|

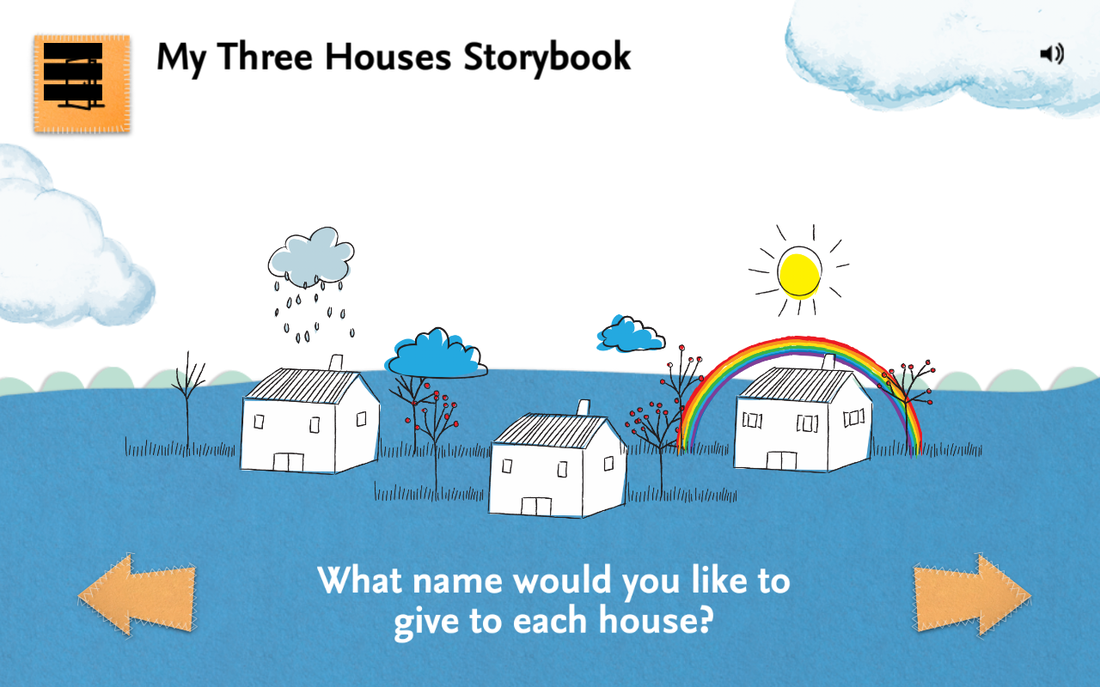

In 2010/11 Professor Eileen Munro reviewed the English children’s services system and found organizations and workers had become over-bureaucratized and compliance driven at the expense of direct work with families, parents and children. Following the recommendations of the Munro review, the UK government launched a Children’s Services Innovations programme which, amongst other things, has financed the development of a new app for social workers to use in their practice with children and families. Developed in Western Australia and designed with children’s services practitioners in UK, USA and Australia, the My Three Houses App offers a tool that taps into children’s love of all things iPad and encourages them to speak about what is happening in their life. The three houses tool was first conceived in New Zealand in 2003 and since then has been used by social workers all over the globe to place the voice of the child at the centre of child protection assessment and planning. I've blogged about using the analogue version here. This app brings the tool into the digital realm. There's video... Interactive animation... and a drawing pad for children.

0 Comments

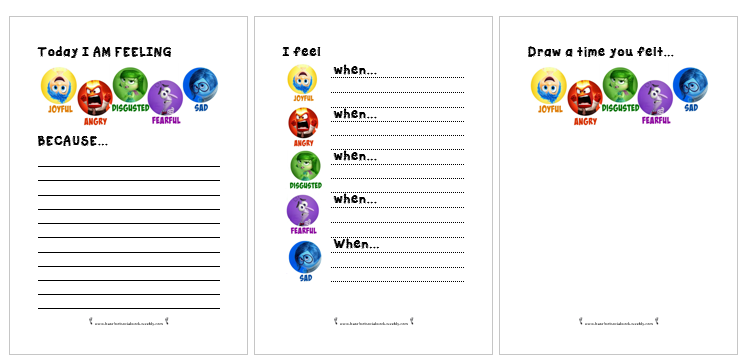

A year or so ago, I remember reading an article on The New Social Worker by Addison Cooper about ‘How Movies Can Help in Working with Kids’. If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do. It won’t take very long. Basically, she talks about how ‘movies can provide an excellent and easy way to connect with clients’ and ‘provide them with understandable analogies’. I think most Children’s Social Workers draw upon popular culture in their work. Cbeebies characters provide a universal conversation starter for most pre-schoolers and The X Factor is usually good with Teens. But we can also, as Addison points out, use them to help children understand their own emotions and circumstance. This summer’s movie Inside Out has received fantastic reviews and looks like a brilliant resource and tool for Social Workers. Take a look at the trailer if you haven’t already seen it. An article in The Guardian calls it a crash course in PhD Philosophy of self. It tells the story of 11 year old Riley, who moves to a new city and tries to make sense of her environment. The central characters Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust live in Headquarters, the control centre inside Rileys mind. Of course, in reality, there are more than just five emotions but that would have made the storyline a little too complicated. Whilst initially viewers may perceive most to be negative emotions, as the movie progresses we see how they work together and play an important role in keeping Riley safe. A message that Social Workers will understand and be able to relate to in their practice. During one scene Joy tells Sadness, drawing a small circle around the blue character, “your job is to make sure that all the sadness stays inside of it”. I find this quite profound as it is often what we see children encouraged to do when they are struggling with their emotions. Sadness and Anger can manifest in all sorts of ways that society perceives to be negative. Schools and classrooms aren't always set up to deal with the individual emotional needs of a pupil when their behaviour is seen to be impacting upon the learning of others around them. So, they are encouraged to ‘behave’, ‘be quiet’ and ‘calm down’. Hopefully Inside Out will help others to interpret children’s actions and foster empathy. It might also resonate with parents struggling to understand their child and how they can best support them. I’ve put together a couple of resources that you might like to use. Please feel free to download and share. Amazon also sell figures that could be incorporated into direct work or you can print off some of the colouring pages from the Disney website.

Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

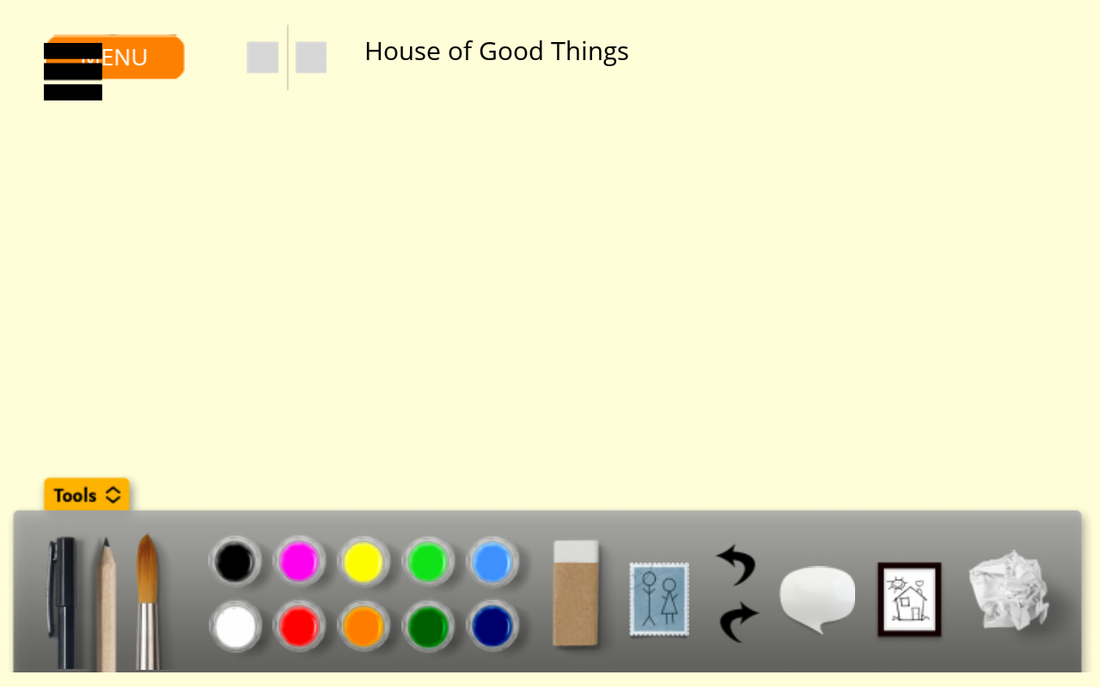

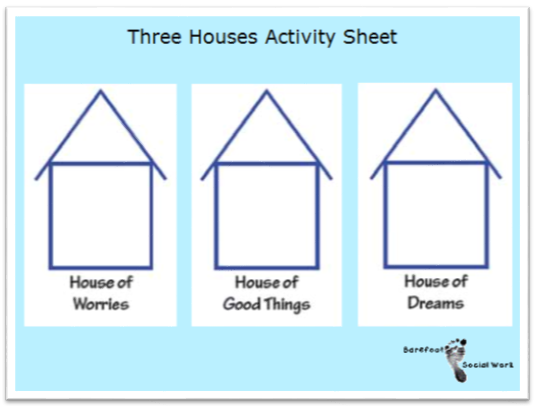

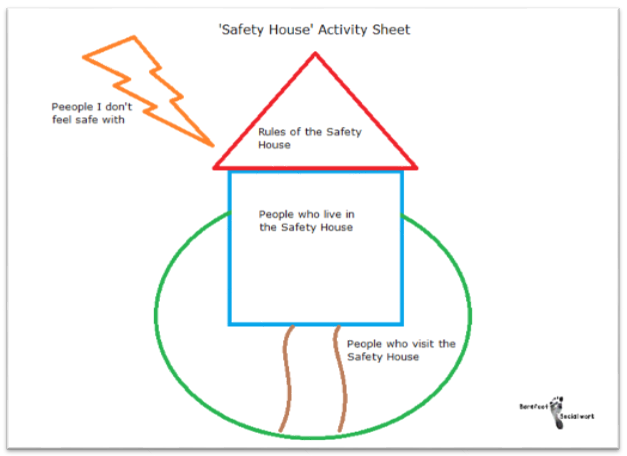

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.  The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred” system was for social workers to have the time and the skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. NICE has also recommended that professionals take greater steps to actively involve children and young people in the process of entering care, changing placement, or returning home and a series of intervention tools should be considered to help guide decisions on interventions for children and young people. What this means is that there is a general consensus that there should be a greater focus on direct work in professional practice. Direct work with children is a complex skill to master but the techniques can be relatively simple. Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective in the past. In most cases all you need is pen, paper and time. The 'Three Houses' technique was created by Nicki Weld and Maggie Greening in New Zealand (Weld 2008, cited by Turnell 2012) and is mentioned in the Munro review. It helps a child or family think about and discuss risks, strengths, and hopes. It is usually most effective with older children or with families where you are finding it difficult to devise an effective intervention plan and can be used with individuals or a group. Taking three diagrams of houses in a row, Social Workers explore the three key assessment questions: 1) What are we worried about, 2) What’s working well and 3) What needs to happen/how would things look in a perfect world. Start by presenting the three blank houses to the child or they could draw their own. Beginning with the ‘House of Good Things’, the child is asked what the best things are about living in the house and questioning is directed around positive things that the child enjoys doing there. After this stage you should progress to discuss the ‘House of Worries’ and find out if there are things that worry the child in the house or things that they don’t like. Finally the ‘House of Dreams’ covers an exploration of thoughts and ideas the child has about how the house would be if it was just the way they wanted it to be. A description is built up detailing who would be present and what types of behaviours would occur. The ‘Safety House’ tool was developed by Sonja Parker. It helps to represent and communicate how safe a child feels in their own home and what could be done to improve things. It can be used with children who are not currently living with parents in order to plan for reunification. Progress can also be assessed by changes in the safety house drawing and can be a key tool in the assessment of risk and safety planning. Start with a picture of a house with a roof, path and garden. The house and garden are divided into sections and the child can describe who they would like to live with them, who can visit and stay over and who is not allowed to come into the house. Safety rules are devised and put into the roof of the house and details of what happens in the house and what people do can be discussed. The house can also be utilised as a readiness scale by using the path as an indicator of how ready they are to return home.  The faces technique involves asking the child to pick from a range of different facial expressions and assigning them to members of their family. It is a useful method for discovering how a child perceives their family and is likely to appeal to younger children or those at an earlier stage of development. After explaining to the child that you want to know more about their family, show them some pictures of different facial expressions, making sure they understand each expression and the emotion it relates to. You could draw them yourself or use a professional set. I recommend the Todd Parr Feelings Flash Cards which are really attractive and accessible for young children. They’re also thick, sturdy and, most importantly, durable. For more developed children, you can select a wide range of expressions; for those at earlier stages of development, you might want to just use two or three (ie happy, sad and angry). There are many other activities that are effective in direct work with children and young people. I will try to write more posts soon. Follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss them! In the meantime, you might like to take a look at Audrey Tate’s book, Direct Work with Vulnerable Children. It’s primarily a set of playful activities to create opportunities to engage children. Through these activities children are enabled to tell their stories and provide Social Workers with assessment and support opportunities. A couple of weeks ago I was asked about the causes, symptoms and likely consequences of troublesome and antisocial behaviours in children and young people. I’ve put together this post to offer a little bit of insight and advice to parents and those working with children displaying these kinds of behaviours. I hope that this post will help you by:

Nearly all children and young people can react in an angry or aggressive way if they are provoked. This ability is essential for survival, otherwise people would have difficulty defending their need for space and food. That is not what this post is concerned with; rather we are looking at cases where children are aggressive and angry a lot of the time. Children that do this far more than others, and in a way that prevents them from making satisfying relationships and getting on with activities and schoolwork. Before we get started I think it is important to firstly distinguish antisocial behaviour from the following: Occasional acts of antisocial behaviour or temper outbursts, once a fortnight or month, can be very frustrating for parents or teachers. However, if the child is well adjusted, has friends and is doing okay at school: adults should react calmly and not make too big a deal of what has happened; respond quietly (shouting at the child and calling them names can do more damage than the child’s original outburst); stay calm and apply a consequence that lasts a short time but is important to the child (for example, taking away a mobile phone, grounding the child or stopping them watching TV); talk when both sides have calmed down, about what happened and try to find ways to stop it happening again in the future. New antisocial behaviour in a previously well-adjusted child. This could include longer periods, up to a month or two, of aggression and moodiness in a previously reasonably adjusted child that after investigation seems to have a fairly obvious cause for the change in behaviour. For example: separating parents, failing an exam, breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend, moving to a new area or being bullied or abused. In these cases, adults should find a calm moment to talk to the child and discover what is on their mind; suggest possibilities to the child, as he or she may not be aware how upsetting an event has been; make the child feel that they are understood and there is sympathy for them; once the causes has been agreed, make plans for a more positive future. Usually the behaviour will settle down; if it doesn't, then a more significant problem should be considered. Long-standing antisocial behaviour can be defined as a general pattern of antisocial behaviour that has been present for several months in children and young people. In younger children this pattern can include: being touchy, having tantrums and being disobedient; breaking rules, arguing and rudeness; deliberately annoying other people, hitting, fighting, and destroying property around the house or school; or, bullying other children. If the pattern is persistent and serious enough to reduce the child’s ability to have a happy home life and/or get on at school, then the child is likely to meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. In older children and teenagers this pattern can include: lying and stealing (including breaking and entering into houses) and cruelty to other people or animals; leaving the house without saying where they are going (staying away overnight without permission); skipping school (truancy) or breaking the law, drinking alcohol inappropriately or taking drugs inappropriately; being a member of a gang and/or carrying a weapon. If the pattern is persistent and serious they are likely to meet criteria for a conduct disorder. The long-term consequences of a conduct disorder are often negative and the child may be at significant risk of: criminal and violent acts; misusing drugs and alcohol; leaving school with few qualifications; or becoming unemployed and dependent on state benefits. It is, therefore, important that those working with children and young people are able to identify those who are at risk so that effective interventions are available. If you are worried a child is displaying signs of oppositional defiant disorder or a conduct disorder you should seek a referral to CAMHS through the child’s GP. Many children and adolescents behave in a difficult or aggressive way from time to time. However, a minority do this persistently for several months in a way that hurts other people emotionally or physically. This can result in poor relationships with family, friends and peers at school. Young children may be very difficult to handle at home but perfectly well behaved at school. A small minority are the other way around. If problems persist they often spill out from home to include school and relationships with friends, who get fed up with the aggression. Bullying, for example, may happen during the school day or on the journey to and from school. Teenagers may go out into the local community in gangs and commit antisocial acts. There are many possible underlying causes of persistent anti-social behaviour. The first step in assessment should be to speak with the child or young person about their behaviour as well as any upsetting external events in their life. Parents and teachers are also a great source of information and insight regarding a child’s well-being. If a child has been performing worse than expected in school, it may be that they have a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia with reading. It is not necessarily the case that poor performance is due to laziness and failure to apply themselves. If a child is restless and fidgety, has difficulty sitting still and moves around more than other children, it is possible that they suffer from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). If present, the child will also have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating. They will not be able to control themselves in a wide range of situations such as queuing up at school, or taking turns in conversation. Schools should be able to refer children displaying these behaviours for assessment by an educational psychologist. If a child is persistently sad and miserable, it is possible that they are suffering from depression. If this is a concern you should request additional support through your GP. You may also find my article on Attachment Based Family Therapy useful. Ineffective parenting is often a strong contributor, particularly if there is little warmth or positive encouragement; low involvement and poor supervision of the child’s activities and whereabouts; inconsistently applied consequences; or negative and harsh discipline. Certain types of parenting are more likely to lead to antisocial behaviour either initially, or in maintaining it. For example, through inconsistent discipline the child may learn that they often get what they want by misbehaving, which in turn reinforces the behaviour. In many cases it may be that parenting is not ‘ideal’. This may arise simply out of exasperation, where the child is so annoying that the parents lash out angrily. Even if the original cause of the behaviour was an unhappy event, or a difficult temperament, if the child learns that he or she is rewarded by getting what they want through misbehaving they will do it more often. When children get little attention, they prefer to have negative attention than none at all. They will misbehave to gain the interest of the parent, even if through scolding or telling off. Reversing it provides a way forward for treatment. The way to reverse bad behaviour is to help parents build a positive relationship with their child. The parent should be supported in making clear the behaviour they want from the child and reward them through attention, praise or other good things. When the child does not behave, parents should use calm limits with clear consequences. Minor misbehaviour should be ignored whilst there should be proportionate consequences if it is more serious. Children must be given plenty of attention and encouragement for positive behaviour. This means instead of saying ‘stop running’ say something like “please walk slowly”, or “I really like it when you walk calmly”. If the child is making a mess at the dinner table, rather than saying “stop making such a mess”, you should give clear instructions as to what is desired and then praise them. These instructions are very clear and help the child understand what is required. Praise should be immediate as it allows the child to see a clear link between cause and effect. Barefoot Social Work can provide support on effective interventions, and an action plan can be formulated for your child or young person. Usually these work by helping parents and others around the child set clear limits and encourage positive behaviour. However, sometimes they can also help the young person learn techniques to control their temper. It may be that parenting classes will be beneficial or a period of intensive one-to-one parenting support. Please get in touch if you require any additional advice. Finally, it is important to note that if behaviour is suspected as being the result of abuse it is essential that concerns are reported to your local authority children’s safeguarding service. Adolescent 'behavioural problems' are a huge source of referrals for local authority children's services across the country, after parents and teachers struggle to find strategies that work. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that many rebellious and unhealthy behaviours or attitudes in teenagers can actually be indications of depression. The following are just some of the ways in which teens “act out” or “act in” in an attempt to cope with their emotional pain:

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) has been the traditional route for support in the UK. However, waiting times and thresholds are at an all time high. More and more services are commissioned only for those children presenting with the signs and symptoms of a diagnosable disorder or condition which means that those struggling with less obviously acute or harder-to-label problems are often not eligible for treatment. As a result Children’s Social Workers are increasingly working to help families through what can be a very distressing time, and there is a renewed focus on specialised training to meet this need.  Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) is a manualised, empirically informed, family therapy model specifically designed to target family and individual processes associated with adolescent depression. However, I have found it has strong applicability when working with all families with teenagers. It was first developed by Prof. Guy Diamond, Suzanne Levy and Gary Diamond; all of whom have received international acclaim for their work in this area. The model is emotionally focused and provides structure and goals; thus, increasing the Social Workers intentionality and focus. It has emerged from interpersonal theories that suggest teenage depression can be precipitated, exacerbated, or buffered against by the quality of interpersonal relationships in families. It is a trust-based, emotion focused model that aims to repair interpersonal ruptures and rebuild an emotionally protective, secure-based, parent-child relationship. Teenagers may experience depression resulting from the attachment ruptures themselves or from their inability to turn to the family for support in the face of trauma outside the home. The aim of ABFT is to strengthen or repair parent-child attachment bonds and improve family communication. As the normative secure base is restored, parents become a resource to help their child cope with stress, experience competency, and explore autonomy. I believe it should be integrated into the practice of all children’s social workers. If you’d like to learn more you can buy the latest book, Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Depressed Adolescents, here. Play dough is an excellent aide for working with Children but when you are using it with multiple clients it can quickly become mixed up and dry out. I don't know about you, but whenever my kids are playing with the bought stuff I get a bit annoyed when it becomes a mangled mess of colour within seconds. That's why I make my own. It's so cheap, easy and quick to do. Because of this, I really don't mind replacing it more frequently. To make your own you will need: 1 cup of flour 1 cup of water 1 cup of salt 1 table spoon of oil 1 table spoon of Cream of Tartar Food colouring (Supermarkets only seem to stock 10g sachets of Cream of Tartar nowadays so I buy mine online as it works out cheaper that way and lasts 'forever') Heat the water, oil, salt, and food colouring. Once it starts to boil take it off the heat and stir in the flour. Once all the ingredients are combined, knead the dough until you reach the right consistency. Be careful though as it will still be quite hot! Using Play Dough in Direct Work There has been much research into the fact that both children and adults are more open and honest when they have something to hold. That's why I always accept the offer of a brew when making visits to clients. They are likely to make one for themselves at the same time but you don't have to drink it if your not really a tea drinker. I've also mentioned before that children are often more willing to open up when they are engaged in an activity. Play dough can be used for it's sensory qualities, giving children something malleable to hold and squish in their hands whilst you explore issues affecting them and their family. To use in direct work set up a simple invitation to play in a quiet room where you are unlikely to be disturbed. The last thing you want is for someone to walk in looking for a stapler when you are on the brink of an emotional disclosure.

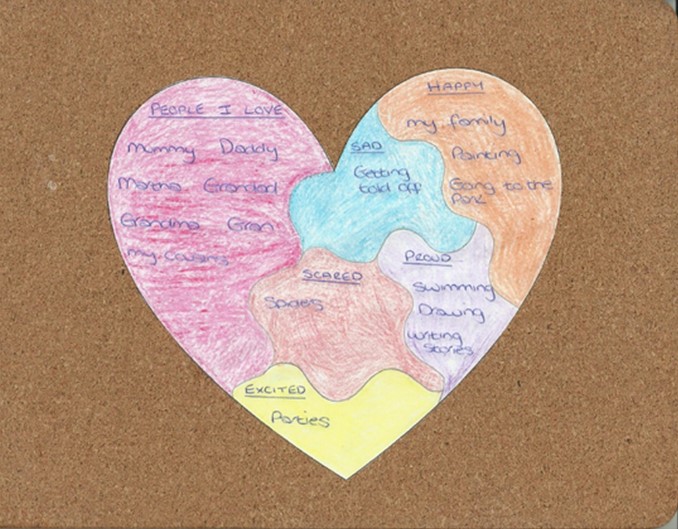

You can also use play dough in directive play for a specific assessment purpose. Children could be encouraged to create themselves or others out of play dough. This is a variation on the draw-a-person technique and should be interpreted in a similar way. This is a brilliant activity to do with new clients. Children, in particular, find it useful to have a visual aide when talking about their emotions. The one above is a very simple illustration. You can include as many or as few sections as you wish, assigning appropriate labels depending upon the child's particular circumstances. It's a great way to find out about who is important to the child and what is happening in their life. I would recommend guiding the child through the activity before inviting them to colour each section whilst you explore any issues raised further. Children often feel more comfortable opening up when they are engaged in a simple activity.

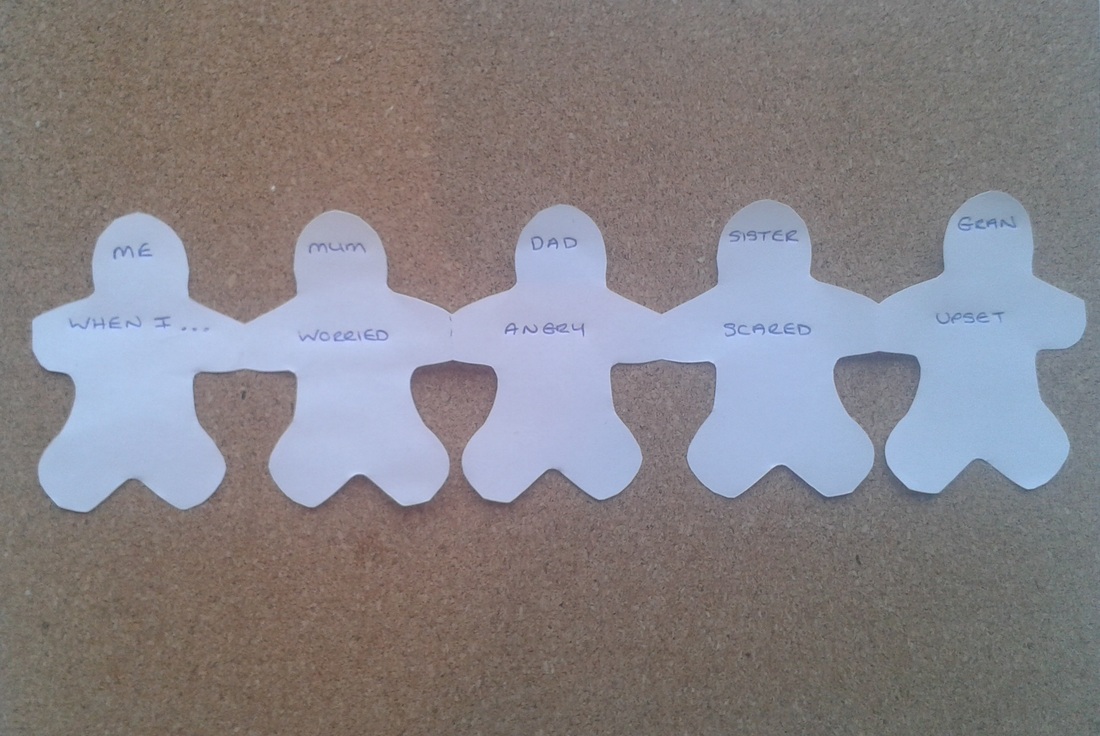

It is important to be mindful of the fact children sometimes offer answers that they believe are expected instead of what is true for them. For example, when completing the example above, my daughter said "my family(?)" when asked what makes her happy. I have no doubt that family brings her great joy, however, she offered the answer as a question, seeking my reassurance that this was the right response. Professionals are usually acutely aware of this behaviour and should be reflected in any analysis of the results. Unlike intelligence and physical attractiveness, which depend largely on genetics, empathy is a skill that children learn. Although the best training for empathy begins in infancy, it’s never too late to start. Infants and toddlers learn the most by how their parents treat them when they are grumpy, frightened, or upset. By the time a child is in preschool, you can begin talking about how other people feel. When working with children and young people whom display complex and/or challenging behaviour I have used paper dolls to encourage them to think about how their behaviour impacts upon others and visa versa. The activity can be used in several situations and also with adults. It doesn't have to be about discussing negative behaviour. You could also use it as an opportunity for families to share pride in one another's achievements. Some families find it difficult to share emotions with one another. In this instance you might write a child's recent achievement on the first doll before passing it to other members of the family to complete their own, describing how they feel.

Another idea might be to use it as an opportunity for children to voice their feelings about a parents behaviour during child protection cases. The end result will provide the parent with a visual reminder of how their choices impact upon their children's welfare. Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991) is a way of talking with people about change that was first developed for the field of addictions but has broadened and become a favoured approach for use with a wide variety of populations in many different settings. It complements the strengths based approach that is gaining in popularity and engages clients as agents of change.

Typically, in child protection parents motivation for change is presumed to be static. They either possess it or lack it and there is very little the Social Worker can do to change this. Under these conditions the Social Worker becomes a punitive enforcer of court orders and agency rules and regulations and does little to promote change. Under the threat of punitive measures parents are asked to change or else. However, it is well documented that a confrontational counselling style limits effectiveness. Miller, Benefield and Tonnigan (1993) found that a directive-confrontational counselling style produced twice the resistance, and only half as many “positive” client behaviours as did a supportive, client-centred approach. The researchers concluded that the more staff confronted substance-involved clients, the more the clients drank at twelve-month follow up. Problems are compounded as a confrontational style not only pushes success away, but can actually make matters worse. By using Motivational Interviewing interactions become more change focussed and relationships between families and Social Worker become more collaborative. The technique should be used simultaneously with other protective measures to ensure that children are safeguarded from the risk of significant harm. I trained to use motivational interviewing whilst working with an offending and addiction service in 2007. I have since found the technique to be hugely beneficial when applied to work with children and families. If you would like to learn more, Motivational Interviewing in Social Work Practice is an excellent book providing an accessible introduction to MI with examples of how to integrate this evidence based method into direct practice. You can also find some useful MI tools on my website.  Simple tools and quesionnaires are a little unpopular with Social Workers, which is a pity, because if used correctly they can add value to the assessment process. I have just uploaded a copy of the Parent Concerns Questionnaire to the tools section of my website so that you can download it and use in your practice. It was originally developed in 1999 by Michael Sheppard, a professor of Social Work at Plymouth University, to research maternal depression. Since then it has been adopted and used by practitioners across the sector. It is based upon the Common Assessment Framework and takes approximately 10 minutes to complete and can be used as a starting point for discussions between parent and practitioner. However, it goes without saying that Social Workers should not rely too heavily on it and ensure that they continue to use their objectivity throughout the assessment process. There are also a number of other resources for you to download. Take a look and let me know what you think. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|