|

A year or so ago, I remember reading an article on The New Social Worker by Addison Cooper about ‘How Movies Can Help in Working with Kids’. If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do. It won’t take very long. Basically, she talks about how ‘movies can provide an excellent and easy way to connect with clients’ and ‘provide them with understandable analogies’. I think most Children’s Social Workers draw upon popular culture in their work. Cbeebies characters provide a universal conversation starter for most pre-schoolers and The X Factor is usually good with Teens. But we can also, as Addison points out, use them to help children understand their own emotions and circumstance. This summer’s movie Inside Out has received fantastic reviews and looks like a brilliant resource and tool for Social Workers. Take a look at the trailer if you haven’t already seen it. An article in The Guardian calls it a crash course in PhD Philosophy of self. It tells the story of 11 year old Riley, who moves to a new city and tries to make sense of her environment. The central characters Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust live in Headquarters, the control centre inside Rileys mind. Of course, in reality, there are more than just five emotions but that would have made the storyline a little too complicated. Whilst initially viewers may perceive most to be negative emotions, as the movie progresses we see how they work together and play an important role in keeping Riley safe. A message that Social Workers will understand and be able to relate to in their practice. During one scene Joy tells Sadness, drawing a small circle around the blue character, “your job is to make sure that all the sadness stays inside of it”. I find this quite profound as it is often what we see children encouraged to do when they are struggling with their emotions. Sadness and Anger can manifest in all sorts of ways that society perceives to be negative. Schools and classrooms aren't always set up to deal with the individual emotional needs of a pupil when their behaviour is seen to be impacting upon the learning of others around them. So, they are encouraged to ‘behave’, ‘be quiet’ and ‘calm down’. Hopefully Inside Out will help others to interpret children’s actions and foster empathy. It might also resonate with parents struggling to understand their child and how they can best support them. I’ve put together a couple of resources that you might like to use. Please feel free to download and share. Amazon also sell figures that could be incorporated into direct work or you can print off some of the colouring pages from the Disney website.

1 Comment

Historically, up until the 19th century it was asserted that children were simply too young to manifest any symptoms of emotional distress or psychopathology. Rush (1812) said that “the rarity of madness before puberty was because children's minds were simply too unstable for mental impressions to produce more than a transient effect”. Childhood was basically seen as a time before reason could be acquired and, therefore, children were insusceptible to the symptoms and signs of mental anguish and distress. I'm sure you’ll agree that this is an alien notion for any Child Protection Social Worker today.

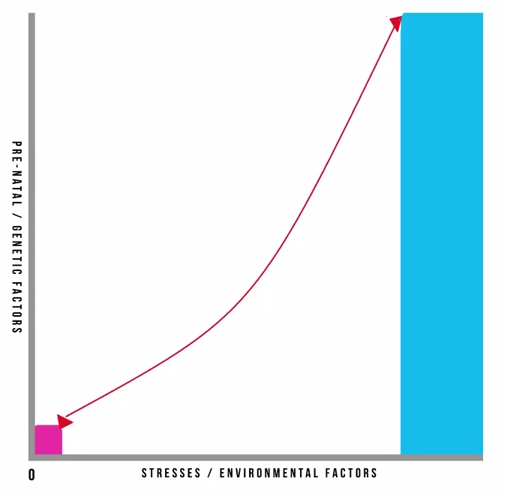

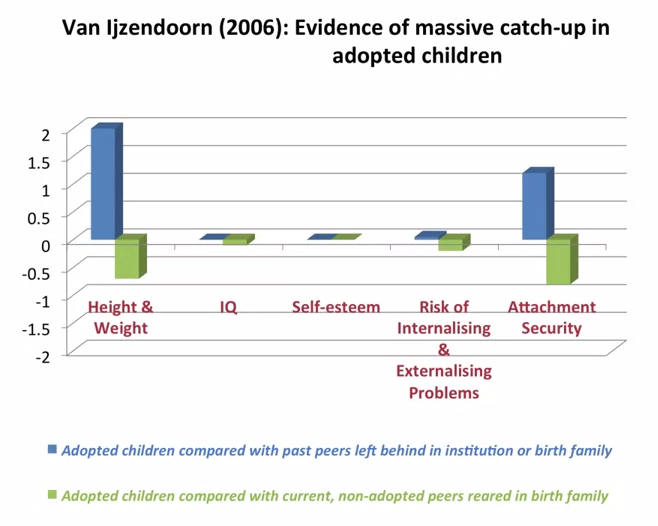

The early 20th century saw the development of a range of scientific and psychological concepts that significantly contributed to our understanding of childhood. I'm thinking of the Formal Assessment and Conceptualization of Intelligence by Binet; the formal cognitive development as outlined by Piaget; the formalization of behaviourism by Skinner and Watson; Freud's theories of psycho-sexual development; and the application of psychoanalytical techniques to childhood by his daughter Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. These developments genuinely created in the early 20th century a community based, integrated, and multidisciplinary approach to child guidance. On the back of a different movement of increasing classification and taxonomy of psychopathology and mental health in adulthood Kranner, in 1935, first coined the term child psychiatry. He used this understanding of childhood and adolescence to try and downward translate taxonomies and classifications developed within adult psychiatry and applied them to childhood and adolescence. Adult taxonomy of psychopathology at the time was purely based on observed behaviours and symptoms that could be described independent of the individual's report. The downward translation into childhood and adolescence proved highly problematic because any manifestation of psychopathology observed by others would interfere and interact with processes of psychological development. The descriptive phenomenology was usually coupled with a perceived and observed decrease in functioning and a stark contrast to so-called premorbid functioning. All of these concepts are highly problematic when applied to childhood and adolescence because they interfere with underlying psychological processes of development. The notion of premorbid functioning needs to be seen in the context of developmental trajectories of the child. Furthermore, the notion of recovery or restitution of premorbid functioning needs to be seen from a developmental perspective. Moreover, the so-called common symptoms and appearances of psychopathology are much more varied throughout childhood and adolescence, and much more tied to the individual's ability and circumstance than they are commonly in adults. So this approach, similar to purely linear or stage models of development, had limited utility for children and adolescents in describing their symptoms and experiences of mental anguish and distress. In addition, not only did this more traditional approach not take account of developmental processes, but it was also based on a much narrower medical model of underlying psychiatric distress. It is also based on a narrow cultural understanding of emotional distress and pragmatically linked to very restrictive and limited treatment options. Professor Matthias Schwannauer states that the more recent changes from a purely categorical approach to a dimensional approach of describing psychopathology, within a classification system, is also not very helpful as the recent dramatic increases in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD in childhood and adolescence demonstrates. It therefore seems that our developmental concepts and boundaries between childhood, adolescence and adulthood need to be re-examined and redefined. We need to take into account societal and cultural changes of what it means to be a child, a young person, and an adult in different societies and reflect on how this impacts on our understanding of mental health, mental well-being, and psychological distress in children and young people. We need to take account of other advances, of other developments in cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional realms to further our understanding of mental health, treatment options and preventative approaches in childhood and adolescence. Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

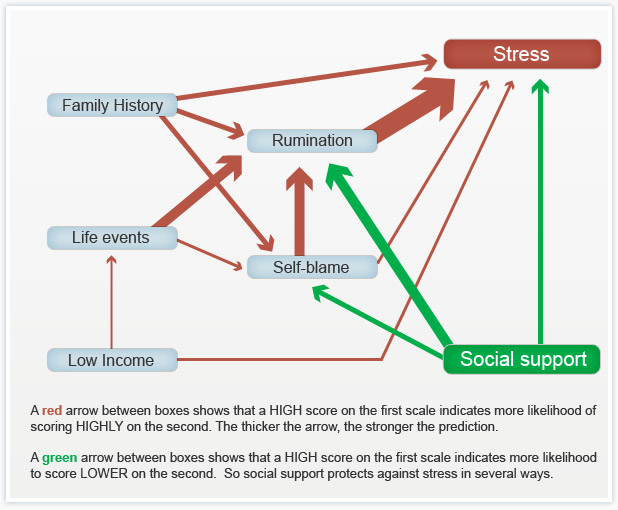

For the last three weeks I've been posting about a course I've been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. This week we focused on the role of psychological mechanisms in the development of mental health problems and the maintenance of well-being. The sources we were presented with suggest that a psychological perspective adds a vital additional element to the ‘nature-nurture’ debate, because it is through these psychological mechanisms that we interpret and respond to the world.  Our course leader Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool, argues that our mental health is essentially a psychological issue, and that biological, social, and circumstantial factors affect our mental health and well-being by disrupting or disturbing psychological processes. The way in which we make sense of the world, the way in which we understand ourselves, who we are as people, the way we make sense of other people, the way that we react socially, how we think about the future, and how we think about the world in general, this sense making, this framework of understanding of the world is fundamentally important in determining our mental health and well-being. To get us started we are provided with a copy of Peter Kinderman’s, A Psychological Model of Mental Disorder. This article discusses the relationship between biological, social, and psychological factors in the causation and treatment of mental disorder. He suggests that a comprehensive psychological model of mental disorder can offer a coherent, theoretically powerful alternative to reductionist biological accounts while also incorporating the results of biological research. We are told that Peter was able to test out some of these ideas in a research study that he conducted with the help of the BBC; testing out the idea of whether a combination of different factors could predict the level of mental health difficulties and well-being that a person was experiencing. They were interested in whether biological factors, which were measured by looking at the experience of mental health problems in a person's family of origin, in their parents and in their siblings, could predict mental health problems, which would then have a variety of psychological and social consequences. Or whether, on the other hand, life events like trauma in early childhood or experiencing a range of negative life events in the last six months would predict people's mental health problems. Or as they hypothesised, whether psychological factors - rumination, where people would go over and over things in their minds, or self blame, where people would blame themselves for the difficulties they were experiencing - would explain more of a person's mental health problems. When they looked at the results, it seemed that social factors were very influential in predicting people's mental health problems, with biological factors playing a part, but a less important part. But importantly, both social and biological factors were mediated by the psychological factors. So, they asserted, rumination and self blame seem to be the gateways towards mental health problems.

You can see the paper itself and also a brief magazine article (Rumination: The danger of dwelling) hosted by the BBC on their website. Peter says that this way of thinking about mental health has some quite profound consequences. If you realise the way in which a person thinks about the world, the way in which a person responds to events in their lives, makes a difference to their mental health, to their well being, to anxiety and depression, it does change the way in which we should approach mental health problems. It brings it back to the idea that how we think about the world matters. Because it changes the way in which we feel and behave. This gives us some different opportunities for how to help people who've got emotional difficulties. But it's also important for people who themselves are suffering, because rather than blaming them for their difficulties, it means that there are things that they can do themselves to get out of the problems that they find themselves in. It gives people a sense of agency and control over their own mental health. Finally we were invited to take part in some of Peter’s current research: Causal and mediating factors in mental health and wellbeing. A follow up study to the research that has formed the basis of this week’s part of the course. At the end of the course we are asked if we believe adding psychological processes to the mix add anything useful to our understanding of the ‘nature-nurture’ debate? Do we think these kinds of factors are important in determining our mental health and well-being? Do we think an understanding of psychological processes mean that we can offer more useful ways of helping people - perhaps through therapy? What do you think? If rumination is posing a difficulty for you or a client there are a couple of things you could try.

I read in the Guardian today that Downing Street have announced Iain Duncan Smith will remain Work and Pensions Minister following the Conservatives electoral win last week. They reported that he will “continue with his task of “making work pay and reforming welfare” as the government implements the universal credit reforms and imposes £12bn in cuts on the welfare budget”. This will be in addition to the £30bn that the Institute of Fiscal Studies say the Tories will also need to find in real-terms cuts from ‘unprotected’ departments, including social care and defence. The news of a Tory win last Thursday didn’t go down well with some. There were large demonstrations in London over the weekend; although it was only the violent clashes with riot police outside Downing Street that seem to have made the headlines. However, the arrests don’t seem to have deterred them; and the anti-austerity group behind the protest are planning another demonstration outside the Bank of England next month. Like many, I am genuinely worried about the proposed cuts and what that means for social work. I posted last week that Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology & Head of the Institute of Psychology, Health & Society at the University of Liverpool, has said that one of the best predictors of mental health disorders by far, whether it’s depression, suicidality, psychosis, are all life events. The strongest predictor all by itself is poverty. Not because poverty by itself causes depression, but because it is a predictor of all the other things that are causal. So poverty has been described as the causes of the causes. And those other causes are a whole raft of things – childhood neglect, childhood abuse, loneliness, and problematic parenting, which is usually inter-generational. It’s not about bad parents, it’s about who themselves haven’t perhaps had the sort of childhood that predisposed them to good enough parenting. And so the cycle continues… There are currently 3.5 million children living in poverty in the UK. That’s almost a third of all children. 1.6 million of these children live in severe poverty. But what the Conservatives don’t want you to know is that 63% of children living in poverty are in a family where someone works. This is why welfare, preventative services, family support and intervention are so vital. We need to break the cycle by providing welfare that brings children out of poverty. Services need to be funded and available to support the most vulnerable and improve parenting so that children can be safeguarded in the care of their family. However, services that were once available have been decimated through cuts over the course of the last parliament and they look set to get worse by 2020. But welfare isn’t just about being a decent human being; it also makes economic sense. In the mid-'90s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discovered an exposure that dramatically increased the risk for seven out of ten of the leading causes of death in the United States. In high doses, it affects brain development, the immune system, hormonal systems, and even our DNA. People that are exposed in very high doses have triple the lifetime risk of heart disease and lung cancer and a 20-year difference in life expectancy. It’s not about eating GM foods. It's childhood trauma: things like abuse or neglect, or growing up with a parent who struggles with mental illness or substance dependence; things that we know, according to Peter Kinderman, are strongly linked to poverty. Take a look at this 2014 TED talk by Nadine Burke Harris. The Adverse Childhood Experiences study found that there was a dose-response relationship between ACEs and health outcomes: the higher your ACE score, the worse your health outcomes. For a person with an ACE score of four or more, their relative risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was two and a half times that of someone with an ACE score of zero. For hepatitis, it was also two and a half times. For depression, it was four and a half times. For suicidality, it was 12 times. A person with an ACE score of seven or more had triple the lifetime risk of lung cancer and three and a half times the risk of ischemic heart disease, the number one killer in the United States of America. Now, you might be thinking – this is interesting but it’s about a study conducted in the United States. Can we rely on the findings to support welfare as a public health initiative in the UK? Well…. In 2014 Mark Bellis and colleagues published a retrospective study to determine the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. They also found that increasing ACEs were strongly related to adverse behavioural, health and social outcomes. Compared to those with 0 ACEs those with 4+ ACEs had a greater risk of poor educational and employment outcomes; low mental wellbeing and life satisfaction; recent violence involvement; incarceration; recent inpatient hospital care and chronic health conditions; and early unplanned pregnancy. All of this suggests a cyclic effect where those with higher ACE counts have higher risks of exposing their own children to ACEs. There are more studies here, here, and here. It’s clear that these childhood experiences place a burden on a UK population’s health, NHS and judicial system; and there is a strong case for the government to invest in effective interventions to prevent them. That’s why the World Health Organization and global health partners are promoting research into the extent and impact of them around the world. So, why is it that during this time of growing evidential support for preventative work, is the government promoting a false economy through welfare cuts and dismantling the welfare system??? In 2007 Lynne Wrennall identified failures in the UK’s work with vulnerable children. She believes that the morale of a “great many caring, compassionate, highly competent, and creative social workers” would be “vastly improved if their primary function was again focused on assisting, rather than dismantling, families, upon working creatively toward this end with the resources and the legislative and managerial support to do so”. However, she also acknowledges that sometimes “an out-of-home placement is unavoidable”, and that in those instances “a programme leading towards re-unification and rehabilitation must be implemented”. She advocates for a “European model” that “strongly favours an educative role for social workers and a primary task of maintaining family unity, utilising and coordinating services toward this end and focusing on `educating’ the parents and family in social norms and values”. But for this to happen the conservative government would first need to reframe the way it thinks about the most vulnerable people in our society and invest in their future wellbeing and health. Local Authorities would need greater funding to hire more social workers so that caseloads are at a manageable level where they have the time to undertake intensive direct work with families again. They would need to fund preventative and outreach services that can directly tackle problems before children become at risk of significant harm. Instead, proposals have been tabled to jail social workers who fail to prevent neglect, despite the necessary infrastructure to properly address it; and the shock result of a Conservative majority victory signals deeper, faster cuts than ever before. Communitycare has urged Social Workers to channel whatever they are feeling about the election result into something that isn’t apathy, because the profession looks set to be needed like never before and I have to agree. P.S. Please follow me on facebook and/or twitter to see posts as they're added to my site

For the last two weeks I've been posting about a course I've been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. So far I've found it really interesting and it has challenged me to reflect on my practice and past cases.

Last week, we discussed the role of biological processes and mechanisms. We were urged to consider how our emotions, thoughts and behaviours are related to neurotransmitter and other biological mechanisms; and to appreciate how this shapes service provisions. This week we were taught about the role of psychological mechanisms in the development of mental health problems and the maintenance of well-being. The material we were presented with highlighted a vital element to the ‘nature-nurture’ debate, asserting that it is through these psychological mechanisms that we interpret and respond to the world. Many psychologists and psychiatrists believe that it's by looking at the nurture side of the equation, by looking at differences between people in terms of the things that happened to them that we can start to explain mental health issues. Our lecturer says that undoubtedly just from the sheer weight of evidence psychosocial events are the more powerful predictor. We heard about Professor John Read, who believes that the best way to explain the origin of mental health problems - and especially differences between people - is by looking at life events and the different experiences we have in our lives. To get things started we are presented with an article from The British Journal of Psychiatry within which Pat Bracken and colleagues set out an argument for a more social psychiatry; arguing that social factors are the most important determinants of our mental health. Here is their 2012 paper if you’d like to have a read yourself. They argue “… that psychiatry is in the midst of a crisis. The various solutions proposed would all involve a strengthening of psychiatry’s identity as essentially ‘applied neuroscience’. Although not discounting the importance of the brain sciences and psychopharmacology, we argue that psychiatry needs to move beyond the dominance of the current, technological paradigm. This would be more in keeping with the evidence about how positive outcomes are achieved and could also serve to foster more meaningful collaboration with the growing service user movement…”. They says that: ”… Although mental health problems undoubtedly have a biological dimension, in their very nature they reach beyond the brain to involve social, cultural and psychological dimensions. These cannot always be grasped through the epistemology of biomedicine. The mental life of humans is discursive in nature. … The evidence base is telling us that we need a radical shift in our understanding of what is at the heart (and perhaps soul) of mental health practice. If we are to operate in an evidence-based manner, and work collaboratively with all sections of the service user movement, we need a psychiatry that is intellectually and ethically adequate to deal with the sort of problems that present to it. As well as the addition of more social science and humanities to the curriculum of our trainees we need to develop a different sensibility towards mental illness itself and a different understanding of our role as doctors…”. Next we looked at a paper recently published in the journal ‘Schizophrenia Bulletin’ by Filippo Varese and colleagues that I found very interesting as a Children’s Social Worker. Filippo and colleagues explored the link between traumatic childhood experiences (poverty, abuse, etc) and later psychotic experiences. We are told that their work was important because many people tend to think that such serious problems as hallucinations and delusional beliefs are quintessentially biological in origin, and this paper suggests an important social dimension. They looked at a wide range of studies that examined the links between life events and later psychosis. Their conclusions were: ”…Evidence suggests that adverse experiences in childhood are associated with psychosis. To examine the association between childhood adversity and trauma (sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional/psychological abuse, neglect, parental death, and bullying) and psychosis outcome … we included 18 case-control studies… 10 prospective and quasi-prospective studies… and 8 population-based cross-sectional studies... There were significant associations between adversity and psychosis across all research designs …. patients with psychosis were 2.72 times more likely to have been exposed to childhood adversity than controls. The association between childhood adversity and psychosis was also significant ... These findings indicate that childhood adversity is strongly associated with increased risk for psychosis…” We are directed to read a paper by Ben Barr and colleagues which looked at how the recent economic recession impacted on suicide rates - a rather dramatic (and sad) example of how social factors impact on our mental health. They found that between 2008 and 2010, there were 846 more suicides among men than would have been expected based on historical trends, and 155 more suicides among women. Next we look at a paper in ‘The Psychologist’ by John Read which expresses some frustration at how attempts to integrate biological, social and psychological perspectives on mental health problems tend tacitly to assume that the most important elements are biological, with the social and psychological elements somewhat downplayed. Read argues that people pay lip-service to the bio-psychosocial model, but undermine it in practice. He gives the example of a senior colleague who: ”…acknowledged some of the recent research about the role of psychosocial factors influencing schizophrenia. He concluded, however, that ‘the schizophrenia wars were over years ago’. He was referring to the truce established under the banner of the ‘bio-psycho-social’ model, which says that schizophrenia is an interaction between a genetically inherited predisposition and the triggering effect of social stressors…” He concludes: ”…The simple truths are that human misery is largely inflicted by other people and that the solutions are best based on human – rather than chemical or electrical – interventions…”. Reading this article I can’t help but remember the men I worked with at a service for ex-offenders with drug misuse issues. Most had a dual diagnosis, a number of them schizophrenia, and all had experienced some form of trauma in their childhood or youth. Each of them received medication to treat the condition but “human intervention” was patchy. Our lecturer tells us that we know following 20, 30 years of research that there is no specific genetic predisposition to any of the mental health disorders. And we know that the best predictors by far of all of them, whether it's depression, suicidality, psychosis, are all life events. The strongest predictor all by itself is poverty. Not because poverty by itself causes depression, but because it is a predictor of all the other things that are causal. So poverty has been described as the cause of the causes. And those other causes are a whole raft of things - childhood neglect, childhood abuse, loneliness, and problematic parenting, which is usually inter-generational. It's not about bad parents, it's about parents who themselves haven't perhaps had the sort of childhood that predisposed them to good enough parenting. This is why preventative services, family support and intervention are so vital. Parents need to be taught and supported to break this cycle; and so that children can be safeguarded in the care of their family. This week’s session has left me with little doubt that I favour the social model (this probably won’t come as a surprise to you as I am a Social Worker and Sociology graduate). I hope that following today’s general election we see a greater investment in mental health services as promised in so many of the parties manifestos. I also hope that the next government values children’s social care enough to invest in it and address the woefully inadequate funding for preventative / support services in this country. Spending cuts and austerity have most definitely fallen hardest on the most vulnerable. Have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on facebook so you don’t miss next week’s post on psychology and mental health. Last week I posted about a course I started entitled Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. Last week's class provided a general introduction to the subject matter and what we should expect from the course over the next few weeks. I was keen to get started.

This week we discussed the role of biological factors - nature - in the development of mental health problems. We heard from Professor John Quinn, who outlined some ways in which neurotransmitter activity affects our moods, and is itself affected by events. We looked at Eric Kandel's 'new intellectual framework for psychiatry'. Eric Kandel is a Nobel prize winning neuroscientist. In addition to his work on memory, Kandel was the author of a very influential and important paper setting out a robust biological account of psychiatry. He argues that all human behaviour, thought and emotion has its roots in the functioning of the brain. Consequently it is to brain-based, neuroscientific, explanations that we should look to for solutions to mental health problems. Kandel argues, in the abstract of his paper, that: ”…In an attempt to place psychiatric thinking and the training of future psychiatrists more centrally into the context of modern biology, the author outlines the beginnings of a new intellectual framework for psychiatry that derives from current biological thinking about the relationship of mind to brain. The purpose of this framework is twofold. First, it is designed to emphasize that the professional requirements for future psychiatrists will demand a greater knowledge of the structure and functioning of the brain than is currently available in most training programs. Second, it is designed to illustrate that the unique domain which psychiatry occupies within academic medicine, the analysis of the interaction between social and biological determinants of behavior, can best be studied by also having a full understanding of the biological components of behaviour…” Kandel then sets out five principles that he believes should provide the underpinnings of a ‘new intellectual framework for psychiatry’. “This framework can be summarized in five principles that constitute, in simplified form, the current thinking of biologists about the relationship of mind to brain.” These are: “Principle 1. All mental processes, even the most complex psychological processes, derive from operations of the brain. The central tenet of this view is that what we commonly call mind is a range of functions carried out by the brain. The actions of the brain underlie not only relatively simple motor behaviors, such as walking and eating, but all of the complex cognitive actions, conscious and unconscious, that we associate with specifically human behavior, such as thinking, speaking, and creating works of literature, music, and art. As a corollary, behavioral disorders that characterize psychiatric illness are disturbances of brain function, even in those cases where the causes of the disturbances are clearly environmental in origin.” “Principle 2. Genes and their protein products are important determinants of the pattern of interconnections between neurons in the brain and the details of their functioning. Genes, and specifically combinations of genes, therefore exert a significant control over behavior. As a corollary, one component contributing to the development of major mental illnesses is genetic.” “Principle 3. Altered genes do not, by themselves, explain all of the variance of a given major mental illness. Social or developmental factors also contribute very importantly. Just as combinations of genes contribute to behavior, including social behavior, so can behavior and social factors exert actions on the brain by feeding back upon it to modify the expression of genes and thus the function of nerve cells. Learning, including learning that results in dysfunctional behavior, produces alterations in gene expression. Thus all of “nurture” is ultimately expressed as “nature.”” “Principle 4. Alterations in gene expression induced by learning give rise to changes in patterns of neuronal connections. These changes not only contribute to the biological basis of individuality but presumably are responsible for initiating and maintaining abnormalities of behavior that are induced by social contingencies.” “Principle 5. Insofar as psychotherapy or counseling is effective and produces long-term changes in behavior, it presumably does so through learning, by producing changes in gene expression that alter the strength of synaptic connections and structural changes that alter the anatomical pattern of interconnections between nerve cells of the brain. As the resolution of brain imaging increases, it should eventually permit quantitative evaluation of the outcome of psychotherapy.” Kandel does not deny that social events are important, but he maintains that social events have their impact on people by affecting the brain: “Viewed in this way, all sociology must to some degree be sociobiology; social processes must, at some level, reflect biological functions. … Nevertheless, it is important to appreciate that there are critical biological underpinnings to all social actions.” Not all psychologists and not all psychiatrists agree with his conclusions, but the paper was definitely worth reading. Next we looked at Nick Craddock and colleagues' 'wake up call for British psychiatry'. Nick Craddock and colleagues drew up a manifesto for the future of psychiatry based at least in part on a biological model of mental health. This 2008 paper was entitled a “Wake-up call for British psychiatry”, and was written by a group of influential and senior psychiatrists. It sets out how a biological model of mental health - the idea that our mental health is determined by our biology - can influence how we design services. Nick and colleagues, in the summary to their paper, argue that: “The recent drive within the UK National Health Service to improve psychosocial care for people with mental illness is both understandable and welcome: evidence-based psychological and social interventions are extremely important in managing psychiatric illness. Nevertheless, the accompanying downgrading of medical aspects of care has resulted in services that often are better suited to offering non-specific psychosocial support, rather than thorough, broad-based diagnostic assessment leading to specific treatments to optimise well-being and functioning. In part, these changes have been politically driven, but they could not have occurred without the collusion, or at least the acquiescence, of psychiatrists. This creeping devaluation of medicine disadvantages patients and is very damaging to both the standing and the understanding of psychiatry in the minds of the public, fellow professionals and the medical students who will be responsible for the specialty’s future. On the 200th birthday of psychiatry, it is fitting to reconsider the specialty’s core values and renew efforts to use psychiatric skills for the maximum benefit of patients”. They begin by arguing that: “… British psychiatry faces an identity crisis. A major contributory factor has been the recent trend to downgrade the importance of the core aspects of medical care”. They argue that this has led to problems: “… In many instances, this has resulted in services that are better suited to delivering nonspecific, psychosocial support rather than a process of thorough, broad-based diagnostic assessment with formulation of aetiology, diagnosis and prognosis followed by specific treatments aimed at recovery with maintenance of functioning…”. and state that: “…Our contention is that this creeping devaluation of medicine is damaging our ability to deliver excellent psychiatric care. It is imperative that we specify clearly the key role of psychiatrists in the management of people with mental illnesses…” Later on, they suggest that: “…In order to follow clinical guidance (such as that provided by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)) to develop excellent ‘mental health’ care (for those with mental illness), it is important to recognise that a biomedical component, with access to appropriate facilities and appropriate service pathways, is usually crucial…”. For Nick and colleagues, this is an optimistic vision: “…Major advances in molecular biology and neuroscience over recent years have provided psychiatry with powerful tools that help to delineate the biological systems involved in psychopathology and impairments suffered by patients. We can be optimistic that over the coming years these advances will facilitate the development of diagnostic approaches with improved biological validity and enhanced clinical utility in terms of predicting treatment response. We can expect that completely novel treatments will be developed based on detailed understanding of pathogenesis…”. … “…Psychological and social interventions will, of course, continue to be crucially important in managing psychiatric illness (as they are also in non-psychiatric disorders). However, in addition, patients have the right to expect that biological factors are fully considered and, where appropriate, evidence-based interventions delivered…”. Thirdly, we looked at 'Chemical imbalances'. One powerful idea in the area of mental health is the suggestion that mental health problems result from ‘chemical imbalances’ and that the psychiatric drugs that are commonly prescribed help people because they ‘correct’ these ‘imbalances’. In fact, if you search online for information about mental health problems that is sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, this idea is very common. Dr Joanna Moncrieff is a psychiatrist who has criticised this approach. In essence, her argument is that psychiatric medication has well-recognised effects on the brain, which affect our moods, behaviours and even thoughts, and which can - sometimes - be helpful for people in great distress. But Jo does not support the idea that these drugs are correcting chemical imbalances; and she describes this as the ‘myth of the chemical cure’. Jo advocates that we adopt what she describes as the ‘drug-based’ model of the action of psychiatric medication, rejecting the ‘disease-based’ approach. This does not mean that she believes that the medication is ineffective. She recognises that the medication has a clear effect on our neurotransmitters, and therefore on our emotions and behaviour. But Jo does not believe that this necessarily means that the medication is correcting an underlying abnormality. Finally we concluded with a brief critique of this weeks’ discussions. We are taught that the science and the logical arguments are both strong: we know that the functioning of our brains lies beneath all our behaviours, thoughts and emotions, and so biological approaches cannot be dismissed. And yet, many psychologists and social psychologists think that biological approaches alone cannot fully explain our experience of mental health problems. Next week, we will be looking at social perspectives on mental health. We are challenged, over the course as a whole, to consider how these different approaches can be integrated and to consider the strengths and weaknesses of the biological component of the ‘biopsychosocial model’. I’ll see you again next week…

I’ve just started a new course entitled Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture by Professor Peter Kinderman (University of Liverpool). The course is largely built on foundations laid down in his two recent books: ‘New Laws of Psychology’ and ‘A Prescription for Psychiatry’.

A Prescription for Psychiatry: Why We Need a Whole New Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing builds from a psychosocial approach to mental health and well-being to recommend a wholesale revision of our mental health services. Arguing that the origins of distress are largely social, and that therefore we need a change from a ‘disease model’ to a ‘psychosocial model’, the book argues that we should reject traditional psychiatric diagnosis, significantly reduce our use of psychiatric medication, tailor help to each person’s unique needs, invest in greater psychological and social therapies, and place mental health and well-being services within a social rather than a medical framework. New Laws of Psychology: Why Nature and Nurture Alone Can’t Explain Human Behaviour proposes a common-sense, cognitive, account of human behaviour - arguing that our thoughts, emotions, actions and therefore mental health can be largely explained if we understand how people make sense of their world and how that framework of understanding has been learned. This approach challenges notions such as ‘mental illness’ and ‘abnormal psychology’ as old-fashioned, demeaning and invalid, argues that diagnoses such as ‘depression’ and ‘schizophrenia’ are unhelpful, and proposes that psychological accounts offer a more helpful way to address emotional distress. This week we are looking at one of the fundamental questions about our mental health; nature or nurture? That could simply mean something like are mental health problems the result of biological processes (nature) or social in origin (nurture)? Are they the result of biological abnormalities or are they the result of life events or other environmental factors? Or, to be a little more specific, is the variance that we see in terms of mental health a result of variance in biological or social factors? That is, can we explain the differences between people’s mental health in terms of differences in biology (different people having different genetics, or different biochemistry) or differences in the experiences they’ve been exposed to? Mental Health featured heavily in the political parties manifestos ahead of the general election in May and it’s right that this area of study and service is given greater priority. As a Social Worker I am acutely aware of the interplay that exists between mental health services and children’s safeguarding. Young Mind is Mind’s youth division. Its website provides the following key statistics about children’s and adolescents mental health:

I’ll post again following next week’s session. Please follow me on facebook so you don't miss it! I can already tell that this is going to be a really interesting and useful course. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|