|

Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence.

0 Comments

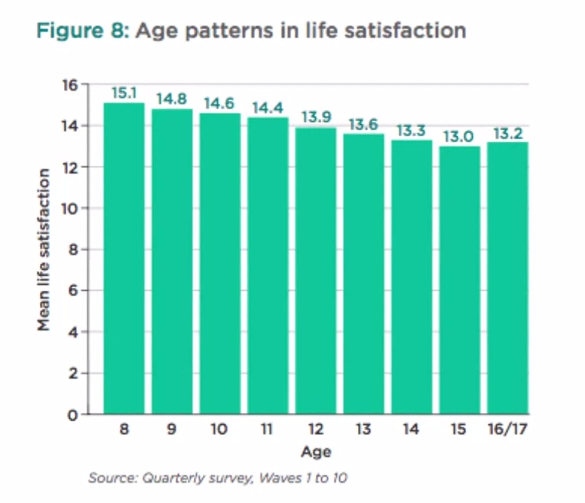

Adolescence is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood and is a crucial developmental stage for our mental well-being. It is a period of physical, cognitive, social and emotional changes and it is important that adults supporting young people have a good grasp of the challenges they face. Physical changes in adolescence In 2013 The Good Childhood Report (The Childrens Society) charted the life satisfaction of a group of 8 to 17 year olds. They found that during this period life satisfaction declines. When it’s broken down the biggest drop seems to come from anxieties associated with physical appearance. Perhaps this isn't surprising considering that during puberty bodies’ change both in size and shape. Researchers have been debating a lot about whether and to what extent this may impact upon the body image and self-esteem of young people. While physical changes can be awkward for anyone, research suggests that adolescents who perceive their physical development as particularly early or late compared to their peers find it particularly difficult to adjust.

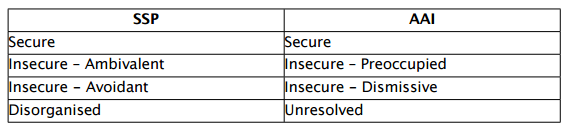

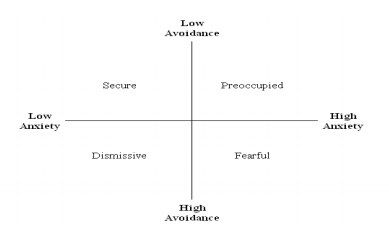

Brain development in adolescence While physical development can be quite obvious many parents and professionals are less aware that adolescence marks a period of profound cognitive development; a period of massive brain growth not seen since infancy. Recently research has been considering whether this can account for some of the common behaviours we see in teenagers: impulsivity, risk taking behaviours and intense emotions. Research has shown that it may have something to do with the pre-frontal cortex. In adults it is the part of the brain that helps us to maintain goal-directed behaviour, moderate intense emotional experiences and check our risky impulsive behaviour. Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence to indicate that purposive action selection depends critically on this particular region of the brain; however, it is also one of the last to develop. It is possible, therefore, that the risky and moody behaviour typically characteristic of this age group could have something to do with the late development of the pre-frontal cortex. Interpersonal relationships in adolescence Interpersonal development is a key stage in adolescence. It is a period of identify formation when young people become more oriented towards their peers, they individuate and separate, and become more autonomous from their family. Identity development correlates significantly with the quality of peer relationships, with their primary caregivers, and with any younger people who are around them. Interpersonal development is crucial in adolescence, and a lot of the psychological resilience and vulnerability manifest here. Transition points between primary and secondary school, residential moves or any other circumstance that forces the adolescent to re-establish themselves within a new peer group are absolutely key. A lot of their personal identity development is who they are to others, and often the most important people to a young person are their peers and who they are to other young people around them. We can also see a high level of compartmentalization in adolescent social circles. That is to say, adolescents can often be somebody completely different to their families, to who they are to friends, to who they are at extra-curricular activities. That is one of the reasons why the quality of a young persons relationships and their social environment is so important and why experiences, such as bullying or social isolation, can have such a profound impact on a young person's mental health and well-being. One of the things that comes with emerging independence, and with individuating as a young person, is the formation of different bonds and different types of relationships. Indeed, the emergence of romantic relationships, and active and romantic feelings, are crucial. This is why it is important that young people have positive and healthy experiences. They are very vulnerable to exploitation and negative experiences which, again, can have a profound effect on their mental health and well-being. Young people tend to experiment a lot with intimate relationships, with romantic relationships, and different types of peer relationships. Sometimes it can be difficult for young people, when identities aren't fully formed and they are less clear about who they are to others, to know how to define these – are they a boyfriend/girlfriend, friend, sporting team mate? These difficulties and uncertainties can make them increasingly vulnerable in relationships where there is a disparity of power. Traditionally adolescence has been discussed and defined as a period of storm and stress. We expect high levels of conflict experimentation; a lot of adolescent identity development is in opposition to what is expected of them. Adolescents can be inter-personally challenging and difficult both within their families, within institutions, and any other contexts that they may find themselves in. They usually struggle with ideas of identity, conformity, and indifference. It is intensely difficult for young people to appreciate how they're perceived by others yet, at the same time, it's also very important to them. Adolescent development waxes and wanes, they can go from moratorium and uncertainty to premature identity formations. It is, therefore, important for parents, carers and professionals to consider these dynamic stages, as premature pinning of expectations can be quite detrimental. Yesterday I posted about the origins of attachment theory. Draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argue that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. My personal experience of the Social Work Masters was that attachment was covered but in a rather one dimensional manner without the necessary critical analysis. In recent years, some assumptions have been challenged and this post will look at three of the main debates in the theories of attachment. These debates are ongoing and you will have to judge for yourselves. Adult attachment styles are dictated by the mother-child relationship. This assumption rests on the principle of monotropy, but recent reconceptualisations of attachment suggest that attachment might be more significantly influenced by multiple caregivers and relationships. There are three possible models: Firstly, the Hierarchical model is the classic understanding of attachment theory, in which attachment is to a primary caregiver (the mother) and that this relationship is concordant with other attachment relationships, and mediates future relationships. This model derives from Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s research. Secondly, the Integrative model describes an alternative organisational structure in which the child integrates all of his/her attachment relationships into a single representation. In this model, by Van IJzendoorn et al. (1992) they suggest that all attachment relationships are equal and independent, and the quality of the combined relationships best predicts his/her developmental consequences. The entire extended network of attachments is a better predictor of attachment than family attachment style only. Thirdly, the Independent model states that each attachment relationship brings an independent representation with qualitative differences, domain and person specific. For example, the child’s relationship with peers is more likely to be determined by the maternal attachment, whilst social competence, efficacy and adjustment is more likely to be determined by paternal attachment. The evidence for this model is less well-established, but Crittenden’s Dynamic Maturational Model uses a version of this as its basis (more on that later). There is evidence, both for and against these models using cross-cultural studies, studies of attachment in adolescence, and inter-generational studies. It's probably too much to cover right now but I may cover it in another post at a later date. A categorical classification system is the most accurate way to describe attachment styles. The two most significant attachment measures are the Strange Situation Protocol, used with toddlers, and the Adult Attachment Interview. Both allocate individuals to one of four categories. If you’re interested in finding out more about your own attachment style you might like to look at this online version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale, a test of attachment style. The ECR was created in 1998 by Kelly Brennan, Catherine Clark and Philip Shaver. It groups people into four different categories on the basis of scores along two scales. The inventory consists of thirty six that must be rated on how characteristic they are of you. If you do complete the above questionnaire, you will be given a classification made on the basis of a dimensional conceptualisation of attachment, that looks like the one below. Fraley & Spieker (2003) have argued that this provides a more sensitive and ecologically valid assessment of individual attachment style. Finally, Patricia Crittenden has elaborated further by creating a model of attachment called the Dynamic Maturational Model. Crittenden’s model assumes multiple frames of reference and context-dependent responses, centred around a cluster of sub-categories. So, instead of the individual being categorised, the individual has a set of strategies, which can be matched to a range on this sphere. She adheres very strongly to an evolutionary framework. To see an overview of her theory, take a look at this YouTube video where she gives a presentation, titled "The development of protective attachment strategies across the lifespan", at the BPS DCP Annual Conference in 2012: Attachment style is set by 12-18 months

Bowlby’s original theory implied, partly by its focus on a single caregiver, that attachment style might be set quite early on, although he explicitly allowed for life events and circumstances to allow change. However, it was Ainsworth’s development of the Strange Situation Protocol that really reinforced the idea that attachment style is set by the time of primary individuation at or around 18 months. There is evidence to support this stability of attachment style, but it is not black and white. Different studies have found that:

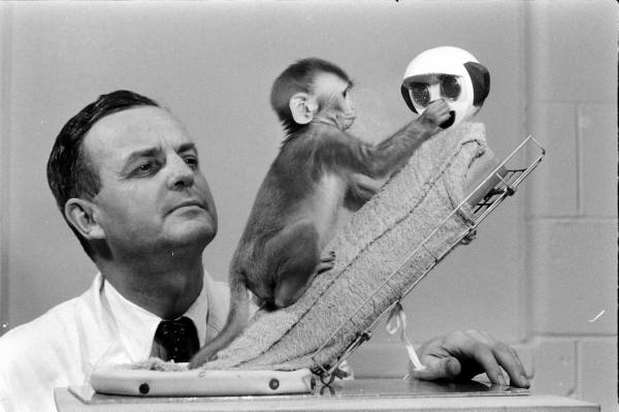

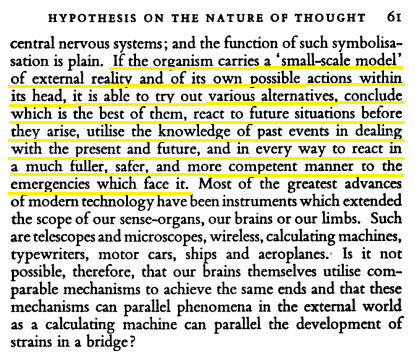

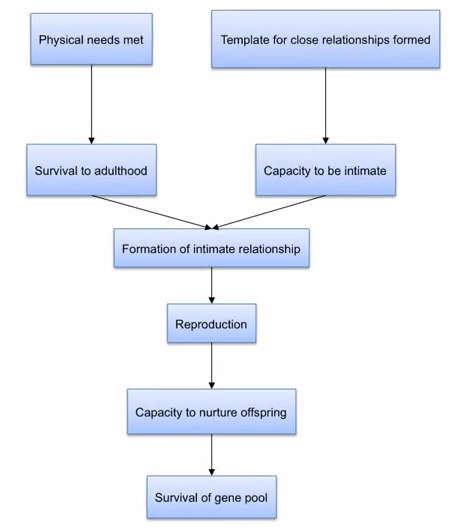

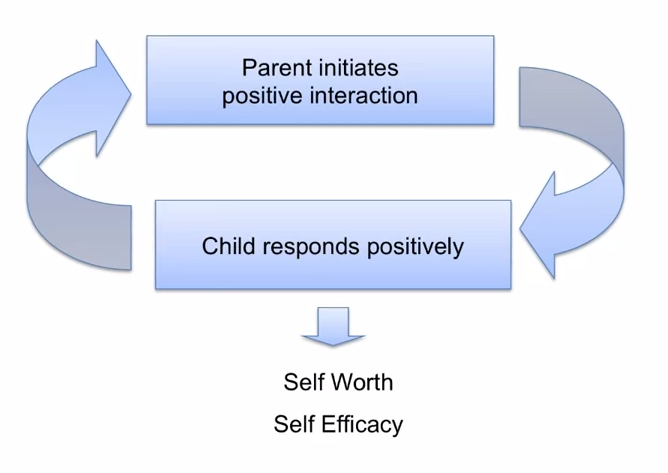

So, attachment classification certainly has predictive power, but not 100%. In adoption studies (See my previous post on Risk, Resilience and Adoption), children adopted before 12 months of age are only slightly more likely to be insecurely attached than children raised in birth families, whilst children adopted after 12 months are at significantly higher risk of insecure attachment, and disorganised attachment specifically. There are many, many more debates around theories of attachment. Too many to cover in a short blog post. However, I hope this has given you a tiny introduction to current thinking around the topic. It is important that practitioners are aware of these issues so that they can assess for themselves how best to integrate them into practice. Unfortunately, I can't give you a definitive answer about which theory or approach is best. You'll need to make an educated judgement based upon your own knowledge, research and professional experience. All social workers in the care system should be trained in recognising and assessing attachment, according to proposed guidelines. The draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argues that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. I couldn't agree more and I'm a little disappointed that this isn't already the case. This post, covering the origins of attachment theory, will be the first in a short series on attachment and it's implications for social work practice. Attachment theory is almost 75 years old. During this time, some elements have changed but the underlying principles remain as true now as then. In the 1940s and 50s John Bowlby worked with children who had been either separated from their parents as war orphans or evacuees or who had experienced significant adversity in their early life. He believed that these children went on to experience a range of emotional, behavioural and psychological difficulties as a result of their early experiences of loss and trauma. Bowlby has been criticised for developing a normative theory of development based on non-normative experiences. He was trained in a psychoanalytic tradition, but was disillusioned by its intrapersonal focus; instead he was influenced by the important empirical discoveries happening around the same time. I’ll outline some of them below: In his 1943 book, The Nature of Explanation, Kenneth Craik described the central nervous system as “a calculating machine capable of modelling or paralleling external events” and saw this as a basic feature of thought. He described the human or animal in this way: This might seem obvious to us now but to John Bowlby it provided a pragmatic explanation to the adverse developmental outcomes he had seen in orphans and institutionalised children; more so than the psychoanalytic training of his background because Craik’s theory was outward looking; seeing the individual in context. John Piaget described intellectual development as a process of adjustment and adaptation to the world. As part of this growth children have to go through a process of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation involves the inclusion of new information into existing schema or internal working models. Accommodation happens when a child is not able to assimilate information into an existing schema and either has to change the schema or develop a new one. Craik and Piaget were important for attachment theory because they explained how infants develop schemas or maps for future relationships based on prior experiences and learning.  Niko Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz were ethologists studying the sociology of birds. Their careers travelled in parallel, influencing each other along the way. Lorenz was inspired to conduct a study involving goslings which ultimately led to the imprinting hypothesis. In this study Lorenz split a large hatch of goslings, leaving half with the mother and taking the other half and raising them himself. Over the course of their development the goslings quickly identified him as their primary attachment figure and followed him, copying his behaviour. He taught them to swim, he used to call them with a special horn for feeding time and they always followed him. When they were given the opportunity to return to their birth mother, they didn’t recognise her as such, instead preferring Lorenz. This taught us about the importance and probable biological nature of the bond between mother* and offspring, in which the mother, the primary attachment figure, is the one who provides physical and emotional care and nurture. As a light break, you might enjoy the following Tom & Jerry cartoon where they, in a very flippant and simplified manner, explain the concept of imprinting. Later, in the 1960s Harry Harlow carried out a series of lab based experiments on monkeys (seen at the top of this post), rearing them in total social isolation. The study, which was unquestionably cruel, showed that monkeys were preferentially seeking out a cloth mother for nurturing; spending up to 18 hours a day holding onto her and seeking out a wire mother only for food. All the means for a healthy development were available and yet the monkey showed severe damage as a result of their experiences. The study suggested that mammals need reciprocal nurturing and attachment as much as they need their physical needs met. Bowlby hypothesised that since humans cannot survive without adult care our evolutionary history has selected pre-wired dispositions on both the part of the adult and the child that ensure human survival. From this basis, Bowlby developed a model of attachment that is monotropic (has a single attachment figure). It’s focussed on survival of the individual and the species and is integrated with human development to both influence broader developmental outcomes and be influenced by individual and contextual factors. Within this model tasks are identified for care giver and child that promote reciprocity and ultimately autonomy. The goal is to maintain emotional and physical equilibrium of the child thus keeping their attachment systems settled, allowing exploration and learning. During periods of distress the attachment system is activated and takes priority over the exploratory system. The regulation of emotion and behaviour are tasks that the care giver and child accomplish together through reliable, responsive and consistent care giving. The care giver provides the infant with the necessary up-regulation and down-regulation that the infant needs. Consequently, parents that are not attuned to the infants needs, and cannot reliably and consistently provide care, leave the child without the necessary external regulatory support. Over time this develops into a complex system which affects the way in which a child, and eventually adult, responds to their own needs and to those other others.

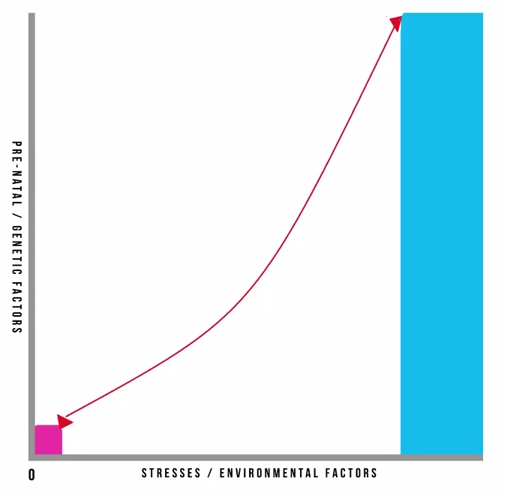

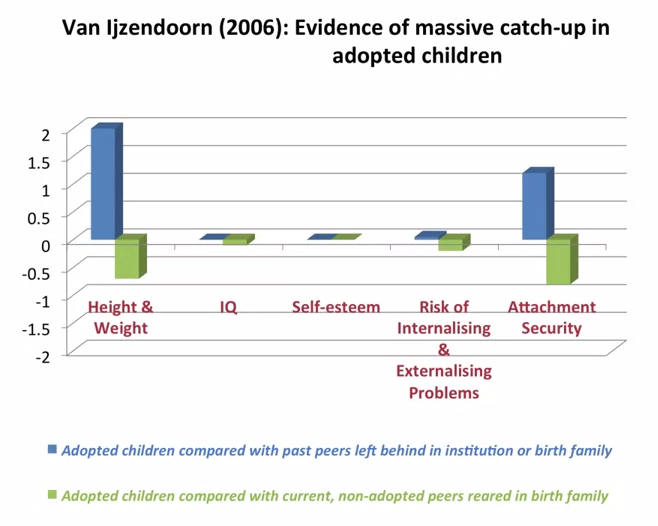

I hope you've found this post interesting. You might also be interested in my post on Attachment Based Family Therapy. I'll write more on the current debates in attachment and methods of assessment soon. Follow me on facebook and twitter so you don't miss them. Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

Last week I started a 6 week course with the University of Edinburgh called The Clinical Psychology of Children and Young People. Child psychology is an area that particularly interests me and I'll post some of my own interpretations of how the material can be used in social work practice. I have studied it extensively in the past; however, I believe that as Social Workers we should continually refresh and build upon the knowledge that forms a basis for our practice. Like renewing a first aid certificate. I hope you find these posts interesting and helpful. This week we looked a child and adolescent development, factors that influence development, and models of developmental psychopathology. An understanding of children’s development helps us to interpret children’s well-being and mental health, and taking a developmental approach is important as it helps us to spot and interpret a number of different patterns and behaviours. Furthermore, looking at developmental outcomes (milestones) allows us to see when development is atypical and helps us to identify ways in which the child may need supporting. Children are qualitatively different from adults, they are not born as mini adults, and they are not born as empty vessels. They are complex in their development: some development occurs slowly and over time; other times development occurs rapidly such as in infancy and adolescence. To help, we can break it down into the following phases of development:

There are also different aspects of development:

Of course, the child develops as a whole and the different aspects of development do not occur in isolation. They all interact with one another. To understand this we look at patterns of development. Development isn't always progressive. There are various patterns of continuous change. Sometimes development can be very rapid and sometimes change is slow and gradual. At 18 months children start to engage in pretend play. Pretend play starts to decline during middle childhood as other forms of play become more prominent. This pattern of continuous development is often known as an inverted U function; where you can see that development increases and then declines. You can also have U shaped continuous change where you see an apparent decline that actually leads to an improvement in development. Often this is true of cognitive development where a child’s behaviour may look like it is becoming more difficult but actually, cognitively, they are re-evaluating how to perform the task and then their performance improves. Another pattern of development is stage changes. This is where you have changes in ability which seem to take quite a dramatic shift. A classic theory of stage changes is Piaget’s theory of development. He outlined four stages of cognitive development:

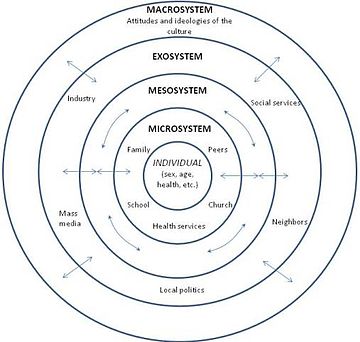

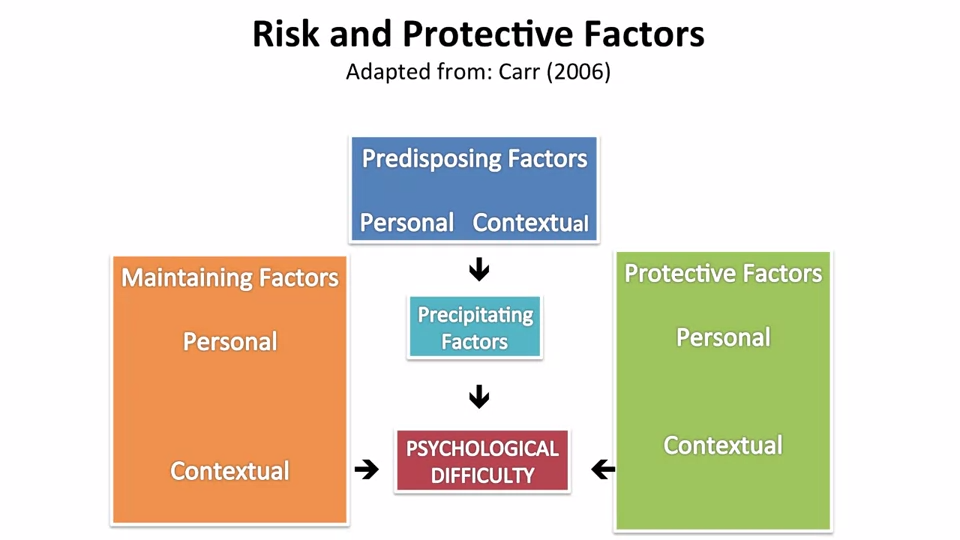

Piaget argued that each of these stages is typified by a new range of cognitive abilities or operations that allow children to cognitively perform at a different level. There are many influences on development. Firstly, biological influences like genetics and the brain. Genetics have a probabilistic relationship with development. They do not always determine or cause different developmental outcomes but they influence it through interacting with other genes and other things in our environments. An example of where genetics do have a direct link with development is in Down Syndrome. It’s a chromosomal abnormality that lead to a particular set of features and characteristics. Most genetic contributions are, however, probabilistic and they are seen as a risk or protective factors rather than direct causes. Twin research studies have been helpful in assessing the relative role of genes versus environment. As a result some mental health conditions and difficulties have been found to have a genetic component to them. For example, schizophrenia, ADHD, Autism, developmental dyslexia. However, genes aren't the whole story they are just a part of it. The Human Genome Project has helped to identify which genes or constellation of genes influence particular developmental and mental health outcomes. For example, we now know particular genes are involved with autism. We also know that some genes and combinations of genes act as protective factors as well. Brain development is also a significant biological influence. We know that there are important growth spurts which occur in the brain, firstly in infancy, and then later in adolescence. In the first two years of life we know that the brain grows enormously; but even more important are all the connections that are made in the brain that are related to the experiences the child has both physically, socially and emotionally. The more experiences a child has the more connections are maintained. If those experiences don’t occur or are reduced then the synaptic connections are pruned. This means that early brain development in infancy is very much a product of the environment the child is in; but in turn that brain development itself offers developmental opportunities for the child. The next major changes in brain development occur in adolescence which coincide with puberty. I’ll write a separate post on this later. Biological influences are really important but the environments within which children live and the people they live with are crucial to their development. We refer to these as social and environmental factors. Not only do the people a child lives with influence the food they eat (whether they have enough), the house and community they live in but also the people around them give them opportunities to learn and improve their understanding of the world and themselves. Also the people around them help them to form relationships and emotional bonds with others which can last in the long term. Social workers can use a tool (based on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological systems theory) to assess a child’s social and environmental factors. A child can complete a task with concentric circles with them in the middle; identifying who they think are important to them. Most importantly you should ask the child why they feel they are important. The third influencing factor on development is the interactions between biological, psychological and social influences. Most of a child’s development is influenced by both biological and social factors and how they interact. This area is often called the nature / nurture debate. For example, in early infancy, experiencing a loving, caring relationship with someone is crucial to the development of attachments. If this area is of particular interest you might like my posts on Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nurture and Nurture. Finally, we looked at models of developmental psychopathology and it’s influences on mental health and well-being. Developmental psychopathology focuses on normal and abnormal development and also adaptive and maladaptive processes. It shows us that there are a range of developmental trajectories that a child can take. Compas and colleagues undertook a review of adolescent development and highlighted that there isn’t just one developmental pathway or trajectory. They identified five:

This model is important as it highlights that adolescent development doesn’t just have one pathway. There are a range of different pathways that young people can find themselves on depending on a range of different factors and influences. Social Workers work with children and use skills based upon child development in their everyday practice. We observe children and learn something about how they’re developing and their well-being from our observations of them. We speak to children and learn about their development directly from them. We sometimes use little tasks and drawings and even short questionnaires and scales. If you'd like to find examples of scales and questionnaires that might be helpful in your practice please take a look at the tools section of this website.

Next week I'll be covering the topic of resilience. Please follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss it! |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|