|

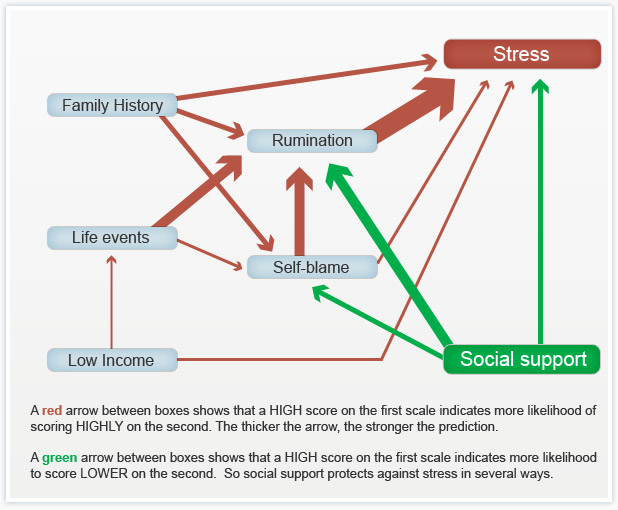

For the last three weeks I've been posting about a course I've been taking called Psychology and Mental Health: Beyond Nature and Nurture. This week we focused on the role of psychological mechanisms in the development of mental health problems and the maintenance of well-being. The sources we were presented with suggest that a psychological perspective adds a vital additional element to the ‘nature-nurture’ debate, because it is through these psychological mechanisms that we interpret and respond to the world.  Our course leader Peter Kinderman, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool, argues that our mental health is essentially a psychological issue, and that biological, social, and circumstantial factors affect our mental health and well-being by disrupting or disturbing psychological processes. The way in which we make sense of the world, the way in which we understand ourselves, who we are as people, the way we make sense of other people, the way that we react socially, how we think about the future, and how we think about the world in general, this sense making, this framework of understanding of the world is fundamentally important in determining our mental health and well-being. To get us started we are provided with a copy of Peter Kinderman’s, A Psychological Model of Mental Disorder. This article discusses the relationship between biological, social, and psychological factors in the causation and treatment of mental disorder. He suggests that a comprehensive psychological model of mental disorder can offer a coherent, theoretically powerful alternative to reductionist biological accounts while also incorporating the results of biological research. We are told that Peter was able to test out some of these ideas in a research study that he conducted with the help of the BBC; testing out the idea of whether a combination of different factors could predict the level of mental health difficulties and well-being that a person was experiencing. They were interested in whether biological factors, which were measured by looking at the experience of mental health problems in a person's family of origin, in their parents and in their siblings, could predict mental health problems, which would then have a variety of psychological and social consequences. Or whether, on the other hand, life events like trauma in early childhood or experiencing a range of negative life events in the last six months would predict people's mental health problems. Or as they hypothesised, whether psychological factors - rumination, where people would go over and over things in their minds, or self blame, where people would blame themselves for the difficulties they were experiencing - would explain more of a person's mental health problems. When they looked at the results, it seemed that social factors were very influential in predicting people's mental health problems, with biological factors playing a part, but a less important part. But importantly, both social and biological factors were mediated by the psychological factors. So, they asserted, rumination and self blame seem to be the gateways towards mental health problems.

You can see the paper itself and also a brief magazine article (Rumination: The danger of dwelling) hosted by the BBC on their website. Peter says that this way of thinking about mental health has some quite profound consequences. If you realise the way in which a person thinks about the world, the way in which a person responds to events in their lives, makes a difference to their mental health, to their well being, to anxiety and depression, it does change the way in which we should approach mental health problems. It brings it back to the idea that how we think about the world matters. Because it changes the way in which we feel and behave. This gives us some different opportunities for how to help people who've got emotional difficulties. But it's also important for people who themselves are suffering, because rather than blaming them for their difficulties, it means that there are things that they can do themselves to get out of the problems that they find themselves in. It gives people a sense of agency and control over their own mental health. Finally we were invited to take part in some of Peter’s current research: Causal and mediating factors in mental health and wellbeing. A follow up study to the research that has formed the basis of this week’s part of the course. At the end of the course we are asked if we believe adding psychological processes to the mix add anything useful to our understanding of the ‘nature-nurture’ debate? Do we think these kinds of factors are important in determining our mental health and well-being? Do we think an understanding of psychological processes mean that we can offer more useful ways of helping people - perhaps through therapy? What do you think? If rumination is posing a difficulty for you or a client there are a couple of things you could try.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|