|

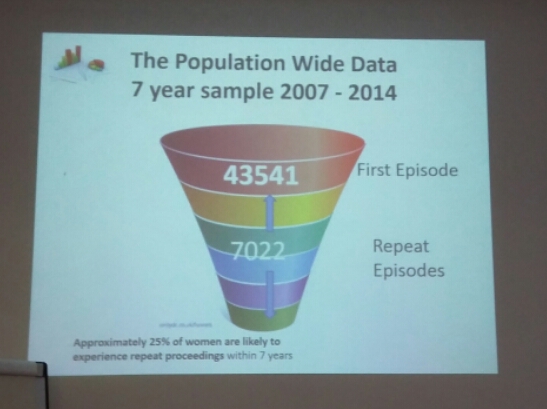

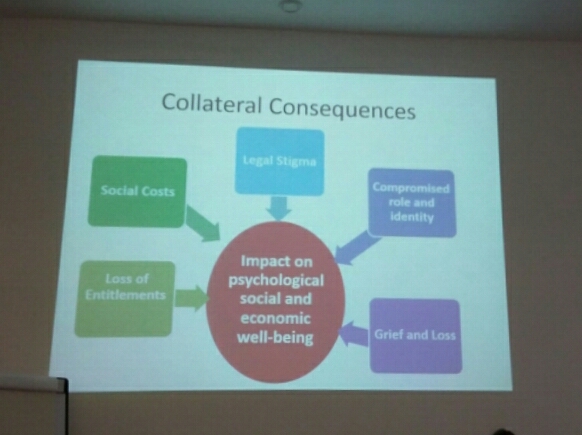

Yesterday I attended ‘Parents’ Voices and their Experiences of Services’ at Friends Meeting House in Manchester. It was an opportunity to examine priorities for system, policy and practice change, drawing upon findings from research and was a very valuable day for reflective practice. The event began with a short introduction by Safeguarding Survivor who chaired the conference with great confidence and professionalism. I know she was nervous but you couldn't tell and she did a brilliant job. If you aren't aware of her story, I recommend you read her blog. It offers great insight into the child protection system from a parents’ perspective and provides excellent advice for others whose children have been identified as ‘at risk’. Her work has been praised for its balance and value by Sir James Munby and you will soon be able to read more of her case after the court granted Louise Tickle (a freelance journalist) permission to publish details in a broadsheet newspaper. You can read the judgement at Family Law.  Siobhann and three mothers from The Mothers Apart project (Women Centre) Kirklees spoke about their book In Our Hearts. It presents open and honest accounts of initial separation, court proceedings, relationships with services, of mothers who have been able to have children returned to their care or contact increased, mothers who have no current contact at all and those for whom contact remains limited. It offers itself up as an aid and guide to learning for parents, families and professionals working in pursuit of child protection. As a result of co-production learning Mothers Apart have developed women centred working that recognises people as assets. Whilst every woman is different they have found that there are a number of common themes and, consequently, much of their work is about power. Sean Haresnape (Principal Social Work Advisor) from Family Rights Group outlined a Parents Charter being developed in collaboration with parents and professionals, that sets out expectations of how services should engage with parents, whose children are subject to statutory interventions; and we heard from Declan, a father and care leaver who had his daughter placed with him following care proceedings. Prof. Karen Broadhurst (Lancaster University) and Claire Mason (ISW & Lancaster University) presented preliminary findings from their 2 year study of birth mothers, their partners and children, within recurrent care proceedings under s.31 of the Children Act in England. The project hopes to confirm the national scale and pattern of recurrent proceedings together with the characteristics and service histories of parents caught up in this cycle. Statistical methods have been used to quantify recurrence and examine the relationship between recurrence and key explanatory variables. This has been complemented by qualitative components that include in-depth interview work with birth mothers in five local authority areas and in-depth profiling of a subset of randomly selected case files. Through data mining they have found that 25% of women who have been through care proceedings will return within 7 years. Teenage motherhood is associated with a significant number of repeat care proceedings and Prof. Broadhurst questions whether the family court is the most appropriate setting for dealing with teenage parents. Another facet of their research looks at the collateral consequences of care proceedings and asks who, once a court case has concluded, is there to support parents with the psychological, social and economic consequences of losing a child. Whilst the child and adopters/foster carers remain supported for a time by Social Workers and other services, there are no statutory support available to parents. This short-sighted approach demonstrates a lack of understanding of the collateral consequences and their cumulative impact which can drive women in to unhealthy relationships and successive pregnancies. In subsequent cases Local Authorities and Courts have been found to act more swiftly and are more likely to remove closer to birth, with adoption being the most likely outcome, compounding the cycle.

Similar concerns were raised last week by Sir James Munby when I attended the annual Family Justice Council debate in London. He said that it was “not fair on subsequent children that post adoption support isn't provided to birth parents” and “there is some substance to the question whether resources are adequately balanced between support for adoption and support for families”. Finally, Prof. Kate Morris (Sheffield University) outlined the empirical research she and Prof. Brid Featherstone (University of Huddersfield) are conducting as part of Your Family Your Voice – an alliance of families and practitioners working to transform the system. Their work, looking at family experiences of multiple service use, highlights the profound difficulty families often find navigating their way through services. At the end of the presentations we were asked to reflect upon what we had heard and identify what changes could be made to make the system a more humane one and minimise trauma for parents, children, their families – and also for practitioners. I invite you to do the same and participate in the research here.

1 Comment

As part of my research I have been looking at the construction of parenting and, specifically, mothering. How expectations of the parenting role has changed over time and how this has shaped and been shaped by government policy and legislation. I'm going to try and blog about pieces that I think will be particularly interesting to Social Workers, as I know quite a few of you follow my page, but I'll try not to bombard you too much with academic content.

Today I read The Social Work Assessment of Parenting: An Exploration by Johanna Woodcock. Although it was published in the British Journal of Social Work over a decade ago (2003) I believe her findings are still relevant today and would be a good read for any practitioner wanting to reflect upon their own construction of parenting and practice. Woodcock’s paper draws on a qualitative study of Social Workers conceptualisations of parenting and the relationship this construction has with practice. Within her exploratory study, Social Workers were asked to describe and give their opinions on the parenting that occurred within a case that they brought forward. Analysis of the data she obtained revealed four types of expectations that underlay judgements of parenting deemed both ‘good enough’ and ‘not good enough’. 1. The expectation to prevent harm. Woodcock found that Social Workers were influenced by legal or quasi legal constructions of parenting. Their overriding concern was the capacity of the parent to prevent harm and relied upon the presence or absence of evidence of ‘physical abuse’ ‘emotional abuse’, ‘sexual abuse’ or neglect in making this judgement. 2. The expectation to know and be able to meet appropriate developmental levels. Woodcock found that Social Workers attributed a parent’s failure to protect their child from harm to their limited understanding of their child’s stages of development. Woodcock highlighted the narrative from one case where a parent and social worker were unable to agree on the level of appropriate supervision. A second area of Social Worker concern manifested when a delay in growth and development was deemed to be the result of poor parenting. 3. The expectation to provide routinised and consistent physical care. Parents were expected to appreciate the importance of routines and demonstrate their capacity to carry them out Woodcock found that routines were a key element of Social Work discourse. ‘Not meeting the child’s needs’ invariably referred to a lack of routine and consistency and that the child’s emotional needs for a sense of safety and security were not being met. 4. The expectation to be emotionally available and sensitive. For some Social Workers it was insufficient for a parent to simply love a child. They needed to have more insight into the emotional reasons for a child’s behaviour, which took them beyond physical care and to demonstrate a level of affect and interest in the parent-child interaction. Woodcock also looked at the Social Workers’ ‘psychological appreciation’ of the parent. She found that one way in which social workers made sense of problem parenting involved whether the parent was psychologically ‘damaged’ or ‘disturbed’ through abuse, or a lack of consistency or emotional warmth in their own childhood. Alternatively, early experiences were seen to provide modelling for future parenting and the absence of a positive role model accounted for their lack of ‘knowledge'. Importantly, Woodcock noted that these explanations draw on two implicit competing theoretical orientations: psychoanalysis and social learning theory; and despite being assimilated into assessment this evidence base was not evident in intervention or treatment. Conversely, Social Workers relied on exhorting parents to change or ‘getting them’ to take responsibility. She found little evidence of attempts through intervention to address these deeply ingrained psychological needs, either through direct social work or referral to psychological services. When psychologists were called upon it was to contribute an opinion with regard to the parent’s capacity to change rather than to help facilitate that change. Woodcock asserted that it was this incoherence between the intervention strategy and the social workers construction of parenting which inevitably led to resistance. Somewhat ironically, it is also resistance and an ‘inability to work with agencies’ that compounds an assessment of poor parenting. The main concern for practitioners should be Woodcock’s identification of a ‘surface static’ notion of parenting. A surface response means that the psychological factors underlying parenting problems remain unresolved. By relying on exhortation to change, rather than responses informed by psychological observations, Social Workers create an environment that is unconducive to change and thus perceptions of parent ‘resistance’ more likely. An explanation offered by Woodcock for the presence of a ‘surface-static model’ is the fact Social Workers are increasingly directed to their legal responsibilities to ensure the protection of the child from harm, rather than on problems that beset the parent. This professional quandary has, in my opinion, only worsened in the intervening decade and is something that government needs to address if outcomes are to improve. Social Workers need to reject the current political rhetoric surrounding parenting which places responsibility for child outcomes with parents, whilst underplaying socio-economic factors. On a practice level, Social Workers can consider what constructs they being to an assessment and whether their work reinforces a static notion of parenting. Try and incorporate these questions into your reflective practice: Am I focussing solely on assessment and parental behaviour, or am I actively seeking to enhance parental capacity through improvements in the problems that beset the parent. I imagine this would be an interesting discussion in supervision. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|