|

In 2010/11 Professor Eileen Munro reviewed the English children’s services system and found organizations and workers had become over-bureaucratized and compliance driven at the expense of direct work with families, parents and children. Following the recommendations of the Munro review, the UK government launched a Children’s Services Innovations programme which, amongst other things, has financed the development of a new app for social workers to use in their practice with children and families. Developed in Western Australia and designed with children’s services practitioners in UK, USA and Australia, the My Three Houses App offers a tool that taps into children’s love of all things iPad and encourages them to speak about what is happening in their life. The three houses tool was first conceived in New Zealand in 2003 and since then has been used by social workers all over the globe to place the voice of the child at the centre of child protection assessment and planning. I've blogged about using the analogue version here. This app brings the tool into the digital realm. There's video... Interactive animation... and a drawing pad for children.

0 Comments

As part of my research I have been looking at the construction of parenting and, specifically, mothering. How expectations of the parenting role has changed over time and how this has shaped and been shaped by government policy and legislation. I'm going to try and blog about pieces that I think will be particularly interesting to Social Workers, as I know quite a few of you follow my page, but I'll try not to bombard you too much with academic content.

Today I read The Social Work Assessment of Parenting: An Exploration by Johanna Woodcock. Although it was published in the British Journal of Social Work over a decade ago (2003) I believe her findings are still relevant today and would be a good read for any practitioner wanting to reflect upon their own construction of parenting and practice. Woodcock’s paper draws on a qualitative study of Social Workers conceptualisations of parenting and the relationship this construction has with practice. Within her exploratory study, Social Workers were asked to describe and give their opinions on the parenting that occurred within a case that they brought forward. Analysis of the data she obtained revealed four types of expectations that underlay judgements of parenting deemed both ‘good enough’ and ‘not good enough’. 1. The expectation to prevent harm. Woodcock found that Social Workers were influenced by legal or quasi legal constructions of parenting. Their overriding concern was the capacity of the parent to prevent harm and relied upon the presence or absence of evidence of ‘physical abuse’ ‘emotional abuse’, ‘sexual abuse’ or neglect in making this judgement. 2. The expectation to know and be able to meet appropriate developmental levels. Woodcock found that Social Workers attributed a parent’s failure to protect their child from harm to their limited understanding of their child’s stages of development. Woodcock highlighted the narrative from one case where a parent and social worker were unable to agree on the level of appropriate supervision. A second area of Social Worker concern manifested when a delay in growth and development was deemed to be the result of poor parenting. 3. The expectation to provide routinised and consistent physical care. Parents were expected to appreciate the importance of routines and demonstrate their capacity to carry them out Woodcock found that routines were a key element of Social Work discourse. ‘Not meeting the child’s needs’ invariably referred to a lack of routine and consistency and that the child’s emotional needs for a sense of safety and security were not being met. 4. The expectation to be emotionally available and sensitive. For some Social Workers it was insufficient for a parent to simply love a child. They needed to have more insight into the emotional reasons for a child’s behaviour, which took them beyond physical care and to demonstrate a level of affect and interest in the parent-child interaction. Woodcock also looked at the Social Workers’ ‘psychological appreciation’ of the parent. She found that one way in which social workers made sense of problem parenting involved whether the parent was psychologically ‘damaged’ or ‘disturbed’ through abuse, or a lack of consistency or emotional warmth in their own childhood. Alternatively, early experiences were seen to provide modelling for future parenting and the absence of a positive role model accounted for their lack of ‘knowledge'. Importantly, Woodcock noted that these explanations draw on two implicit competing theoretical orientations: psychoanalysis and social learning theory; and despite being assimilated into assessment this evidence base was not evident in intervention or treatment. Conversely, Social Workers relied on exhorting parents to change or ‘getting them’ to take responsibility. She found little evidence of attempts through intervention to address these deeply ingrained psychological needs, either through direct social work or referral to psychological services. When psychologists were called upon it was to contribute an opinion with regard to the parent’s capacity to change rather than to help facilitate that change. Woodcock asserted that it was this incoherence between the intervention strategy and the social workers construction of parenting which inevitably led to resistance. Somewhat ironically, it is also resistance and an ‘inability to work with agencies’ that compounds an assessment of poor parenting. The main concern for practitioners should be Woodcock’s identification of a ‘surface static’ notion of parenting. A surface response means that the psychological factors underlying parenting problems remain unresolved. By relying on exhortation to change, rather than responses informed by psychological observations, Social Workers create an environment that is unconducive to change and thus perceptions of parent ‘resistance’ more likely. An explanation offered by Woodcock for the presence of a ‘surface-static model’ is the fact Social Workers are increasingly directed to their legal responsibilities to ensure the protection of the child from harm, rather than on problems that beset the parent. This professional quandary has, in my opinion, only worsened in the intervening decade and is something that government needs to address if outcomes are to improve. Social Workers need to reject the current political rhetoric surrounding parenting which places responsibility for child outcomes with parents, whilst underplaying socio-economic factors. On a practice level, Social Workers can consider what constructs they being to an assessment and whether their work reinforces a static notion of parenting. Try and incorporate these questions into your reflective practice: Am I focussing solely on assessment and parental behaviour, or am I actively seeking to enhance parental capacity through improvements in the problems that beset the parent. I imagine this would be an interesting discussion in supervision.

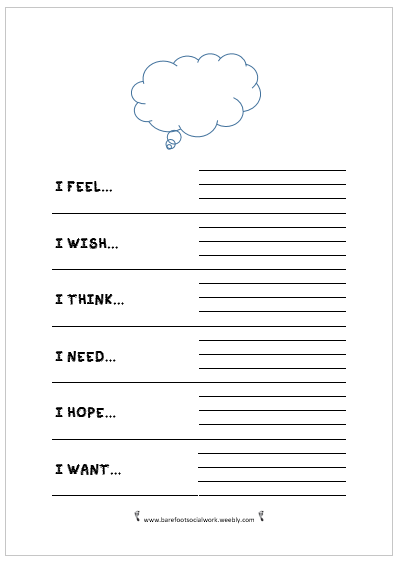

I've just added a new assessment exercise to the tools section of my website. It's pretty self explanatory. It can be self completed by a client, or during an assessment session, to establish what they want to change, achieve or work towards. It would compliment a motivational interviewing approach which you can check out in my previous post here. Let me know if you use it! :-)

Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

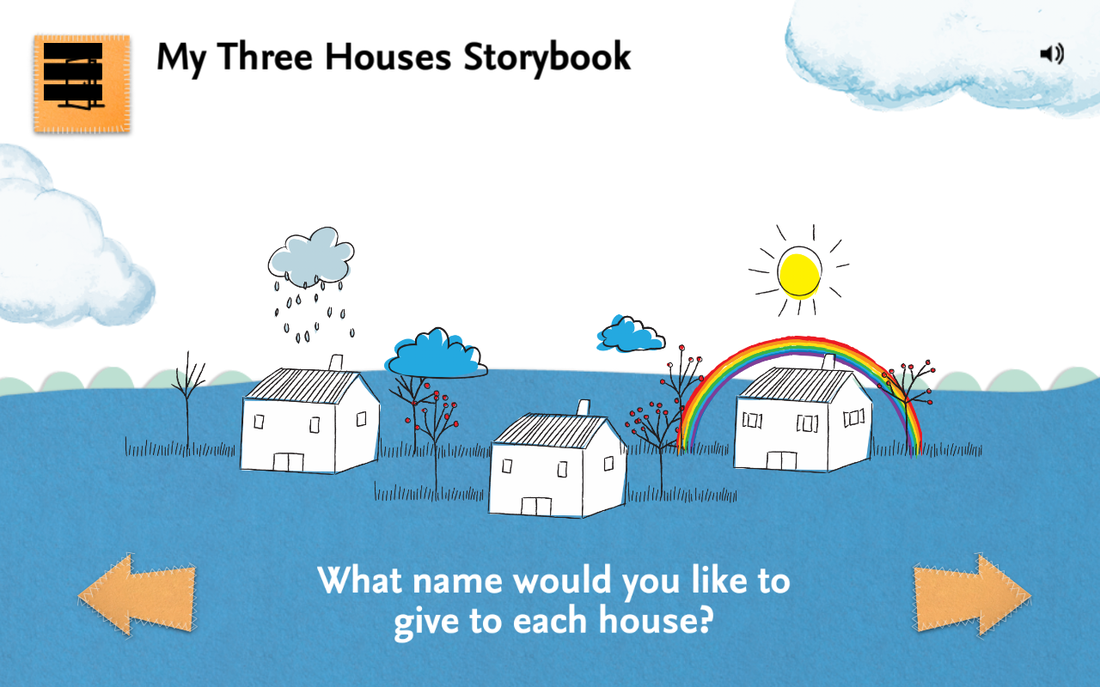

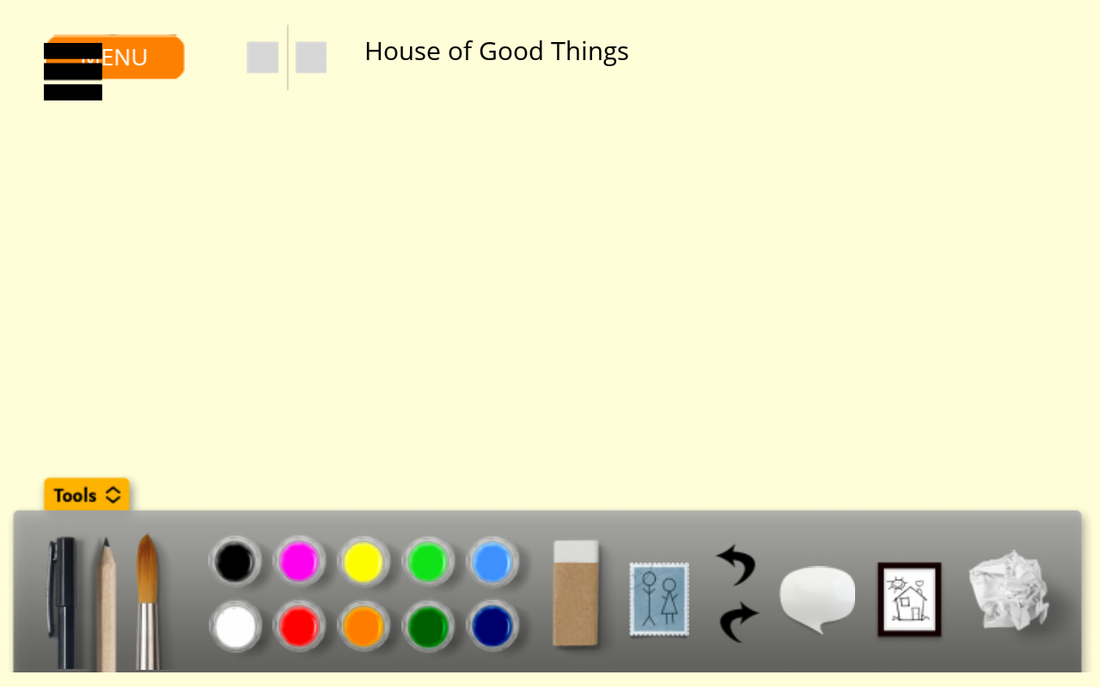

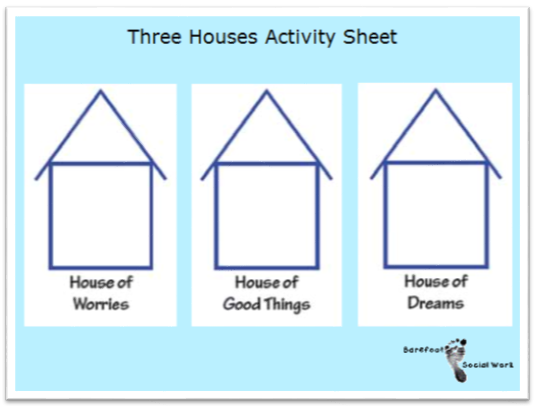

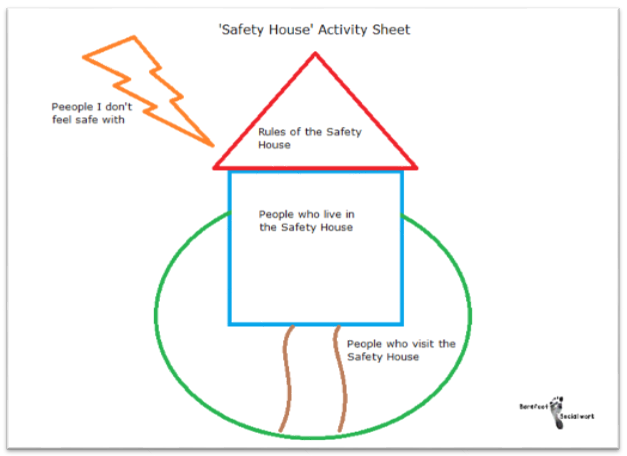

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.  The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred” system was for social workers to have the time and the skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. NICE has also recommended that professionals take greater steps to actively involve children and young people in the process of entering care, changing placement, or returning home and a series of intervention tools should be considered to help guide decisions on interventions for children and young people. What this means is that there is a general consensus that there should be a greater focus on direct work in professional practice. Direct work with children is a complex skill to master but the techniques can be relatively simple. Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective in the past. In most cases all you need is pen, paper and time. The 'Three Houses' technique was created by Nicki Weld and Maggie Greening in New Zealand (Weld 2008, cited by Turnell 2012) and is mentioned in the Munro review. It helps a child or family think about and discuss risks, strengths, and hopes. It is usually most effective with older children or with families where you are finding it difficult to devise an effective intervention plan and can be used with individuals or a group. Taking three diagrams of houses in a row, Social Workers explore the three key assessment questions: 1) What are we worried about, 2) What’s working well and 3) What needs to happen/how would things look in a perfect world. Start by presenting the three blank houses to the child or they could draw their own. Beginning with the ‘House of Good Things’, the child is asked what the best things are about living in the house and questioning is directed around positive things that the child enjoys doing there. After this stage you should progress to discuss the ‘House of Worries’ and find out if there are things that worry the child in the house or things that they don’t like. Finally the ‘House of Dreams’ covers an exploration of thoughts and ideas the child has about how the house would be if it was just the way they wanted it to be. A description is built up detailing who would be present and what types of behaviours would occur. The ‘Safety House’ tool was developed by Sonja Parker. It helps to represent and communicate how safe a child feels in their own home and what could be done to improve things. It can be used with children who are not currently living with parents in order to plan for reunification. Progress can also be assessed by changes in the safety house drawing and can be a key tool in the assessment of risk and safety planning. Start with a picture of a house with a roof, path and garden. The house and garden are divided into sections and the child can describe who they would like to live with them, who can visit and stay over and who is not allowed to come into the house. Safety rules are devised and put into the roof of the house and details of what happens in the house and what people do can be discussed. The house can also be utilised as a readiness scale by using the path as an indicator of how ready they are to return home.  The faces technique involves asking the child to pick from a range of different facial expressions and assigning them to members of their family. It is a useful method for discovering how a child perceives their family and is likely to appeal to younger children or those at an earlier stage of development. After explaining to the child that you want to know more about their family, show them some pictures of different facial expressions, making sure they understand each expression and the emotion it relates to. You could draw them yourself or use a professional set. I recommend the Todd Parr Feelings Flash Cards which are really attractive and accessible for young children. They’re also thick, sturdy and, most importantly, durable. For more developed children, you can select a wide range of expressions; for those at earlier stages of development, you might want to just use two or three (ie happy, sad and angry). There are many other activities that are effective in direct work with children and young people. I will try to write more posts soon. Follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss them! In the meantime, you might like to take a look at Audrey Tate’s book, Direct Work with Vulnerable Children. It’s primarily a set of playful activities to create opportunities to engage children. Through these activities children are enabled to tell their stories and provide Social Workers with assessment and support opportunities. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|