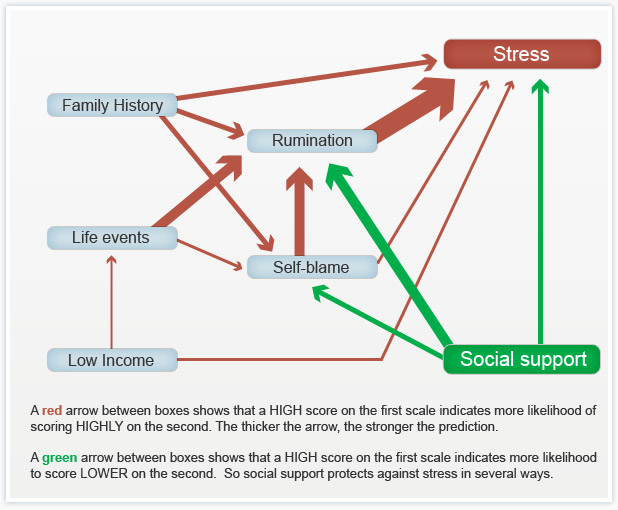

Take a look at the NSPCC guide and let me know what you think. For the last three weeks I've been posting about a course I've been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. This week we focused on the role of psychological mechanisms in the development of mental health problems and the maintenance of well-being. The sources we were presented with suggest that a psychological perspective adds a vital additional element to the ‘nature-nurture’ debate, because it is through these psychological mechanisms that we interpret and respond to the world.  Our course leader Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool, argues that our mental health is essentially a psychological issue, and that biological, social, and circumstantial factors affect our mental health and well-being by disrupting or disturbing psychological processes. The way in which we make sense of the world, the way in which we understand ourselves, who we are as people, the way we make sense of other people, the way that we react socially, how we think about the future, and how we think about the world in general, this sense making, this framework of understanding of the world is fundamentally important in determining our mental health and well-being. To get us started we are provided with a copy of Peter Kinderman’s, A Psychological Model of Mental Disorder. This article discusses the relationship between biological, social, and psychological factors in the causation and treatment of mental disorder. He suggests that a comprehensive psychological model of mental disorder can offer a coherent, theoretically powerful alternative to reductionist biological accounts while also incorporating the results of biological research. We are told that Peter was able to test out some of these ideas in a research study that he conducted with the help of the BBC; testing out the idea of whether a combination of different factors could predict the level of mental health difficulties and well-being that a person was experiencing. They were interested in whether biological factors, which were measured by looking at the experience of mental health problems in a person's family of origin, in their parents and in their siblings, could predict mental health problems, which would then have a variety of psychological and social consequences. Or whether, on the other hand, life events like trauma in early childhood or experiencing a range of negative life events in the last six months would predict people's mental health problems. Or as they hypothesised, whether psychological factors - rumination, where people would go over and over things in their minds, or self blame, where people would blame themselves for the difficulties they were experiencing - would explain more of a person's mental health problems. When they looked at the results, it seemed that social factors were very influential in predicting people's mental health problems, with biological factors playing a part, but a less important part. But importantly, both social and biological factors were mediated by the psychological factors. So, they asserted, rumination and self blame seem to be the gateways towards mental health problems.

You can see the paper itself and also a brief magazine article (Rumination: The danger of dwelling) hosted by the BBC on their website. Peter says that this way of thinking about mental health has some quite profound consequences. If you realise the way in which a person thinks about the world, the way in which a person responds to events in their lives, makes a difference to their mental health, to their well being, to anxiety and depression, it does change the way in which we should approach mental health problems. It brings it back to the idea that how we think about the world matters. Because it changes the way in which we feel and behave. This gives us some different opportunities for how to help people who've got emotional difficulties. But it's also important for people who themselves are suffering, because rather than blaming them for their difficulties, it means that there are things that they can do themselves to get out of the problems that they find themselves in. It gives people a sense of agency and control over their own mental health. Finally we were invited to take part in some of Peter’s current research: Causal and mediating factors in mental health and wellbeing. A follow up study to the research that has formed the basis of this week’s part of the course. At the end of the course we are asked if we believe adding psychological processes to the mix add anything useful to our understanding of the ‘nature-nurture’ debate? Do we think these kinds of factors are important in determining our mental health and well-being? Do we think an understanding of psychological processes mean that we can offer more useful ways of helping people - perhaps through therapy? What do you think? If rumination is posing a difficulty for you or a client there are a couple of things you could try.

I read in the Guardian today that Downing Street have announced Iain Duncan Smith will remain Work and Pensions Minister following the Conservatives electoral win last week. They reported that he will “continue with his task of “making work pay and reforming welfare” as the government implements the universal credit reforms and imposes £12bn in cuts on the welfare budget”. This will be in addition to the £30bn that the Institute of Fiscal Studies say the Tories will also need to find in real-terms cuts from ‘unprotected’ departments, including social care and defence. The news of a Tory win last Thursday didn’t go down well with some. There were large demonstrations in London over the weekend; although it was only the violent clashes with riot police outside Downing Street that seem to have made the headlines. However, the arrests don’t seem to have deterred them; and the anti-austerity group behind the protest are planning another demonstration outside the Bank of England next month. Like many, I am genuinely worried about the proposed cuts and what that means for social work. I posted last week that Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology & Head of the Institute of Psychology, Health & Society at the University of Liverpool, has said that one of the best predictors of mental health disorders by far, whether it’s depression, suicidality, psychosis, are all life events. The strongest predictor all by itself is poverty. Not because poverty by itself causes depression, but because it is a predictor of all the other things that are causal. So poverty has been described as the causes of the causes. And those other causes are a whole raft of things – childhood neglect, childhood abuse, loneliness, and problematic parenting, which is usually inter-generational. It’s not about bad parents, it’s about who themselves haven’t perhaps had the sort of childhood that predisposed them to good enough parenting. And so the cycle continues… There are currently 3.5 million children living in poverty in the UK. That’s almost a third of all children. 1.6 million of these children live in severe poverty. But what the Conservatives don’t want you to know is that 63% of children living in poverty are in a family where someone works. This is why welfare, preventative services, family support and intervention are so vital. We need to break the cycle by providing welfare that brings children out of poverty. Services need to be funded and available to support the most vulnerable and improve parenting so that children can be safeguarded in the care of their family. However, services that were once available have been decimated through cuts over the course of the last parliament and they look set to get worse by 2020. But welfare isn’t just about being a decent human being; it also makes economic sense. In the mid-'90s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discovered an exposure that dramatically increased the risk for seven out of ten of the leading causes of death in the United States. In high doses, it affects brain development, the immune system, hormonal systems, and even our DNA. People that are exposed in very high doses have triple the lifetime risk of heart disease and lung cancer and a 20-year difference in life expectancy. It’s not about eating GM foods. It's childhood trauma: things like abuse or neglect, or growing up with a parent who struggles with mental illness or substance dependence; things that we know, according to Peter Kinderman, are strongly linked to poverty. Take a look at this 2014 TED talk by Nadine Burke Harris. The Adverse Childhood Experiences study found that there was a dose-response relationship between ACEs and health outcomes: the higher your ACE score, the worse your health outcomes. For a person with an ACE score of four or more, their relative risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was two and a half times that of someone with an ACE score of zero. For hepatitis, it was also two and a half times. For depression, it was four and a half times. For suicidality, it was 12 times. A person with an ACE score of seven or more had triple the lifetime risk of lung cancer and three and a half times the risk of ischemic heart disease, the number one killer in the United States of America. Now, you might be thinking – this is interesting but it’s about a study conducted in the United States. Can we rely on the findings to support welfare as a public health initiative in the UK? Well…. In 2014 Mark Bellis and colleagues published a retrospective study to determine the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. They also found that increasing ACEs were strongly related to adverse behavioural, health and social outcomes. Compared to those with 0 ACEs those with 4+ ACEs had a greater risk of poor educational and employment outcomes; low mental wellbeing and life satisfaction; recent violence involvement; incarceration; recent inpatient hospital care and chronic health conditions; and early unplanned pregnancy. All of this suggests a cyclic effect where those with higher ACE counts have higher risks of exposing their own children to ACEs. There are more studies here, here, and here. It’s clear that these childhood experiences place a burden on a UK population’s health, NHS and judicial system; and there is a strong case for the government to invest in effective interventions to prevent them. That’s why the World Health Organization and global health partners are promoting research into the extent and impact of them around the world. So, why is it that during this time of growing evidential support for preventative work, is the government promoting a false economy through welfare cuts and dismantling the welfare system??? In 2007 Lynne Wrennall identified failures in the UK’s work with vulnerable children. She believes that the morale of a “great many caring, compassionate, highly competent, and creative social workers” would be “vastly improved if their primary function was again focused on assisting, rather than dismantling, families, upon working creatively toward this end with the resources and the legislative and managerial support to do so”. However, she also acknowledges that sometimes “an out-of-home placement is unavoidable”, and that in those instances “a programme leading towards re-unification and rehabilitation must be implemented”. She advocates for a “European model” that “strongly favours an educative role for social workers and a primary task of maintaining family unity, utilising and coordinating services toward this end and focusing on `educating’ the parents and family in social norms and values”. But for this to happen the conservative government would first need to reframe the way it thinks about the most vulnerable people in our society and invest in their future wellbeing and health. Local Authorities would need greater funding to hire more social workers so that caseloads are at a manageable level where they have the time to undertake intensive direct work with families again. They would need to fund preventative and outreach services that can directly tackle problems before children become at risk of significant harm. Instead, proposals have been tabled to jail social workers who fail to prevent neglect, despite the necessary infrastructure to properly address it; and the shock result of a Conservative majority victory signals deeper, faster cuts than ever before. Communitycare has urged Social Workers to channel whatever they are feeling about the election result into something that isn’t apathy, because the profession looks set to be needed like never before and I have to agree. P.S. Please follow me on facebook and/or twitter to see posts as they're added to my site

For the last two weeks I've been posting about a course I've been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. So far I've found it really interesting and it has challenged me to reflect on my practice and past cases.

Last week, we discussed the role of biological processes and mechanisms. We were urged to consider how our emotions, thoughts and behaviours are related to neurotransmitter and other biological mechanisms; and to appreciate how this shapes service provisions. This week we were taught about the role of psychological mechanisms in the development of mental health problems and the maintenance of well-being. The material we were presented with highlighted a vital element to the ‘nature-nurture’ debate, asserting that it is through these psychological mechanisms that we interpret and respond to the world. Many psychologists and psychiatrists believe that it's by looking at the nurture side of the equation, by looking at differences between people in terms of the things that happened to them that we can start to explain mental health issues. Our lecturer says that undoubtedly just from the sheer weight of evidence psychosocial events are the more powerful predictor. We heard about Professor John Read, who believes that the best way to explain the origin of mental health problems - and especially differences between people - is by looking at life events and the different experiences we have in our lives. To get things started we are presented with an article from The British Journal of Psychiatry within which Pat Bracken and colleagues set out an argument for a more social psychiatry; arguing that social factors are the most important determinants of our mental health. Here is their 2012 paper if you’d like to have a read yourself. They argue “… that psychiatry is in the midst of a crisis. The various solutions proposed would all involve a strengthening of psychiatry’s identity as essentially ‘applied neuroscience’. Although not discounting the importance of the brain sciences and psychopharmacology, we argue that psychiatry needs to move beyond the dominance of the current, technological paradigm. This would be more in keeping with the evidence about how positive outcomes are achieved and could also serve to foster more meaningful collaboration with the growing service user movement…”. They says that: ”… Although mental health problems undoubtedly have a biological dimension, in their very nature they reach beyond the brain to involve social, cultural and psychological dimensions. These cannot always be grasped through the epistemology of biomedicine. The mental life of humans is discursive in nature. … The evidence base is telling us that we need a radical shift in our understanding of what is at the heart (and perhaps soul) of mental health practice. If we are to operate in an evidence-based manner, and work collaboratively with all sections of the service user movement, we need a psychiatry that is intellectually and ethically adequate to deal with the sort of problems that present to it. As well as the addition of more social science and humanities to the curriculum of our trainees we need to develop a different sensibility towards mental illness itself and a different understanding of our role as doctors…”. Next we looked at a paper recently published in the journal ‘Schizophrenia Bulletin’ by Filippo Varese and colleagues that I found very interesting as a Children’s Social Worker. Filippo and colleagues explored the link between traumatic childhood experiences (poverty, abuse, etc) and later psychotic experiences. We are told that their work was important because many people tend to think that such serious problems as hallucinations and delusional beliefs are quintessentially biological in origin, and this paper suggests an important social dimension. They looked at a wide range of studies that examined the links between life events and later psychosis. Their conclusions were: ”…Evidence suggests that adverse experiences in childhood are associated with psychosis. To examine the association between childhood adversity and trauma (sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional/psychological abuse, neglect, parental death, and bullying) and psychosis outcome … we included 18 case-control studies… 10 prospective and quasi-prospective studies… and 8 population-based cross-sectional studies... There were significant associations between adversity and psychosis across all research designs …. patients with psychosis were 2.72 times more likely to have been exposed to childhood adversity than controls. The association between childhood adversity and psychosis was also significant ... These findings indicate that childhood adversity is strongly associated with increased risk for psychosis…” We are directed to read a paper by Ben Barr and colleagues which looked at how the recent economic recession impacted on suicide rates - a rather dramatic (and sad) example of how social factors impact on our mental health. They found that between 2008 and 2010, there were 846 more suicides among men than would have been expected based on historical trends, and 155 more suicides among women. Next we look at a paper in ‘The Psychologist’ by John Read which expresses some frustration at how attempts to integrate biological, social and psychological perspectives on mental health problems tend tacitly to assume that the most important elements are biological, with the social and psychological elements somewhat downplayed. Read argues that people pay lip-service to the bio-psychosocial model, but undermine it in practice. He gives the example of a senior colleague who: ”…acknowledged some of the recent research about the role of psychosocial factors influencing schizophrenia. He concluded, however, that ‘the schizophrenia wars were over years ago’. He was referring to the truce established under the banner of the ‘bio-psycho-social’ model, which says that schizophrenia is an interaction between a genetically inherited predisposition and the triggering effect of social stressors…” He concludes: ”…The simple truths are that human misery is largely inflicted by other people and that the solutions are best based on human – rather than chemical or electrical – interventions…”. Reading this article I can’t help but remember the men I worked with at a service for ex-offenders with drug misuse issues. Most had a dual diagnosis, a number of them schizophrenia, and all had experienced some form of trauma in their childhood or youth. Each of them received medication to treat the condition but “human intervention” was patchy. Our lecturer tells us that we know following 20, 30 years of research that there is no specific genetic predisposition to any of the mental health disorders. And we know that the best predictors by far of all of them, whether it's depression, suicidality, psychosis, are all life events. The strongest predictor all by itself is poverty. Not because poverty by itself causes depression, but because it is a predictor of all the other things that are causal. So poverty has been described as the cause of the causes. And those other causes are a whole raft of things - childhood neglect, childhood abuse, loneliness, and problematic parenting, which is usually inter-generational. It's not about bad parents, it's about parents who themselves haven't perhaps had the sort of childhood that predisposed them to good enough parenting. This is why preventative services, family support and intervention are so vital. Parents need to be taught and supported to break this cycle; and so that children can be safeguarded in the care of their family. This week’s session has left me with little doubt that I favour the social model (this probably won’t come as a surprise to you as I am a Social Worker and Sociology graduate). I hope that following today’s general election we see a greater investment in mental health services as promised in so many of the parties manifestos. I also hope that the next government values children’s social care enough to invest in it and address the woefully inadequate funding for preventative / support services in this country. Spending cuts and austerity have most definitely fallen hardest on the most vulnerable. Have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on facebook so you don’t miss next week’s post on psychology and mental health. I was overwhelmed at the positive response I got for my earlier post about Protecting Young Children Online (Thank you for sharing!) so as promised I am following up with one for older children in Key stage 2. The tips below should be used in addition to the security measures outlined last time. Of course, you might want to give them access to a greater range of websites now that they are older; however, you should still ensure that they are age appropriate. Technology and the internet has changed a lot since we were kids and keeping up to date can be a challenge. Many parents feel overwhelmed as their children’s technical skills seem to far exceed their own. However, children and young people still need support and guidance when it comes to managing their lives online if they are to use the internet positively and safely. There are a number of books and online resources available to increase your technical knowledge and skills. If you aren't that confident online or with electronic devices it might be worth brushing up now before the kids really surpass us in their adolescent years. Is your child safe online? A Parents Guide to the internet, facebook, mobile phones & other new media is a great starting point. It covers all forms of new media - iPhones, apps, iPads, twitter, gaming online - as well as social networking sites. If you want to learn more of the techie stuff behind maintaining personal privacy Internet Privacy For Dummies is a really accessible quick reference guide. Topics include securing a PC and Internet connection, knowing the risks of releasing personal information, cutting back on spam and other e–mail nuisances, and dealing with personal privacy away from the computer. The UK Safer Internet Centre offers a Parents' Guide to Technology. It introduces some of the most popular devices, highlighting the safety tools available and empowering parents with the knowledge they need to support their children to use these technologies safely and responsibly. The NSPCC and NetAware have also created a brilliant resource detailing sites, apps and games that they have reviewed. It's a huge database telling you what they are, why kids like them, and it gives an age rating to help you to judge whether it's appropriate for your child. Anyway, back to protecting your big kids... One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication.

It’s never too early or late to start talking to your child about staying safe online. There are a number of great resources available for parents and professionals to access and download. On my earlier post I showed you Smartie the Penguin by ChildNet. For children in key stage 2 there’s The Adventures of Kara, Winston and the SMART Crew. It’s a cartoon and each of the 5 chapters illustrates a different e-safety SMART rule.  is for keeping safe. Be careful what personal information you give out to people you don’t know  is for meeting. Be careful when meeting up with people you’ve online chatted to online.  is for accepting. Be careful when accepting attachments and information from people you don’t know they may contain upsetting messages or viruses.  is for reliable. Always check information is from someone reliable and remember some people may not be who they say they are.  is for tell. Always tell a trusted adult if something or someone online is making you worried or upset. You can watch the full movie online or download it to a device for later. For children at the older end of this age group, CBBC has an online comedy drama called Dixi. Dixi both encourages children to enjoy the creativity of the internet while also getting them to think about the potential dangers of social networking, from online privacy and safety settings, to the real-world consequences of cyber bullying. Cheryl Taylor, Controller of CBBC, says: “It’s important to raise awareness about safety online and Dixi does this in an engaging, educational and entertaining way”. There are also games that complement the drama for children to access through their website. You could also sit down together to watch the film below by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre. It’s called 'Jigsaw' and is suitable for this age group. It helps children to understand what constitutes personal information and enables children to understand that they need to be just as protective of their personal information online, as they are in the real world. It also directs them where to go and what to do if they are worried about any of the issues covered. It could be a great conversation starter and open up the channels of communication. I hope that you find this helpful. It can be a little intimidating when our children venture into the virtual world but with support and boundaries they will have have access to a resource with huge educational and social value. I'll post again soon with tips for supporting Teenagers / Young People in the digital age. Please follow me on facebook so that you don't miss it!