|

There are some important consultations happening at the moment and BASW wants you to have a say.

Knowledge and Skills Statement for Achieving Permanence Consultation Paper The Department for Education is seeking views on the content of a knowledge and skills statement for child and family social workers involved in permanence planning. The consultation is focusing on what social workers need to know and be able to do in order to successfully undertake the assessment, analysis and permanence decision and progress permanence plans with ‘urgency and skill’; and a statement to inform the content of a continuous professional development programme. Please read the consultation and key questions and forward your comments to Nushra Mansuri, Professional Officer, BASW England [email protected] by Monday 5 September 2016 Future of Social Care Inspection Consultation Paper This consultation seeks your views on proposed changes across Ofsted’s inspections of children’s social care. It has four parts:

Please read the consultation and key questions and forward your comments to Sue Kent, Professional Officer, BASW England [email protected] Monday 5 September 2016 Reporting and acting on child abuse – consideration of mandatory reporting Consultation Paper The government is consulting on options for reform of the child protection system in England, specifically in relation to reporting and acting on child abuse and neglect. This includes consideration of the introduction of mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect or an alternative duty to act which focuses on taking appropriate action in relation to child abuse and neglect. Please read the consultation and key questions and forward your comments to Nushra Mansuri, Professional Officer, BASW England [email protected] by Friday 7 October 2016

0 Comments

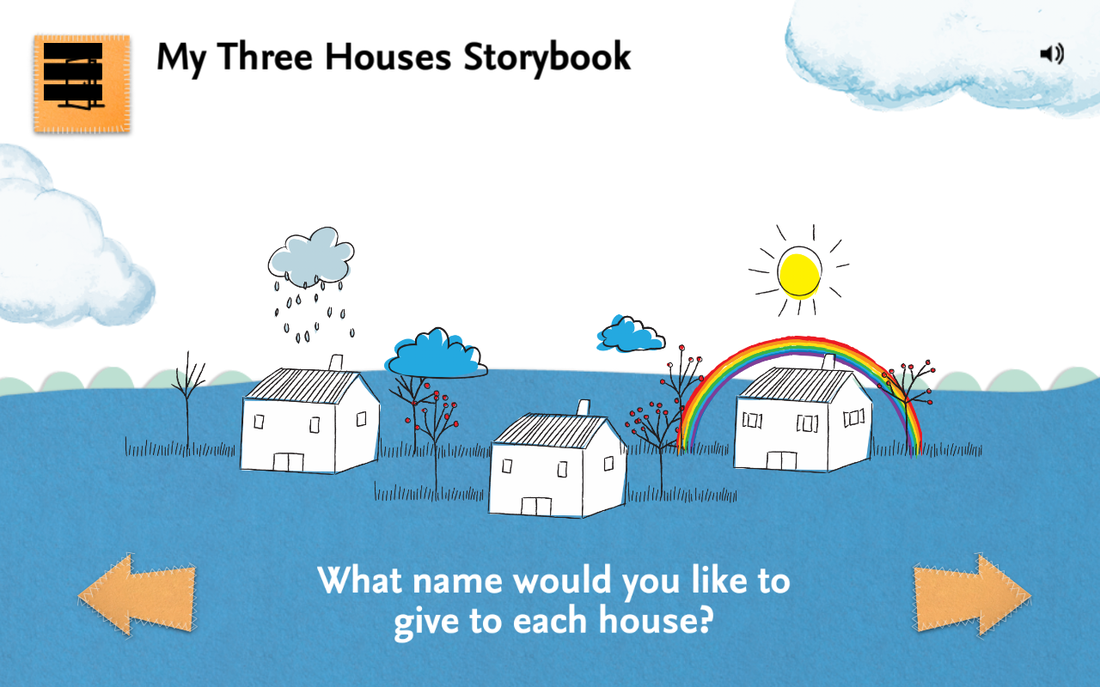

In 2010/11 Professor Eileen Munro reviewed the English children’s services system and found organizations and workers had become over-bureaucratized and compliance driven at the expense of direct work with families, parents and children. Following the recommendations of the Munro review, the UK government launched a Children’s Services Innovations programme which, amongst other things, has financed the development of a new app for social workers to use in their practice with children and families. Developed in Western Australia and designed with children’s services practitioners in UK, USA and Australia, the My Three Houses App offers a tool that taps into children’s love of all things iPad and encourages them to speak about what is happening in their life. The three houses tool was first conceived in New Zealand in 2003 and since then has been used by social workers all over the globe to place the voice of the child at the centre of child protection assessment and planning. I've blogged about using the analogue version here. This app brings the tool into the digital realm. There's video... Interactive animation... and a drawing pad for children.

The national social work evidence template (SWET) was launched in summer 2014 and all local authorities were encouraged to adopt it when submitting to court evidence to support and application for a care or supervision order. Its aim was to support local authority social workers in providing consistent and analytical court statements, in line with the Public Law Outline which requires succinct, clear social work analysis.

Following consultation, a review of the template and supporting documents was undertaken by the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) and the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (CAFCASS) which has resulted in the launch of a new updated social work evidence template. So, what’s changed?

Social Work Evidence Template (revised February 2016) Social Work Evidence Template – Final Evidence (revised February 2016) What a week it’s been for Social Work!

David Cameron announced a revolution in child rearing by suggesting that all parents should attend classes on how to discipline their children. A few years ago I would have welcomed such an investment; however, his continued focus on pathologizing parents whilst downplaying poverty and structural inequalities has left me exasperated. Nicky Morgan announced a ‘series of changes that will radically transform the children’s social care system’. These included a new regulatory body for social work to ‘drive up standards’ in education, training and practice, replacing the HCPC which succeeded the GSCC in the governments drive to cut costs by abolishing quangos only three years ago. And then there was the College of Social Work which was supposed to be the voice of our profession which lasted all of 2 minutes. An announcement to change laws so that councils and courts would favour adoption over other forms of care resulted in Ms. Morgan coming under fire for a foster care ‘slur’. And Frontline, a scheme to recruit ‘high-calibre’ graduates into the profession, piloted since 2013, announced its nationwide roll out. BASW have cautiously said that it is too early to tell whether this scheme will have the impact it hopes to achieve. I suspect that it will do very little. Existing workers need the support and resources to do the job they are qualified to do. I'm not saying that graduates have nothing to offer the Social Work profession – they do - but they're not superhero's that can be parachuted in to fix the problems of cash strapped authorities. I qualified as a Social Worker after first gaining an undergraduate degree in Sociology. I think this background gave me a strong grounding but not, I suspect, for the reasons the Government would like to see. Sociology is a discipline that is central to the understanding of structural inequalities and an appreciation for differences of epistemological views. However, these studies did not make me a better local authority Children’s Social Worker. They did not equipment with the life skills to work directly with different sections of our society. These skills were learned on the job. In my experience, those that do it best are the workers that have qualified later in life. Those that have ‘done the time’ in support roles and have been sponsored to do the undergraduate degree by their employer. These are the workers that have the passion to remain in frontline practice and hone their skills in direct work. But with local authority budget cuts, a lack of finance options for mature students and a fixation by this government to ostracise those already in social care, options for these dedicated and valuable colleagues are disappearing. I do not believe it’s the business of government to intervene in academia. The degree should equip practitioners with the knowledge, skills and desire to challenge oppression and inequalities. That syllabus should not be shaped by the very people Social Work should seek to challenge. By all means, support, train and nurture those in statutory agencies to do the job they are employed to do. Monitor and evaluate their competencies through a regulatory body. But government should not be undermining the professions foundation, the core values and the very essence of what it is to be a Social Worker. I subscribe to the international definition of Social Work. I started my first Social Work role 5 years before I qualified, working for an international NGO compiling research and assessments that were used to advocate for indigenous populations around the globe. Whilst you don’t need to be a Social Worker to do this role – it is Social Work. Family Support Workers are also doing social work. Academics that research and highlight oppression, structural inequalities and social exclusion are doing social work. However, if we get to the point where only those that are happy to police the poor are supported to succeed and retain the title, the profession is going to be in peril. But there is hope! BASW, the largest members-led association for social work in the UK, has its 2020 vision and there is a growing number of Social Workers that are speaking up publicly; airing their dismay at the governments continuous cycle of investigations and reviews with little action or meaningful investment (The cynic in my suspects they are waiting for a report to recommend scrapping the lot of us). I was moved reading Social Work Tutor’s open letter to the education secretary on Friday. However, Ermintrude said on Saturday that she was not longer sure whether she could continue to identify as a Social Worker following the latest announcements (Please don’t leave us!). We cannot allow the government to define us. We are a part of a diverse international community with an important history and, if we fight for it, a future of equal importance. Stay strong everyone! Your profession needs you!

The All Party Parliamentary Group on Runaway and Missing Children and Adults is inviting interested individuals and groups to submit written evidence to its current inquiry into how the police, children's services, schools and other professionals safeguard children who are categorised as 'absent' from home or care or education. The inquiry is intended to examine how the introduction of the ‘missing’ and ‘absent’ categories has affected the safeguarding response to children who run away.

Ann Coffey MP raised concerns about the new absent category in her report published in October 2014 ‘Real Voices – Child Sexual Exploitation Greater Manchester’. The deadline for submissions of written evidence is Friday, 22 January 2016. You can find out more information here. Further reading: Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care. Report from the Joint Inquiry into children who go missing from care (June 2012). Today Ofsted published it's annual report on foster care provision in England.

The statistics (April 2014 to March 2015) take a broad look at fostering provision across the country. They include data on children, their characteristics, experiences and safeguarding; capacity, including types of places and occupancy rates; foster carers, including ethnicity and training; recruitment and retention of foster carers; as well as complaints and allegations of misconduct. The data allow for comparison between local authority and independent fostering services as well as by region. The inspectorate received responses from 152 local authority fostering services and 293 independent fostering agencies (IFAs). Key findings include:

For the first time, Ofsted also asked services for data on child sexual exploitation (CSE) and children in foster care. 3% of children and young people were reported as being at risk of CSE during the year (2,690), while 1% were reported to be subject to it (865). You can read the full report is here. On 24 November 2015 I attended The Family Justice Council's 9th Annual Debate at the Strand Palace Hotel in London. Twitter users were able to read key points by following the hashtag #FJC2015, as I and other attendees live tweeted key points/events of the night.

The topic for this year’s debate was adoption and the motion read: “Adoption without parental consent is wrong in principle” The event was chaired by the Rt. Hon. Sir James Munby, President of the Family Division of the High Court, and Chairman of the Family Justice Council. The speakers were:

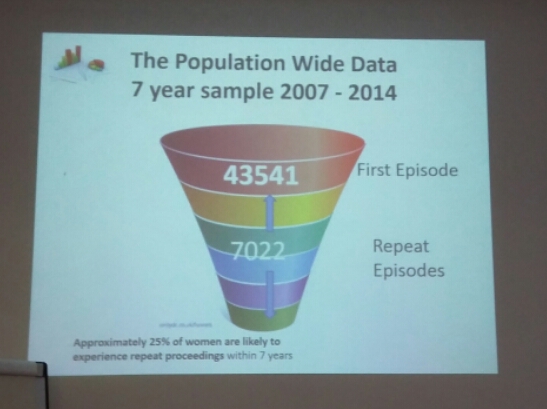

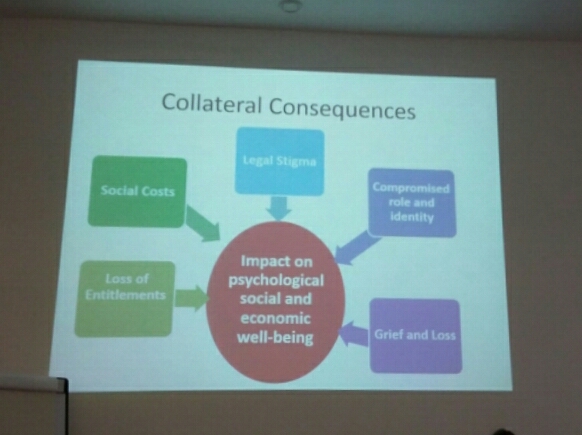

Transcripts and a podcast from the debate are now available on the Family Justice Council website. Yesterday I attended ‘Parents’ Voices and their Experiences of Services’ at Friends Meeting House in Manchester. It was an opportunity to examine priorities for system, policy and practice change, drawing upon findings from research and was a very valuable day for reflective practice. The event began with a short introduction by Safeguarding Survivor who chaired the conference with great confidence and professionalism. I know she was nervous but you couldn't tell and she did a brilliant job. If you aren't aware of her story, I recommend you read her blog. It offers great insight into the child protection system from a parents’ perspective and provides excellent advice for others whose children have been identified as ‘at risk’. Her work has been praised for its balance and value by Sir James Munby and you will soon be able to read more of her case after the court granted Louise Tickle (a freelance journalist) permission to publish details in a broadsheet newspaper. You can read the judgement at Family Law.  Siobhann and three mothers from The Mothers Apart project (Women Centre) Kirklees spoke about their book In Our Hearts. It presents open and honest accounts of initial separation, court proceedings, relationships with services, of mothers who have been able to have children returned to their care or contact increased, mothers who have no current contact at all and those for whom contact remains limited. It offers itself up as an aid and guide to learning for parents, families and professionals working in pursuit of child protection. As a result of co-production learning Mothers Apart have developed women centred working that recognises people as assets. Whilst every woman is different they have found that there are a number of common themes and, consequently, much of their work is about power. Sean Haresnape (Principal Social Work Advisor) from Family Rights Group outlined a Parents Charter being developed in collaboration with parents and professionals, that sets out expectations of how services should engage with parents, whose children are subject to statutory interventions; and we heard from Declan, a father and care leaver who had his daughter placed with him following care proceedings. Prof. Karen Broadhurst (Lancaster University) and Claire Mason (ISW & Lancaster University) presented preliminary findings from their 2 year study of birth mothers, their partners and children, within recurrent care proceedings under s.31 of the Children Act in England. The project hopes to confirm the national scale and pattern of recurrent proceedings together with the characteristics and service histories of parents caught up in this cycle. Statistical methods have been used to quantify recurrence and examine the relationship between recurrence and key explanatory variables. This has been complemented by qualitative components that include in-depth interview work with birth mothers in five local authority areas and in-depth profiling of a subset of randomly selected case files. Through data mining they have found that 25% of women who have been through care proceedings will return within 7 years. Teenage motherhood is associated with a significant number of repeat care proceedings and Prof. Broadhurst questions whether the family court is the most appropriate setting for dealing with teenage parents. Another facet of their research looks at the collateral consequences of care proceedings and asks who, once a court case has concluded, is there to support parents with the psychological, social and economic consequences of losing a child. Whilst the child and adopters/foster carers remain supported for a time by Social Workers and other services, there are no statutory support available to parents. This short-sighted approach demonstrates a lack of understanding of the collateral consequences and their cumulative impact which can drive women in to unhealthy relationships and successive pregnancies. In subsequent cases Local Authorities and Courts have been found to act more swiftly and are more likely to remove closer to birth, with adoption being the most likely outcome, compounding the cycle.

Similar concerns were raised last week by Sir James Munby when I attended the annual Family Justice Council debate in London. He said that it was “not fair on subsequent children that post adoption support isn't provided to birth parents” and “there is some substance to the question whether resources are adequately balanced between support for adoption and support for families”. Finally, Prof. Kate Morris (Sheffield University) outlined the empirical research she and Prof. Brid Featherstone (University of Huddersfield) are conducting as part of Your Family Your Voice – an alliance of families and practitioners working to transform the system. Their work, looking at family experiences of multiple service use, highlights the profound difficulty families often find navigating their way through services. At the end of the presentations we were asked to reflect upon what we had heard and identify what changes could be made to make the system a more humane one and minimise trauma for parents, children, their families – and also for practitioners. I invite you to do the same and participate in the research here. Today was the day George Osborne revealed his much anticipated, forewarned and feared Autumn Statement and Spending Review. Below I have summarised the key items I find particularly relevant to those working with children and families (I like lists and bullet points). I haven't added any analysis or comment yet but hope to put something together soon.

EDUCATION

*I’ll update this post as more details are revealed. As part of my research I have been looking at the construction of parenting and, specifically, mothering. How expectations of the parenting role has changed over time and how this has shaped and been shaped by government policy and legislation. I'm going to try and blog about pieces that I think will be particularly interesting to Social Workers, as I know quite a few of you follow my page, but I'll try not to bombard you too much with academic content.

Today I read The Social Work Assessment of Parenting: An Exploration by Johanna Woodcock. Although it was published in the British Journal of Social Work over a decade ago (2003) I believe her findings are still relevant today and would be a good read for any practitioner wanting to reflect upon their own construction of parenting and practice. Woodcock’s paper draws on a qualitative study of Social Workers conceptualisations of parenting and the relationship this construction has with practice. Within her exploratory study, Social Workers were asked to describe and give their opinions on the parenting that occurred within a case that they brought forward. Analysis of the data she obtained revealed four types of expectations that underlay judgements of parenting deemed both ‘good enough’ and ‘not good enough’. 1. The expectation to prevent harm. Woodcock found that Social Workers were influenced by legal or quasi legal constructions of parenting. Their overriding concern was the capacity of the parent to prevent harm and relied upon the presence or absence of evidence of ‘physical abuse’ ‘emotional abuse’, ‘sexual abuse’ or neglect in making this judgement. 2. The expectation to know and be able to meet appropriate developmental levels. Woodcock found that Social Workers attributed a parent’s failure to protect their child from harm to their limited understanding of their child’s stages of development. Woodcock highlighted the narrative from one case where a parent and social worker were unable to agree on the level of appropriate supervision. A second area of Social Worker concern manifested when a delay in growth and development was deemed to be the result of poor parenting. 3. The expectation to provide routinised and consistent physical care. Parents were expected to appreciate the importance of routines and demonstrate their capacity to carry them out Woodcock found that routines were a key element of Social Work discourse. ‘Not meeting the child’s needs’ invariably referred to a lack of routine and consistency and that the child’s emotional needs for a sense of safety and security were not being met. 4. The expectation to be emotionally available and sensitive. For some Social Workers it was insufficient for a parent to simply love a child. They needed to have more insight into the emotional reasons for a child’s behaviour, which took them beyond physical care and to demonstrate a level of affect and interest in the parent-child interaction. Woodcock also looked at the Social Workers’ ‘psychological appreciation’ of the parent. She found that one way in which social workers made sense of problem parenting involved whether the parent was psychologically ‘damaged’ or ‘disturbed’ through abuse, or a lack of consistency or emotional warmth in their own childhood. Alternatively, early experiences were seen to provide modelling for future parenting and the absence of a positive role model accounted for their lack of ‘knowledge'. Importantly, Woodcock noted that these explanations draw on two implicit competing theoretical orientations: psychoanalysis and social learning theory; and despite being assimilated into assessment this evidence base was not evident in intervention or treatment. Conversely, Social Workers relied on exhorting parents to change or ‘getting them’ to take responsibility. She found little evidence of attempts through intervention to address these deeply ingrained psychological needs, either through direct social work or referral to psychological services. When psychologists were called upon it was to contribute an opinion with regard to the parent’s capacity to change rather than to help facilitate that change. Woodcock asserted that it was this incoherence between the intervention strategy and the social workers construction of parenting which inevitably led to resistance. Somewhat ironically, it is also resistance and an ‘inability to work with agencies’ that compounds an assessment of poor parenting. The main concern for practitioners should be Woodcock’s identification of a ‘surface static’ notion of parenting. A surface response means that the psychological factors underlying parenting problems remain unresolved. By relying on exhortation to change, rather than responses informed by psychological observations, Social Workers create an environment that is unconducive to change and thus perceptions of parent ‘resistance’ more likely. An explanation offered by Woodcock for the presence of a ‘surface-static model’ is the fact Social Workers are increasingly directed to their legal responsibilities to ensure the protection of the child from harm, rather than on problems that beset the parent. This professional quandary has, in my opinion, only worsened in the intervening decade and is something that government needs to address if outcomes are to improve. Social Workers need to reject the current political rhetoric surrounding parenting which places responsibility for child outcomes with parents, whilst underplaying socio-economic factors. On a practice level, Social Workers can consider what constructs they being to an assessment and whether their work reinforces a static notion of parenting. Try and incorporate these questions into your reflective practice: Am I focussing solely on assessment and parental behaviour, or am I actively seeking to enhance parental capacity through improvements in the problems that beset the parent. I imagine this would be an interesting discussion in supervision.

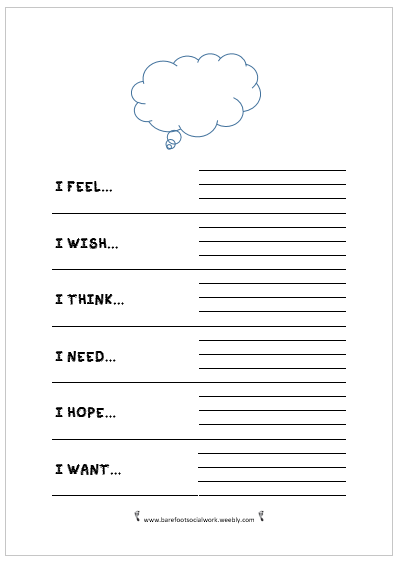

I've just added a new assessment exercise to the tools section of my website. It's pretty self explanatory. It can be self completed by a client, or during an assessment session, to establish what they want to change, achieve or work towards. It would compliment a motivational interviewing approach which you can check out in my previous post here. Let me know if you use it! :-)

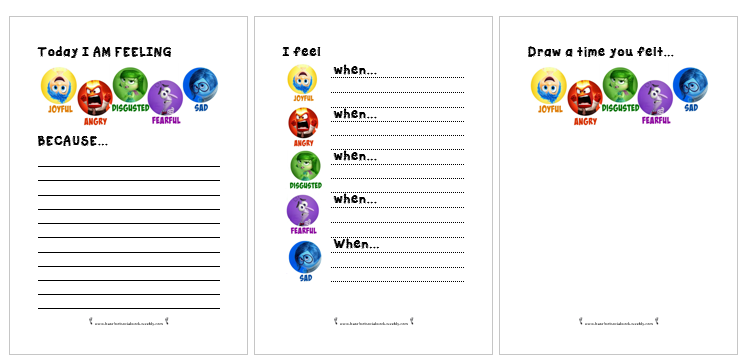

A year or so ago, I remember reading an article on The New Social Worker by Addison Cooper about ‘How Movies Can Help in Working with Kids’. If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do. It won’t take very long. Basically, she talks about how ‘movies can provide an excellent and easy way to connect with clients’ and ‘provide them with understandable analogies’. I think most Children’s Social Workers draw upon popular culture in their work. Cbeebies characters provide a universal conversation starter for most pre-schoolers and The X Factor is usually good with Teens. But we can also, as Addison points out, use them to help children understand their own emotions and circumstance. This summer’s movie Inside Out has received fantastic reviews and looks like a brilliant resource and tool for Social Workers. Take a look at the trailer if you haven’t already seen it. An article in The Guardian calls it a crash course in PhD Philosophy of self. It tells the story of 11 year old Riley, who moves to a new city and tries to make sense of her environment. The central characters Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust live in Headquarters, the control centre inside Rileys mind. Of course, in reality, there are more than just five emotions but that would have made the storyline a little too complicated. Whilst initially viewers may perceive most to be negative emotions, as the movie progresses we see how they work together and play an important role in keeping Riley safe. A message that Social Workers will understand and be able to relate to in their practice. During one scene Joy tells Sadness, drawing a small circle around the blue character, “your job is to make sure that all the sadness stays inside of it”. I find this quite profound as it is often what we see children encouraged to do when they are struggling with their emotions. Sadness and Anger can manifest in all sorts of ways that society perceives to be negative. Schools and classrooms aren't always set up to deal with the individual emotional needs of a pupil when their behaviour is seen to be impacting upon the learning of others around them. So, they are encouraged to ‘behave’, ‘be quiet’ and ‘calm down’. Hopefully Inside Out will help others to interpret children’s actions and foster empathy. It might also resonate with parents struggling to understand their child and how they can best support them. I’ve put together a couple of resources that you might like to use. Please feel free to download and share. Amazon also sell figures that could be incorporated into direct work or you can print off some of the colouring pages from the Disney website.

As some of you will already know, I am a Social Worker and Blogger here at Barefoot Social Work . I am particularly interested in adverse childhood experiences and finding ways in which children and their families can be supported to mitigate their negative long term affects. I am passionate about supporting children to remain in the care of their family and I believe strongly that local services should be available to make that happen. That is why I am particularly concerned (and have blogged) about austerity and the impact this will have on vulnerable children and their families. I believe Social Workers should help shape the political debate about issues that affect the people we support. We can do this in a number of ways: private conversations, engaging with media outlets, campaigning, petitioning and social research (to name a few).

Last week I was offered the very exciting opportunity to undertake a Phd at Manchester Metropolitan University. My study will look at 'Enabling Families in Austere Times' and will include a detailed ethonographic exploration of Home Start in England. The austerity narrative dominates the shaping of social care services and families’ experiences of care within Britain. Anxiety and insecurity are prevailing aspects of contemporary life and research highlights the negative impact on low and middle-income families. Government policy and the recent conservative budget increasingly emphasises the importance of ‘good’ parenting, with parents being expected to be responsible citizens, bear the impact of austerity measures, and take the blame for a myriad of societal issues. Third sector organisations play significant roles in the delivery of social care, particularly within a landscape of welfare state retrenchment and pressure on support services. However, there are significant gaps in empirically-based research that clarifies the distinctiveness of organisations. Home-Start has been the focus of limited research focused on enhanced children’s school readiness (Love et al., 1976) and improvements in children’s behaviour (Hermans et al., 2013). Existing research does not focus on the role that Home-Start performs in local communities, the diversity of families or the experiences of volunteers. In 2014 my research supervisor, Jenny Fisher and colleagues, undertook a small-scale evaluation of Home-Start Manchester South. This identified that they provide an invaluable support for families experiencing difficulties across South Manchester through the role of volunteers. The main aim of my research is to build upon the previous research and interrogate the impact of Home-Start on families in austere times. This will develop an empirically and theoretically sound understanding of family support and characteristics of Home-Start in supporting families. If you have followed the news around Kids Company over the last couple of weeks you will understand how important it is that organisations are accountable to those that invest personally and financially, and are able to evidence outcomes and efficacy. I am very excited about this opportunity and I am honoured that Manchester Metropolitan University and Home Start are supporting this research. I will start in September and would really appreciate your support. Please take a look at my fundraising page. If anyone is interested in following the progress of my research, I will be posting regular updates on my blog . Please follow me on twitter and facebook . Thank you x Family, What Family? Unpicking the tangled knot of human rights in child protection practice1/7/2015 Last night I attended a seminar hosted by BASW and the University of Wolverhampton. It was called 'Family, What Family? Unpicking the tangled knot of human rights in child protection practice' and delivered by Allan Norman. You might have heard of Allan before. He qualified as a social worker in 1990, and as a solicitor in 2000. He specialises in the law relating to the practice of social work, representing both social workers and service users through his own legal and independent social work practice Celtic Knot. He's also an Associate Lecturer at the University of Birmingham and now works as BASW’s lead on Policy, Ethics and Human Rights and International matters.

The seminar was fascinating and I came away with a greater clarity regarding the impact child protection processes have on both the rights of the child and family. Allan started by saying that Social Work as an international profession is fundamentally about human rights. The International Federation of Social Workers say just that in the Global Definition of Social Work. But for those working in areas of safeguarding that commitment to both positive and negative rights becomes complicated. We also find that absolute rights always trump qualified rights. So, a child's absolute right under article 3 ("No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment") trumps the parents qualified right under article 8 ("Right to respect for private and family life"). Allen questioned whether low level neglect was sufficient for article 3 to be engaged. No doubt the impact of austerity and the increasing threshold for support and preventative services will muddy these waters even more. Earlier today I read that all four UK Children’s Commissioners have called on the UK Government to stop making cuts to benefits and welfare reforms in order to protect children from the impact of its austerity measures. Tam Baillie, Commissioner for Children and Young People Scotland, said "For one of the richest countries in the world, this is a policy of choice and it is a disgrace. It is avoidable and unacceptable." It is right that children are safeguarded from significant harm, but removing them from their family is a hugely draconian step which should be reserved as an absolute last resort. How many families might still be together if the government prioritised funding for welfare, support and preventative services? In individual cases it may be that there are no other support options; but as a society do we not have a moral duty to make that support available? As a society are we failing in our duty to meet the positive rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? It's food for thought... Allan has written prolifically on the subject of Human Rights and child protection. If you're interested in reading more, take a look at some of these: ‘Working Together 2013 ignores human rights and we must act on this’ Disappearing act Dealing with the inconvenient human rights of others You might also like some of these (Not by Allan!): We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures I Have the Right to Be a Child Ethics and Values in Social Work (Practical Social Work Series) BASW Human Rights Policy (Sort of by Allan!)

The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred system was for Social Workers to have the time and skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. I posted about this in Direct Work with Children and Young People: Houses and Faces and described a couple of activities that I have found particularly useful in the past.

Direct work with Children and Young People demands time, skill and creativity. It’s about more than simply asking the child “how are things at home?” and whilst pen and paper may be sufficient for some children, others may need different media to make sense of their wishes and feelings. That’s why I find it particularly helpful to have a ‘Social Work Tool Kit’. It’s nothing fancy – many of the items can be kept in a small bag/box in your car and brought out as and when they're needed. Most Social Workers will already have an idea of what’s useful to them and the children they work with; but after receiving a couple of emails on the subject I wanted to post my recommendations. So, here they are… (*There are affiliate links embedded in all the pictures)

Thanks for reading! Please let me know what's in your Social Work Tool Kit by commenting below.

I’ve seen a couple of ‘Missing Child’ posts on Facebook this week and I wanted to explain why I won’t be sharing them. They are always heart wrenching pleas for help. Some of them, I have no doubt, are genuine. I know this as a quick search on Google and I find that the police are also concerned for their whereabouts and are actively searching for them with the support of authorised charities and agencies. However, there are some that are not what they seem*.

Some are simply a hoax and some of them are not ‘missing’ at all. The child may have been adopted due to the risk of significant harm; they may be in hiding with their other parent as a result of serious domestic violence within the home; or the whole family may be in police protection and the concerned ‘father’ is not who he claims to be. Furthermore, ‘missing adults’ may wish for their location to remain anonymous, and they do have that right which we must respect. As virtual strangers we do not know the circumstances of their ‘disappearance’ and we should trust in the expertise of professionals to get the full picture. In October 2013, there was a case in Sweden where a father published a photo of his missing children and asked for help in finding them. Thousands of people helped by sharing the post and finally one person recognised the children and let him know where to find them. What Facebook users weren't aware of was that the mother and her children were living under protection and with a new identity after leaving the father. When he found them they were forced to move again, but the consequences could have been much worse. Jayne has also been in touch to say that she "know[s] of a Father who'd been rehomed with his children and the Mother found her children who were in protective custody from her using facebook. Really good to make people aware!!". In other cases here in the UK, the birth parents of adopted children are using Facebook and other social networking sites to track down their children, flouting the usual controls and safeguards. Incidents are becoming more and more common and many local authorities are now advising adoptive parents not to include photographs in their annual letters, in case these are posted online in an attempt to trace the child. F.m has said: "We have 3 children who are adopted, and we had this happen. We had sent the birth family photos with the letter of our girls as bridesmaids. They were then posted on Facebook as 'abducted, please help us find them', very scary indeed. They were removed from their birth family for very good reason, and must be protected from them for life. Social media is dangerous and we live in fear of someone posting something which helps birth family find them." So, what can you do to help?

Thank you for all the likes and shares on this post. Please take a look at the rest of my blog. You can also follow me on facebook and twitter. * This post is not referring to genuine appeals for information by the police or any authorised charity acting on their behalf.

Childhood is a time of rapid change. Some of these changes are obvious, such as height gain, language ability and physical dexterity. Others are less obvious, such as how children make sense of the information in their environment. To understand the rapid changes of childhood, children’s abilities are often judged against developmental milestones, such as acquiring language (babbling, talking), cognition (thinking, reasoning, problem solving), motor coordination (crawling, walking) and social skills (identity, friendships, attachments). But how does digital technology influence the acquisition of these important skills? Does technology hinder a child’s physical, social and cognitive development, or does it provide exciting opportunities for learning?

The entertainment and interactivity of tablets and smartphones has made them attractive to children. Touch-screen interfaces mean that digital technologies are now accessible for children at a very young age. But do children find digital technologies exciting for reasons beyond simple entertainment? The amount of digital technology available to my young daughters is massively different to that in my own childhood. As both a parent and a Social Worker, I've found it difficult to make sense of media reports and research findings in this controversial area. Is technology beneficial or detrimental to child development? Does screen time lead to increased distractibility, obesity and loneliness? Or does it offer opportunities for autonomy and experimentation beyond anything imagined when I was a young child? As the generation gap widens between adults and children’s' understanding of new technologies, how will we protect them from the risks while allowing them to benefit from the opportunities new technologies offer? In 2014 both Ofcom and the NSPCC (Jütte et al.) found that one in three children owned their own tablet. Figures published by the NSPCC also show smartphone ownership increasing with age (20 per cent of 8–11-year-olds and 65 per cent of 12–15-year-olds). These profound changes are reshaping children’s digital environment. The recent EU Kids Online Network project, called Zero to Eight, illustrates just how pervasive technology is becoming for younger children. The project report identified a significant increase over the previous five years of children under nine years old using the internet (Holloway et al., 2013). In particular it noted a growing trend for very young children (pre-schoolers) to use tablets and smartphones to access the internet:

Whilst children are now going online at a younger age, their ‘lack of technical, critical and social skills may pose [a greater] risk’ (Livingstone et al., 2011). The challenge for parents is how best to manage the risks alongside the benefits. I’ll get back to this later…

Children and Digital Technologies Children are often very engaged by digital technology. But why is it so compelling for young children to spend so much time interacting with their digital world? Firstly, technology is fun. Child-centred technology in particular is especially designed to be as entertaining and captivating as possible. Similarly, a big attraction of technology for children is that they see their parents and peers using it, and a major part of childhood is ‘modelling’ the behaviour of those around them, particularly parents: that is, children learn from observing and imitating others around them. Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory (SDT) seems particularly relevant to untangling the reasons behind young children’s fascination with the digital world. According to SDT, there are two overarching types of motivation, ‘intrinsic motivation’ and ‘extrinsic motivation’. The former refers to doing an activity for its own sake because it is enjoyable and this is thought to lead to persistence, good performance and overall satisfaction in carrying out activities. Ryan and Deci outline three basic psychological needs associated with intrinsic motivation that can be applied to children’s use of technology:

Although each of these three basic psychological needs may not be met for every child, the self-determination theory offers a good psychological basis for understanding children’s intrinsic motivation in using technology. According to one study, children are currently spending more time with technology than they do in school or with their families. Similarly, children as young as 2, 3 and 4 are playing with their parents’ phones or tablet devices; and some psychologists argue that this has an enormous impact on their brain development, as well as on their social, emotional and cognitive skills. This raises an important question: in this 24/7 digital world, should parents be setting new rules for their children’s engagement with technology? Should we be promoting new parenting classes for the modern age? Generational Divide The idea of a generational divide between children and adults has been a popular topic among psychologists and sociologists. This has resulted in the use of labels such as the ‘digital native’, the ‘net generation’, the ‘Google generation’ or the ‘millenials’, each of which highlights the importance of new technologies in defining the lives of young people. The most contentious term is the ‘digital native’. The term first appeared in an article by Marc Prensky to describe those children who spend much of their lives ‘online’, constantly ‘switched on’. It represents ‘native speakers’ who are ‘fluent in the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet’. There is a distinction between ‘digital natives’, who are those generally born after the 1980s and are technologically adept and comfortable in a world of technology, and ‘digital immigrants’, who are generally born before the 1980s and are fearful or less confident in using technology. To justify his claims Prensky draws on the widely held theory of neuroplasticity. This means that our brains are highly flexible and subject to change throughout life. The different neural connections in the brain change and evolve throughout childhood in response to the environment. It is claimed that young children’s brains now are developing differently to the way adults’ brains have developed, as children are growing up surrounded by new technologies. This topic of neuroplasticity is something that I have also covered in Risk, Resilience and Adoption. Safeguarding Many parents, teachers and Social Workers have legitimate reasons to worry about children’s engagement with the digital world. We know that children are likely to run risks if they access the internet unsupervised, or stay online for long periods of unbroken time. Examples of the apparent risks appear in the work of Howard-Jones, who analysed current research in neuroscience and psychology. He states that the developing brain can be susceptible to environmental influence, and digital technology opens it to risks including:

You can also find research into internet addiction, aggressive game-playing, grooming and bullying, which have also been linked to children’s exposure to the digital world. Social Media can also present problematic situations for adopted children, and those in foster placements or subject to child protection plans. Even the Pope waded in on the debate earlier this month, warning parents not to let children use computers in their bedrooms because of the 'dirty content' on the internet. Whether you are a digital optimist or pessimist, it’s obvious that while technology brings about opportunities, it also has associated risks. This has led to some professionals arguing that parents should limit young children’s use of, and exposure to, new digital technologies. But is this really the answer? Is simply restricting children’s access actually the best way to ensure their safety? Restricting access to technology may also restrict opportunities for children to develop resilience against future harm and I would argue that simply restricting access or removing technology from children’s lives seems inappropriate (except as a short term measure in cases where technology is presenting a significant risk of harm to the child). Perhaps we need to review parenting methods so we ensure sufficient levels of support for children growing up in this highly digital modern world. If we look at self-determination theory, the idea of giving children autonomy and choice to make appropriate decisions about their own digital world could be the answer. According to some, we need to trust in the maturity and judgement of children. We have to be able to trust their social skills in successfully negotiating these new ways of behaving and successfully managing or avoiding risks (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). It is important to recognise that children’s perceptions of problematic online situations may differ greatly from those of adults. Because of the different perceptions of adults and young people, and the lack of a neat distinction between positive and negative experiences online, many professionals opt to avoid the term ‘risk’, and prefer to talk about ‘problematic situations’. Research by Vandoninck and colleagues, based within the UK, tackles the idea of giving children autonomy to make their own choices. Awareness of online risks motivates children to concentrate on how to avoid problematic situations online, or prevent them from (re)occurring. This brings me to the concept of preventive measures – what children actually do or consider doing in order to avoid unpleasant or problematic situations online. Vandoninck and colleagues identified five main categories of measures discussed in the literature:

Perhaps the key focus of parents and professionals should be on helping children to acquire the knowledge and skills to moderate their own online behaviours; to develop resilience to risks and to become responsible digital citizens of the twenty-first century (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). For more information about safeguarding, take a look at my other posts on online safety and follow me on facebook and twitter. Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence. Today Edward Timpson, Children and Families Minister, addressed the NSPCC conference about how social work reform and innovation can help better protect vulnerable children. He became a Member of Parliament in 2008 after winning a by-election in the constituency of Crewe and Nantwich. In September 2012, he was appointed as a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Education, and following the 2015 general election, he was promoted to Minister of State for Children and Families.

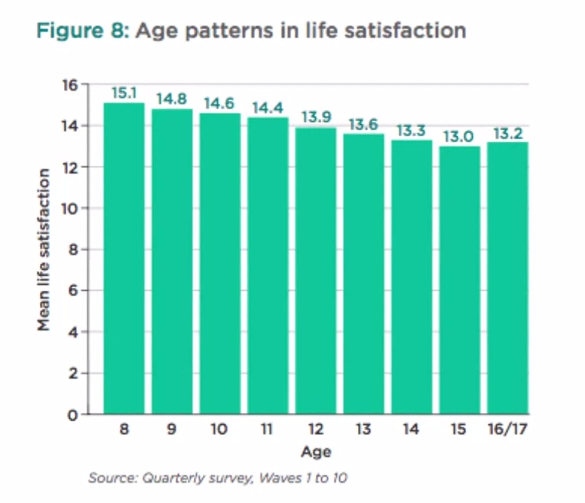

You can see the whole speech here, but I've summarised/quoted the main points below. He started his speech with a little self-deprecation, saying how thrilled and surprised he was to be back in office, before drawing attention to his own upbringing, in a household with adopted and fostered siblings, and his work with children in care. He says he believes “the protection of vulnerable children… [is] the most profound responsibility we have as a society". He said that during the last parliament he had worked to “strengthen the child protection system… with major reforms to social worker recruitment and assessment”. Also “the first independent children’s trust in Doncaster”, he claimed, are “freeing up local authorities so that they can set up new models of delivery”. Child sexual abuse and NSPCC report Referring to investigations in Rotherham, Rochdale and Oxford he said: “we’ve been able to shine a light on a police and social care system set up to protect children, but that all too often turned them away, leaving them in the hands of callous abusers”. He also said that “the Prime Minister has appointed Karen Bradley as a minister in the Home Office to tackle [CSE] alongside [him] - recognition that child sexual abuse is about child protection... but also about prosecution too”. Centre of Expertise Timpson reported that a “new Centre of Expertise” will try “to understand what works when it comes to tackling and preventing child sexual abuse”. In addition, he acknowledged “that while CSE is dominating the media, we must not lose sight of neglect”. That’s why, he said, they’re “looking at having a campaign to encourage the public to report all forms of child abuse and neglect”. Social work reform “At the heart of good child protection is, of course, good social workers”. He said that “the introduction of a new assessment and accreditation system for children’s social workers” will offer “a rigorous means of assuring the public that social workers…have the knowledge and skills needed to do the job”. His department will also continue to support “projects to bring the brightest and best into social work through Step Up to Social Work and Frontline”. Innovation programme Timpson said that he was “especially keen to see much closer working between the voluntary sector and local authorities - something the Children’s Social Care Innovation programme is encouraging and seeing take root.” There’s a “£1.2 million initiative with SCIE - The Social Care Institute for Excellence - that aims to help us learn better from serious case reviews (SCRs) and improve their quality, and which includes a pilot to improve how SCRs are commissioned”. There’s also a “£1 million funding for the NSPCC to introduce the New Orleans intervention model in south London - which aims to improve services for children under 5 who are in foster care because of maltreatment by promoting joint commissioning across children’s social work and CAMHS teams.” Character and resilience Timpson’s “brief has been extended to include character and resilience”, placing “a greater emphasis on helping children… develop the qualities and life skills that will give them a strong foundation for social life”. He told the audience of social care professionals that “there’s a need to get better and smarter about how we equip our sons and daughters with the attributes they need to find their feet today and truly flourish.” He concluded his speech by asserting that he is a “pragmatist and simply [wants] to do what’s best by and for children, wherever they are and whatever their circumstances.” Adolescence is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood and is a crucial developmental stage for our mental well-being. It is a period of physical, cognitive, social and emotional changes and it is important that adults supporting young people have a good grasp of the challenges they face. Physical changes in adolescence In 2013 The Good Childhood Report (The Childrens Society) charted the life satisfaction of a group of 8 to 17 year olds. They found that during this period life satisfaction declines. When it’s broken down the biggest drop seems to come from anxieties associated with physical appearance. Perhaps this isn't surprising considering that during puberty bodies’ change both in size and shape. Researchers have been debating a lot about whether and to what extent this may impact upon the body image and self-esteem of young people. While physical changes can be awkward for anyone, research suggests that adolescents who perceive their physical development as particularly early or late compared to their peers find it particularly difficult to adjust.

Brain development in adolescence While physical development can be quite obvious many parents and professionals are less aware that adolescence marks a period of profound cognitive development; a period of massive brain growth not seen since infancy. Recently research has been considering whether this can account for some of the common behaviours we see in teenagers: impulsivity, risk taking behaviours and intense emotions. Research has shown that it may have something to do with the pre-frontal cortex. In adults it is the part of the brain that helps us to maintain goal-directed behaviour, moderate intense emotional experiences and check our risky impulsive behaviour. Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence to indicate that purposive action selection depends critically on this particular region of the brain; however, it is also one of the last to develop. It is possible, therefore, that the risky and moody behaviour typically characteristic of this age group could have something to do with the late development of the pre-frontal cortex. Interpersonal relationships in adolescence Interpersonal development is a key stage in adolescence. It is a period of identify formation when young people become more oriented towards their peers, they individuate and separate, and become more autonomous from their family. Identity development correlates significantly with the quality of peer relationships, with their primary caregivers, and with any younger people who are around them. Interpersonal development is crucial in adolescence, and a lot of the psychological resilience and vulnerability manifest here. Transition points between primary and secondary school, residential moves or any other circumstance that forces the adolescent to re-establish themselves within a new peer group are absolutely key. A lot of their personal identity development is who they are to others, and often the most important people to a young person are their peers and who they are to other young people around them. We can also see a high level of compartmentalization in adolescent social circles. That is to say, adolescents can often be somebody completely different to their families, to who they are to friends, to who they are at extra-curricular activities. That is one of the reasons why the quality of a young persons relationships and their social environment is so important and why experiences, such as bullying or social isolation, can have such a profound impact on a young person's mental health and well-being. One of the things that comes with emerging independence, and with individuating as a young person, is the formation of different bonds and different types of relationships. Indeed, the emergence of romantic relationships, and active and romantic feelings, are crucial. This is why it is important that young people have positive and healthy experiences. They are very vulnerable to exploitation and negative experiences which, again, can have a profound effect on their mental health and well-being. Young people tend to experiment a lot with intimate relationships, with romantic relationships, and different types of peer relationships. Sometimes it can be difficult for young people, when identities aren't fully formed and they are less clear about who they are to others, to know how to define these – are they a boyfriend/girlfriend, friend, sporting team mate? These difficulties and uncertainties can make them increasingly vulnerable in relationships where there is a disparity of power. Traditionally adolescence has been discussed and defined as a period of storm and stress. We expect high levels of conflict experimentation; a lot of adolescent identity development is in opposition to what is expected of them. Adolescents can be inter-personally challenging and difficult both within their families, within institutions, and any other contexts that they may find themselves in. They usually struggle with ideas of identity, conformity, and indifference. It is intensely difficult for young people to appreciate how they're perceived by others yet, at the same time, it's also very important to them. Adolescent development waxes and wanes, they can go from moratorium and uncertainty to premature identity formations. It is, therefore, important for parents, carers and professionals to consider these dynamic stages, as premature pinning of expectations can be quite detrimental. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|