|

The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred system was for Social Workers to have the time and skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. I posted about this in Direct Work with Children and Young People: Houses and Faces and described a couple of activities that I have found particularly useful in the past.

Direct work with Children and Young People demands time, skill and creativity. It’s about more than simply asking the child “how are things at home?” and whilst pen and paper may be sufficient for some children, others may need different media to make sense of their wishes and feelings. That’s why I find it particularly helpful to have a ‘Social Work Tool Kit’. It’s nothing fancy – many of the items can be kept in a small bag/box in your car and brought out as and when they're needed. Most Social Workers will already have an idea of what’s useful to them and the children they work with; but after receiving a couple of emails on the subject I wanted to post my recommendations. So, here they are… (*There are affiliate links embedded in all the pictures)

Thanks for reading! Please let me know what's in your Social Work Tool Kit by commenting below.

0 Comments

I’ve seen a couple of ‘Missing Child’ posts on Facebook this week and I wanted to explain why I won’t be sharing them. They are always heart wrenching pleas for help. Some of them, I have no doubt, are genuine. I know this as a quick search on Google and I find that the police are also concerned for their whereabouts and are actively searching for them with the support of authorised charities and agencies. However, there are some that are not what they seem*.

Some are simply a hoax and some of them are not ‘missing’ at all. The child may have been adopted due to the risk of significant harm; they may be in hiding with their other parent as a result of serious domestic violence within the home; or the whole family may be in police protection and the concerned ‘father’ is not who he claims to be. Furthermore, ‘missing adults’ may wish for their location to remain anonymous, and they do have that right which we must respect. As virtual strangers we do not know the circumstances of their ‘disappearance’ and we should trust in the expertise of professionals to get the full picture. In October 2013, there was a case in Sweden where a father published a photo of his missing children and asked for help in finding them. Thousands of people helped by sharing the post and finally one person recognised the children and let him know where to find them. What Facebook users weren't aware of was that the mother and her children were living under protection and with a new identity after leaving the father. When he found them they were forced to move again, but the consequences could have been much worse. Jayne has also been in touch to say that she "know[s] of a Father who'd been rehomed with his children and the Mother found her children who were in protective custody from her using facebook. Really good to make people aware!!". In other cases here in the UK, the birth parents of adopted children are using Facebook and other social networking sites to track down their children, flouting the usual controls and safeguards. Incidents are becoming more and more common and many local authorities are now advising adoptive parents not to include photographs in their annual letters, in case these are posted online in an attempt to trace the child. F.m has said: "We have 3 children who are adopted, and we had this happen. We had sent the birth family photos with the letter of our girls as bridesmaids. They were then posted on Facebook as 'abducted, please help us find them', very scary indeed. They were removed from their birth family for very good reason, and must be protected from them for life. Social media is dangerous and we live in fear of someone posting something which helps birth family find them." So, what can you do to help?

Thank you for all the likes and shares on this post. Please take a look at the rest of my blog. You can also follow me on facebook and twitter. * This post is not referring to genuine appeals for information by the police or any authorised charity acting on their behalf.

Childhood is a time of rapid change. Some of these changes are obvious, such as height gain, language ability and physical dexterity. Others are less obvious, such as how children make sense of the information in their environment. To understand the rapid changes of childhood, children’s abilities are often judged against developmental milestones, such as acquiring language (babbling, talking), cognition (thinking, reasoning, problem solving), motor coordination (crawling, walking) and social skills (identity, friendships, attachments). But how does digital technology influence the acquisition of these important skills? Does technology hinder a child’s physical, social and cognitive development, or does it provide exciting opportunities for learning?

The entertainment and interactivity of tablets and smartphones has made them attractive to children. Touch-screen interfaces mean that digital technologies are now accessible for children at a very young age. But do children find digital technologies exciting for reasons beyond simple entertainment? The amount of digital technology available to my young daughters is massively different to that in my own childhood. As both a parent and a Social Worker, I've found it difficult to make sense of media reports and research findings in this controversial area. Is technology beneficial or detrimental to child development? Does screen time lead to increased distractibility, obesity and loneliness? Or does it offer opportunities for autonomy and experimentation beyond anything imagined when I was a young child? As the generation gap widens between adults and children’s' understanding of new technologies, how will we protect them from the risks while allowing them to benefit from the opportunities new technologies offer? In 2014 both Ofcom and the NSPCC (Jütte et al.) found that one in three children owned their own tablet. Figures published by the NSPCC also show smartphone ownership increasing with age (20 per cent of 8–11-year-olds and 65 per cent of 12–15-year-olds). These profound changes are reshaping children’s digital environment. The recent EU Kids Online Network project, called Zero to Eight, illustrates just how pervasive technology is becoming for younger children. The project report identified a significant increase over the previous five years of children under nine years old using the internet (Holloway et al., 2013). In particular it noted a growing trend for very young children (pre-schoolers) to use tablets and smartphones to access the internet:

Whilst children are now going online at a younger age, their ‘lack of technical, critical and social skills may pose [a greater] risk’ (Livingstone et al., 2011). The challenge for parents is how best to manage the risks alongside the benefits. I’ll get back to this later…

Children and Digital Technologies Children are often very engaged by digital technology. But why is it so compelling for young children to spend so much time interacting with their digital world? Firstly, technology is fun. Child-centred technology in particular is especially designed to be as entertaining and captivating as possible. Similarly, a big attraction of technology for children is that they see their parents and peers using it, and a major part of childhood is ‘modelling’ the behaviour of those around them, particularly parents: that is, children learn from observing and imitating others around them. Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory (SDT) seems particularly relevant to untangling the reasons behind young children’s fascination with the digital world. According to SDT, there are two overarching types of motivation, ‘intrinsic motivation’ and ‘extrinsic motivation’. The former refers to doing an activity for its own sake because it is enjoyable and this is thought to lead to persistence, good performance and overall satisfaction in carrying out activities. Ryan and Deci outline three basic psychological needs associated with intrinsic motivation that can be applied to children’s use of technology:

Although each of these three basic psychological needs may not be met for every child, the self-determination theory offers a good psychological basis for understanding children’s intrinsic motivation in using technology. According to one study, children are currently spending more time with technology than they do in school or with their families. Similarly, children as young as 2, 3 and 4 are playing with their parents’ phones or tablet devices; and some psychologists argue that this has an enormous impact on their brain development, as well as on their social, emotional and cognitive skills. This raises an important question: in this 24/7 digital world, should parents be setting new rules for their children’s engagement with technology? Should we be promoting new parenting classes for the modern age? Generational Divide The idea of a generational divide between children and adults has been a popular topic among psychologists and sociologists. This has resulted in the use of labels such as the ‘digital native’, the ‘net generation’, the ‘Google generation’ or the ‘millenials’, each of which highlights the importance of new technologies in defining the lives of young people. The most contentious term is the ‘digital native’. The term first appeared in an article by Marc Prensky to describe those children who spend much of their lives ‘online’, constantly ‘switched on’. It represents ‘native speakers’ who are ‘fluent in the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet’. There is a distinction between ‘digital natives’, who are those generally born after the 1980s and are technologically adept and comfortable in a world of technology, and ‘digital immigrants’, who are generally born before the 1980s and are fearful or less confident in using technology. To justify his claims Prensky draws on the widely held theory of neuroplasticity. This means that our brains are highly flexible and subject to change throughout life. The different neural connections in the brain change and evolve throughout childhood in response to the environment. It is claimed that young children’s brains now are developing differently to the way adults’ brains have developed, as children are growing up surrounded by new technologies. This topic of neuroplasticity is something that I have also covered in Risk, Resilience and Adoption. Safeguarding Many parents, teachers and Social Workers have legitimate reasons to worry about children’s engagement with the digital world. We know that children are likely to run risks if they access the internet unsupervised, or stay online for long periods of unbroken time. Examples of the apparent risks appear in the work of Howard-Jones, who analysed current research in neuroscience and psychology. He states that the developing brain can be susceptible to environmental influence, and digital technology opens it to risks including:

You can also find research into internet addiction, aggressive game-playing, grooming and bullying, which have also been linked to children’s exposure to the digital world. Social Media can also present problematic situations for adopted children, and those in foster placements or subject to child protection plans. Even the Pope waded in on the debate earlier this month, warning parents not to let children use computers in their bedrooms because of the 'dirty content' on the internet. Whether you are a digital optimist or pessimist, it’s obvious that while technology brings about opportunities, it also has associated risks. This has led to some professionals arguing that parents should limit young children’s use of, and exposure to, new digital technologies. But is this really the answer? Is simply restricting children’s access actually the best way to ensure their safety? Restricting access to technology may also restrict opportunities for children to develop resilience against future harm and I would argue that simply restricting access or removing technology from children’s lives seems inappropriate (except as a short term measure in cases where technology is presenting a significant risk of harm to the child). Perhaps we need to review parenting methods so we ensure sufficient levels of support for children growing up in this highly digital modern world. If we look at self-determination theory, the idea of giving children autonomy and choice to make appropriate decisions about their own digital world could be the answer. According to some, we need to trust in the maturity and judgement of children. We have to be able to trust their social skills in successfully negotiating these new ways of behaving and successfully managing or avoiding risks (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). It is important to recognise that children’s perceptions of problematic online situations may differ greatly from those of adults. Because of the different perceptions of adults and young people, and the lack of a neat distinction between positive and negative experiences online, many professionals opt to avoid the term ‘risk’, and prefer to talk about ‘problematic situations’. Research by Vandoninck and colleagues, based within the UK, tackles the idea of giving children autonomy to make their own choices. Awareness of online risks motivates children to concentrate on how to avoid problematic situations online, or prevent them from (re)occurring. This brings me to the concept of preventive measures – what children actually do or consider doing in order to avoid unpleasant or problematic situations online. Vandoninck and colleagues identified five main categories of measures discussed in the literature:

Perhaps the key focus of parents and professionals should be on helping children to acquire the knowledge and skills to moderate their own online behaviours; to develop resilience to risks and to become responsible digital citizens of the twenty-first century (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). For more information about safeguarding, take a look at my other posts on online safety and follow me on facebook and twitter. Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence. Today Edward Timpson, Children and Families Minister, addressed the NSPCC conference about how social work reform and innovation can help better protect vulnerable children. He became a Member of Parliament in 2008 after winning a by-election in the constituency of Crewe and Nantwich. In September 2012, he was appointed as a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Education, and following the 2015 general election, he was promoted to Minister of State for Children and Families.

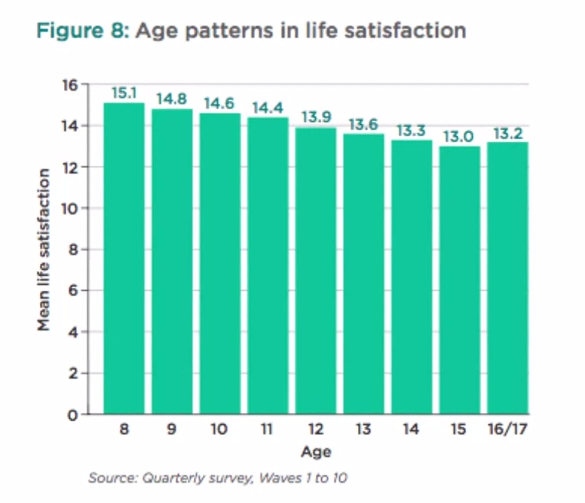

You can see the whole speech here, but I've summarised/quoted the main points below. He started his speech with a little self-deprecation, saying how thrilled and surprised he was to be back in office, before drawing attention to his own upbringing, in a household with adopted and fostered siblings, and his work with children in care. He says he believes “the protection of vulnerable children… [is] the most profound responsibility we have as a society". He said that during the last parliament he had worked to “strengthen the child protection system… with major reforms to social worker recruitment and assessment”. Also “the first independent children’s trust in Doncaster”, he claimed, are “freeing up local authorities so that they can set up new models of delivery”. Child sexual abuse and NSPCC report Referring to investigations in Rotherham, Rochdale and Oxford he said: “we’ve been able to shine a light on a police and social care system set up to protect children, but that all too often turned them away, leaving them in the hands of callous abusers”. He also said that “the Prime Minister has appointed Karen Bradley as a minister in the Home Office to tackle [CSE] alongside [him] - recognition that child sexual abuse is about child protection... but also about prosecution too”. Centre of Expertise Timpson reported that a “new Centre of Expertise” will try “to understand what works when it comes to tackling and preventing child sexual abuse”. In addition, he acknowledged “that while CSE is dominating the media, we must not lose sight of neglect”. That’s why, he said, they’re “looking at having a campaign to encourage the public to report all forms of child abuse and neglect”. Social work reform “At the heart of good child protection is, of course, good social workers”. He said that “the introduction of a new assessment and accreditation system for children’s social workers” will offer “a rigorous means of assuring the public that social workers…have the knowledge and skills needed to do the job”. His department will also continue to support “projects to bring the brightest and best into social work through Step Up to Social Work and Frontline”. Innovation programme Timpson said that he was “especially keen to see much closer working between the voluntary sector and local authorities - something the Children’s Social Care Innovation programme is encouraging and seeing take root.” There’s a “£1.2 million initiative with SCIE - The Social Care Institute for Excellence - that aims to help us learn better from serious case reviews (SCRs) and improve their quality, and which includes a pilot to improve how SCRs are commissioned”. There’s also a “£1 million funding for the NSPCC to introduce the New Orleans intervention model in south London - which aims to improve services for children under 5 who are in foster care because of maltreatment by promoting joint commissioning across children’s social work and CAMHS teams.” Character and resilience Timpson’s “brief has been extended to include character and resilience”, placing “a greater emphasis on helping children… develop the qualities and life skills that will give them a strong foundation for social life”. He told the audience of social care professionals that “there’s a need to get better and smarter about how we equip our sons and daughters with the attributes they need to find their feet today and truly flourish.” He concluded his speech by asserting that he is a “pragmatist and simply [wants] to do what’s best by and for children, wherever they are and whatever their circumstances.” Adolescence is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood and is a crucial developmental stage for our mental well-being. It is a period of physical, cognitive, social and emotional changes and it is important that adults supporting young people have a good grasp of the challenges they face. Physical changes in adolescence In 2013 The Good Childhood Report (The Childrens Society) charted the life satisfaction of a group of 8 to 17 year olds. They found that during this period life satisfaction declines. When it’s broken down the biggest drop seems to come from anxieties associated with physical appearance. Perhaps this isn't surprising considering that during puberty bodies’ change both in size and shape. Researchers have been debating a lot about whether and to what extent this may impact upon the body image and self-esteem of young people. While physical changes can be awkward for anyone, research suggests that adolescents who perceive their physical development as particularly early or late compared to their peers find it particularly difficult to adjust.

Brain development in adolescence While physical development can be quite obvious many parents and professionals are less aware that adolescence marks a period of profound cognitive development; a period of massive brain growth not seen since infancy. Recently research has been considering whether this can account for some of the common behaviours we see in teenagers: impulsivity, risk taking behaviours and intense emotions. Research has shown that it may have something to do with the pre-frontal cortex. In adults it is the part of the brain that helps us to maintain goal-directed behaviour, moderate intense emotional experiences and check our risky impulsive behaviour. Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence to indicate that purposive action selection depends critically on this particular region of the brain; however, it is also one of the last to develop. It is possible, therefore, that the risky and moody behaviour typically characteristic of this age group could have something to do with the late development of the pre-frontal cortex. Interpersonal relationships in adolescence Interpersonal development is a key stage in adolescence. It is a period of identify formation when young people become more oriented towards their peers, they individuate and separate, and become more autonomous from their family. Identity development correlates significantly with the quality of peer relationships, with their primary caregivers, and with any younger people who are around them. Interpersonal development is crucial in adolescence, and a lot of the psychological resilience and vulnerability manifest here. Transition points between primary and secondary school, residential moves or any other circumstance that forces the adolescent to re-establish themselves within a new peer group are absolutely key. A lot of their personal identity development is who they are to others, and often the most important people to a young person are their peers and who they are to other young people around them. We can also see a high level of compartmentalization in adolescent social circles. That is to say, adolescents can often be somebody completely different to their families, to who they are to friends, to who they are at extra-curricular activities. That is one of the reasons why the quality of a young persons relationships and their social environment is so important and why experiences, such as bullying or social isolation, can have such a profound impact on a young person's mental health and well-being. One of the things that comes with emerging independence, and with individuating as a young person, is the formation of different bonds and different types of relationships. Indeed, the emergence of romantic relationships, and active and romantic feelings, are crucial. This is why it is important that young people have positive and healthy experiences. They are very vulnerable to exploitation and negative experiences which, again, can have a profound effect on their mental health and well-being. Young people tend to experiment a lot with intimate relationships, with romantic relationships, and different types of peer relationships. Sometimes it can be difficult for young people, when identities aren't fully formed and they are less clear about who they are to others, to know how to define these – are they a boyfriend/girlfriend, friend, sporting team mate? These difficulties and uncertainties can make them increasingly vulnerable in relationships where there is a disparity of power. Traditionally adolescence has been discussed and defined as a period of storm and stress. We expect high levels of conflict experimentation; a lot of adolescent identity development is in opposition to what is expected of them. Adolescents can be inter-personally challenging and difficult both within their families, within institutions, and any other contexts that they may find themselves in. They usually struggle with ideas of identity, conformity, and indifference. It is intensely difficult for young people to appreciate how they're perceived by others yet, at the same time, it's also very important to them. Adolescent development waxes and wanes, they can go from moratorium and uncertainty to premature identity formations. It is, therefore, important for parents, carers and professionals to consider these dynamic stages, as premature pinning of expectations can be quite detrimental. Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

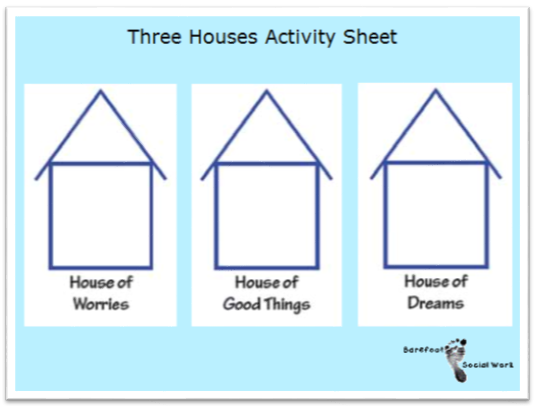

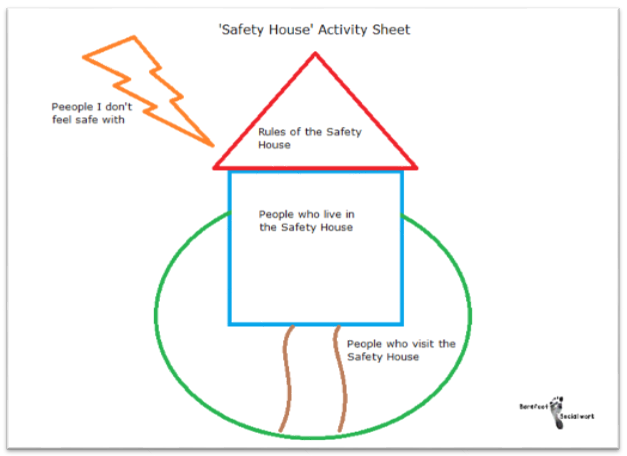

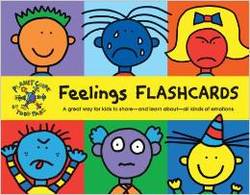

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.  The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred” system was for social workers to have the time and the skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. NICE has also recommended that professionals take greater steps to actively involve children and young people in the process of entering care, changing placement, or returning home and a series of intervention tools should be considered to help guide decisions on interventions for children and young people. What this means is that there is a general consensus that there should be a greater focus on direct work in professional practice. Direct work with children is a complex skill to master but the techniques can be relatively simple. Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective in the past. In most cases all you need is pen, paper and time. The 'Three Houses' technique was created by Nicki Weld and Maggie Greening in New Zealand (Weld 2008, cited by Turnell 2012) and is mentioned in the Munro review. It helps a child or family think about and discuss risks, strengths, and hopes. It is usually most effective with older children or with families where you are finding it difficult to devise an effective intervention plan and can be used with individuals or a group. Taking three diagrams of houses in a row, Social Workers explore the three key assessment questions: 1) What are we worried about, 2) What’s working well and 3) What needs to happen/how would things look in a perfect world. Start by presenting the three blank houses to the child or they could draw their own. Beginning with the ‘House of Good Things’, the child is asked what the best things are about living in the house and questioning is directed around positive things that the child enjoys doing there. After this stage you should progress to discuss the ‘House of Worries’ and find out if there are things that worry the child in the house or things that they don’t like. Finally the ‘House of Dreams’ covers an exploration of thoughts and ideas the child has about how the house would be if it was just the way they wanted it to be. A description is built up detailing who would be present and what types of behaviours would occur. The ‘Safety House’ tool was developed by Sonja Parker. It helps to represent and communicate how safe a child feels in their own home and what could be done to improve things. It can be used with children who are not currently living with parents in order to plan for reunification. Progress can also be assessed by changes in the safety house drawing and can be a key tool in the assessment of risk and safety planning. Start with a picture of a house with a roof, path and garden. The house and garden are divided into sections and the child can describe who they would like to live with them, who can visit and stay over and who is not allowed to come into the house. Safety rules are devised and put into the roof of the house and details of what happens in the house and what people do can be discussed. The house can also be utilised as a readiness scale by using the path as an indicator of how ready they are to return home.  The faces technique involves asking the child to pick from a range of different facial expressions and assigning them to members of their family. It is a useful method for discovering how a child perceives their family and is likely to appeal to younger children or those at an earlier stage of development. After explaining to the child that you want to know more about their family, show them some pictures of different facial expressions, making sure they understand each expression and the emotion it relates to. You could draw them yourself or use a professional set. I recommend the Todd Parr Feelings Flash Cards which are really attractive and accessible for young children. They’re also thick, sturdy and, most importantly, durable. For more developed children, you can select a wide range of expressions; for those at earlier stages of development, you might want to just use two or three (ie happy, sad and angry). There are many other activities that are effective in direct work with children and young people. I will try to write more posts soon. Follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss them! In the meantime, you might like to take a look at Audrey Tate’s book, Direct Work with Vulnerable Children. It’s primarily a set of playful activities to create opportunities to engage children. Through these activities children are enabled to tell their stories and provide Social Workers with assessment and support opportunities. The Joseph Rowtree Foundation estimates that by 2020 one in four families will be in relative poverty as a result of welfare reform. If we accept that poverty can be a causal factor of adverse childhood experiences then we can assume that this will have a huge impact on the health, social and economic well-being of a whole generation of children and young people. However, this increase in poverty also comes at a time when local authority services are being hit by budget cuts and it is becoming increasingly difficult for children’s social work to act preventively. When children are at risk of significant harm they should, of course, be removed but we can’t hide from the reality that outcomes for children in care are on average markedly worse than for those who are not. Take a look at the meta-analysis data I discussed in my post risk, resilience and adoption and you will see that a solely reactive approach is very short sighted. The real focus should therefore be on improving the quality and timeliness of the interventions so that we can prevent children from becoming at risk of significant harm in the first place.

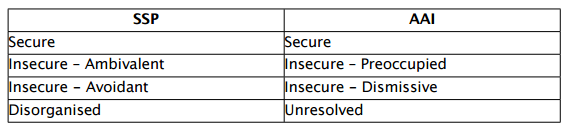

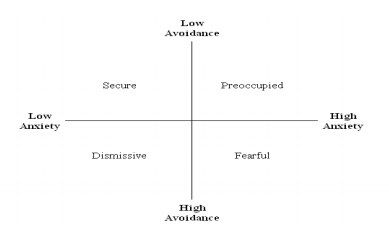

So, what can be done if the current government remains committed to further cuts and austerity? In April 2015 a report ‘Breaking The Lock’ was published, exploring the challenges faced by children’s services. The report argues there is a disconnect between Ofsted and local government and evidences a new model for children’s services that, they claim, is both financially sustainable and improves life chances for children. It proposes a new model that places the emphasis on prevention and early intervention. It also explains what this model could look like from an operational perspective, stressing the importance of integration and multi-agency working. In reaching its recommendations the report highlights what it sees as four fundamental problems: Firstly, the impact of the single word judgement ‘inadequate’ from Ofsted can have a catastrophic spiralling effect on a local authority, turning a poorly performing authority into a broken one. In March, Alan Wood, president of the Association of Directors of Children’s Services, told PSE “We believe this framework does not get to the heart of how well services are working, and, with a single worded judgement it tells a partial and excessively negative story, which runs the risk of weakening the very services it seeks to improve.” Secondly, the ‘rise in family breakdown as a leading cause of children needing support’ is exposing fundamental weaknesses in the current model of children’s services and a lack of early intervention is allowing manageable problems to descend into acute crisis. Thirdly, there is national shortage of social workers meaning that struggling councils are overly reliant on agency staff costing more money and leading to less consistency of support for vulnerable children. I would argue that it is actually a case of too few experienced social workers that is the problem, and agency workers are being used to fill these knowledge gaps on local authority teams. Findings from the social work reform board show how burnout rates are high meaning that local authorities are losing newly qualified social workers very quickly. Whilst it is great that Frontline has focussed on drawing high quality candidates into the profession, the government also needs to focus on retention. I suspect that their current plans to jail social workers who fail to prevent neglect, despite the necessary infrastructure to properly address it will only exacerbate the problem. Finally, the report argued that children’s services and Ofsted need to collaboratively modernise to reflect the reality of the public sector’s financial climate and the growing complexity of needs that vulnerable families have. These times of austerity will undoubtedly require local authorities to control resources more effectively and be more creative about using what resources are available through close liaison with multi-agency partners. There is also a clear economic logic for the region to come together to pool risks and share financial resources. The Greater Manchester devolution deal, for instance, will give the city region more devolved powers than anywhere else in England, London included. Anyone wanting to hear if devolution in Greater Manchester could address our multiple and worsening inequalities should look into attending this event at Manchester Business School on the 6 July 2015. Yesterday I posted about the origins of attachment theory. Draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argue that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. My personal experience of the Social Work Masters was that attachment was covered but in a rather one dimensional manner without the necessary critical analysis. In recent years, some assumptions have been challenged and this post will look at three of the main debates in the theories of attachment. These debates are ongoing and you will have to judge for yourselves. Adult attachment styles are dictated by the mother-child relationship. This assumption rests on the principle of monotropy, but recent reconceptualisations of attachment suggest that attachment might be more significantly influenced by multiple caregivers and relationships. There are three possible models: Firstly, the Hierarchical model is the classic understanding of attachment theory, in which attachment is to a primary caregiver (the mother) and that this relationship is concordant with other attachment relationships, and mediates future relationships. This model derives from Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s research. Secondly, the Integrative model describes an alternative organisational structure in which the child integrates all of his/her attachment relationships into a single representation. In this model, by Van IJzendoorn et al. (1992) they suggest that all attachment relationships are equal and independent, and the quality of the combined relationships best predicts his/her developmental consequences. The entire extended network of attachments is a better predictor of attachment than family attachment style only. Thirdly, the Independent model states that each attachment relationship brings an independent representation with qualitative differences, domain and person specific. For example, the child’s relationship with peers is more likely to be determined by the maternal attachment, whilst social competence, efficacy and adjustment is more likely to be determined by paternal attachment. The evidence for this model is less well-established, but Crittenden’s Dynamic Maturational Model uses a version of this as its basis (more on that later). There is evidence, both for and against these models using cross-cultural studies, studies of attachment in adolescence, and inter-generational studies. It's probably too much to cover right now but I may cover it in another post at a later date. A categorical classification system is the most accurate way to describe attachment styles. The two most significant attachment measures are the Strange Situation Protocol, used with toddlers, and the Adult Attachment Interview. Both allocate individuals to one of four categories. If you’re interested in finding out more about your own attachment style you might like to look at this online version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale, a test of attachment style. The ECR was created in 1998 by Kelly Brennan, Catherine Clark and Philip Shaver. It groups people into four different categories on the basis of scores along two scales. The inventory consists of thirty six that must be rated on how characteristic they are of you. If you do complete the above questionnaire, you will be given a classification made on the basis of a dimensional conceptualisation of attachment, that looks like the one below. Fraley & Spieker (2003) have argued that this provides a more sensitive and ecologically valid assessment of individual attachment style. Finally, Patricia Crittenden has elaborated further by creating a model of attachment called the Dynamic Maturational Model. Crittenden’s model assumes multiple frames of reference and context-dependent responses, centred around a cluster of sub-categories. So, instead of the individual being categorised, the individual has a set of strategies, which can be matched to a range on this sphere. She adheres very strongly to an evolutionary framework. To see an overview of her theory, take a look at this YouTube video where she gives a presentation, titled "The development of protective attachment strategies across the lifespan", at the BPS DCP Annual Conference in 2012: Attachment style is set by 12-18 months

Bowlby’s original theory implied, partly by its focus on a single caregiver, that attachment style might be set quite early on, although he explicitly allowed for life events and circumstances to allow change. However, it was Ainsworth’s development of the Strange Situation Protocol that really reinforced the idea that attachment style is set by the time of primary individuation at or around 18 months. There is evidence to support this stability of attachment style, but it is not black and white. Different studies have found that:

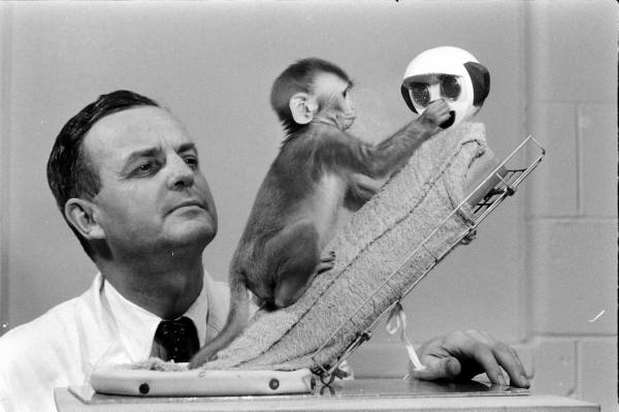

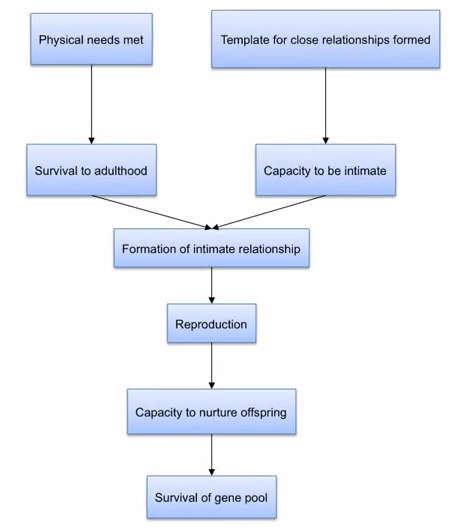

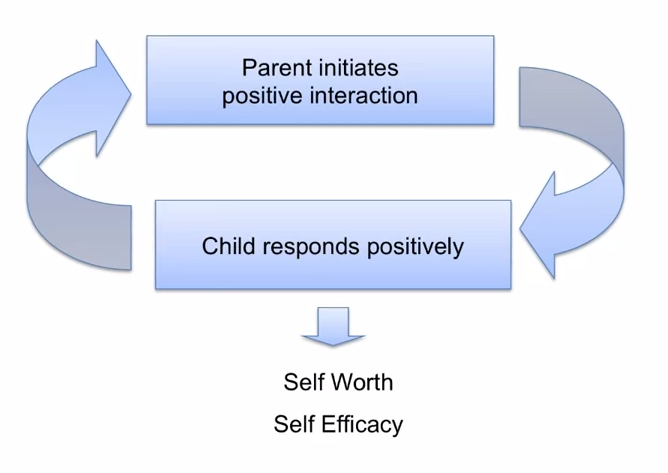

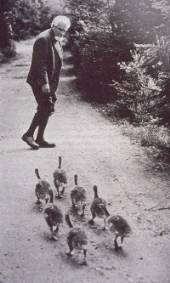

So, attachment classification certainly has predictive power, but not 100%. In adoption studies (See my previous post on Risk, Resilience and Adoption), children adopted before 12 months of age are only slightly more likely to be insecurely attached than children raised in birth families, whilst children adopted after 12 months are at significantly higher risk of insecure attachment, and disorganised attachment specifically. There are many, many more debates around theories of attachment. Too many to cover in a short blog post. However, I hope this has given you a tiny introduction to current thinking around the topic. It is important that practitioners are aware of these issues so that they can assess for themselves how best to integrate them into practice. Unfortunately, I can't give you a definitive answer about which theory or approach is best. You'll need to make an educated judgement based upon your own knowledge, research and professional experience. All social workers in the care system should be trained in recognising and assessing attachment, according to proposed guidelines. The draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argues that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. I couldn't agree more and I'm a little disappointed that this isn't already the case. This post, covering the origins of attachment theory, will be the first in a short series on attachment and it's implications for social work practice. Attachment theory is almost 75 years old. During this time, some elements have changed but the underlying principles remain as true now as then. In the 1940s and 50s John Bowlby worked with children who had been either separated from their parents as war orphans or evacuees or who had experienced significant adversity in their early life. He believed that these children went on to experience a range of emotional, behavioural and psychological difficulties as a result of their early experiences of loss and trauma. Bowlby has been criticised for developing a normative theory of development based on non-normative experiences. He was trained in a psychoanalytic tradition, but was disillusioned by its intrapersonal focus; instead he was influenced by the important empirical discoveries happening around the same time. I’ll outline some of them below: In his 1943 book, The Nature of Explanation, Kenneth Craik described the central nervous system as “a calculating machine capable of modelling or paralleling external events” and saw this as a basic feature of thought. He described the human or animal in this way: This might seem obvious to us now but to John Bowlby it provided a pragmatic explanation to the adverse developmental outcomes he had seen in orphans and institutionalised children; more so than the psychoanalytic training of his background because Craik’s theory was outward looking; seeing the individual in context. John Piaget described intellectual development as a process of adjustment and adaptation to the world. As part of this growth children have to go through a process of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation involves the inclusion of new information into existing schema or internal working models. Accommodation happens when a child is not able to assimilate information into an existing schema and either has to change the schema or develop a new one. Craik and Piaget were important for attachment theory because they explained how infants develop schemas or maps for future relationships based on prior experiences and learning.  Niko Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz were ethologists studying the sociology of birds. Their careers travelled in parallel, influencing each other along the way. Lorenz was inspired to conduct a study involving goslings which ultimately led to the imprinting hypothesis. In this study Lorenz split a large hatch of goslings, leaving half with the mother and taking the other half and raising them himself. Over the course of their development the goslings quickly identified him as their primary attachment figure and followed him, copying his behaviour. He taught them to swim, he used to call them with a special horn for feeding time and they always followed him. When they were given the opportunity to return to their birth mother, they didn’t recognise her as such, instead preferring Lorenz. This taught us about the importance and probable biological nature of the bond between mother* and offspring, in which the mother, the primary attachment figure, is the one who provides physical and emotional care and nurture. As a light break, you might enjoy the following Tom & Jerry cartoon where they, in a very flippant and simplified manner, explain the concept of imprinting. Later, in the 1960s Harry Harlow carried out a series of lab based experiments on monkeys (seen at the top of this post), rearing them in total social isolation. The study, which was unquestionably cruel, showed that monkeys were preferentially seeking out a cloth mother for nurturing; spending up to 18 hours a day holding onto her and seeking out a wire mother only for food. All the means for a healthy development were available and yet the monkey showed severe damage as a result of their experiences. The study suggested that mammals need reciprocal nurturing and attachment as much as they need their physical needs met. Bowlby hypothesised that since humans cannot survive without adult care our evolutionary history has selected pre-wired dispositions on both the part of the adult and the child that ensure human survival. From this basis, Bowlby developed a model of attachment that is monotropic (has a single attachment figure). It’s focussed on survival of the individual and the species and is integrated with human development to both influence broader developmental outcomes and be influenced by individual and contextual factors. Within this model tasks are identified for care giver and child that promote reciprocity and ultimately autonomy. The goal is to maintain emotional and physical equilibrium of the child thus keeping their attachment systems settled, allowing exploration and learning. During periods of distress the attachment system is activated and takes priority over the exploratory system. The regulation of emotion and behaviour are tasks that the care giver and child accomplish together through reliable, responsive and consistent care giving. The care giver provides the infant with the necessary up-regulation and down-regulation that the infant needs. Consequently, parents that are not attuned to the infants needs, and cannot reliably and consistently provide care, leave the child without the necessary external regulatory support. Over time this develops into a complex system which affects the way in which a child, and eventually adult, responds to their own needs and to those other others.

I hope you've found this post interesting. You might also be interested in my post on Attachment Based Family Therapy. I'll write more on the current debates in attachment and methods of assessment soon. Follow me on facebook and twitter so you don't miss them. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|