|

The All Party Parliamentary Group on Runaway and Missing Children and Adults is inviting interested individuals and groups to submit written evidence to its current inquiry into how the police, children's services, schools and other professionals safeguard children who are categorised as 'absent' from home or care or education. The inquiry is intended to examine how the introduction of the ‘missing’ and ‘absent’ categories has affected the safeguarding response to children who run away.

Ann Coffey MP raised concerns about the new absent category in her report published in October 2014 ‘Real Voices – Child Sexual Exploitation Greater Manchester’. The deadline for submissions of written evidence is Friday, 22 January 2016. You can find out more information here. Further reading: Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care. Report from the Joint Inquiry into children who go missing from care (June 2012).

0 Comments

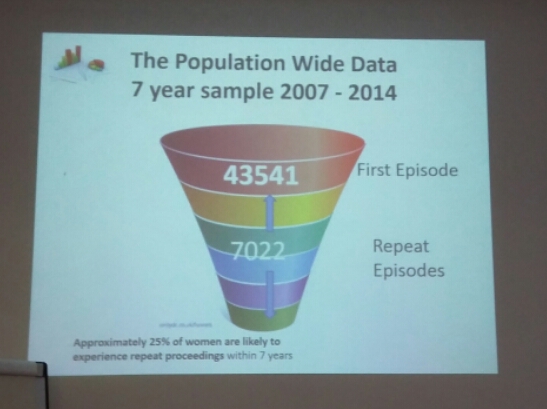

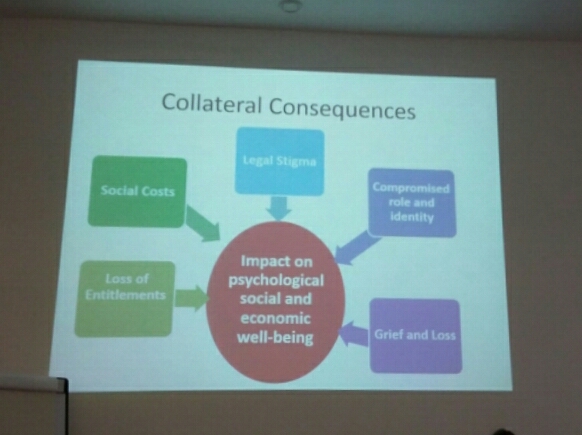

Yesterday I attended ‘Parents’ Voices and their Experiences of Services’ at Friends Meeting House in Manchester. It was an opportunity to examine priorities for system, policy and practice change, drawing upon findings from research and was a very valuable day for reflective practice. The event began with a short introduction by Safeguarding Survivor who chaired the conference with great confidence and professionalism. I know she was nervous but you couldn't tell and she did a brilliant job. If you aren't aware of her story, I recommend you read her blog. It offers great insight into the child protection system from a parents’ perspective and provides excellent advice for others whose children have been identified as ‘at risk’. Her work has been praised for its balance and value by Sir James Munby and you will soon be able to read more of her case after the court granted Louise Tickle (a freelance journalist) permission to publish details in a broadsheet newspaper. You can read the judgement at Family Law.  Siobhann and three mothers from The Mothers Apart project (Women Centre) Kirklees spoke about their book In Our Hearts. It presents open and honest accounts of initial separation, court proceedings, relationships with services, of mothers who have been able to have children returned to their care or contact increased, mothers who have no current contact at all and those for whom contact remains limited. It offers itself up as an aid and guide to learning for parents, families and professionals working in pursuit of child protection. As a result of co-production learning Mothers Apart have developed women centred working that recognises people as assets. Whilst every woman is different they have found that there are a number of common themes and, consequently, much of their work is about power. Sean Haresnape (Principal Social Work Advisor) from Family Rights Group outlined a Parents Charter being developed in collaboration with parents and professionals, that sets out expectations of how services should engage with parents, whose children are subject to statutory interventions; and we heard from Declan, a father and care leaver who had his daughter placed with him following care proceedings. Prof. Karen Broadhurst (Lancaster University) and Claire Mason (ISW & Lancaster University) presented preliminary findings from their 2 year study of birth mothers, their partners and children, within recurrent care proceedings under s.31 of the Children Act in England. The project hopes to confirm the national scale and pattern of recurrent proceedings together with the characteristics and service histories of parents caught up in this cycle. Statistical methods have been used to quantify recurrence and examine the relationship between recurrence and key explanatory variables. This has been complemented by qualitative components that include in-depth interview work with birth mothers in five local authority areas and in-depth profiling of a subset of randomly selected case files. Through data mining they have found that 25% of women who have been through care proceedings will return within 7 years. Teenage motherhood is associated with a significant number of repeat care proceedings and Prof. Broadhurst questions whether the family court is the most appropriate setting for dealing with teenage parents. Another facet of their research looks at the collateral consequences of care proceedings and asks who, once a court case has concluded, is there to support parents with the psychological, social and economic consequences of losing a child. Whilst the child and adopters/foster carers remain supported for a time by Social Workers and other services, there are no statutory support available to parents. This short-sighted approach demonstrates a lack of understanding of the collateral consequences and their cumulative impact which can drive women in to unhealthy relationships and successive pregnancies. In subsequent cases Local Authorities and Courts have been found to act more swiftly and are more likely to remove closer to birth, with adoption being the most likely outcome, compounding the cycle.

Similar concerns were raised last week by Sir James Munby when I attended the annual Family Justice Council debate in London. He said that it was “not fair on subsequent children that post adoption support isn't provided to birth parents” and “there is some substance to the question whether resources are adequately balanced between support for adoption and support for families”. Finally, Prof. Kate Morris (Sheffield University) outlined the empirical research she and Prof. Brid Featherstone (University of Huddersfield) are conducting as part of Your Family Your Voice – an alliance of families and practitioners working to transform the system. Their work, looking at family experiences of multiple service use, highlights the profound difficulty families often find navigating their way through services. At the end of the presentations we were asked to reflect upon what we had heard and identify what changes could be made to make the system a more humane one and minimise trauma for parents, children, their families – and also for practitioners. I invite you to do the same and participate in the research here.

Childhood is a time of rapid change. Some of these changes are obvious, such as height gain, language ability and physical dexterity. Others are less obvious, such as how children make sense of the information in their environment. To understand the rapid changes of childhood, children’s abilities are often judged against developmental milestones, such as acquiring language (babbling, talking), cognition (thinking, reasoning, problem solving), motor coordination (crawling, walking) and social skills (identity, friendships, attachments). But how does digital technology influence the acquisition of these important skills? Does technology hinder a child’s physical, social and cognitive development, or does it provide exciting opportunities for learning?

The entertainment and interactivity of tablets and smartphones has made them attractive to children. Touch-screen interfaces mean that digital technologies are now accessible for children at a very young age. But do children find digital technologies exciting for reasons beyond simple entertainment? The amount of digital technology available to my young daughters is massively different to that in my own childhood. As both a parent and a Social Worker, I've found it difficult to make sense of media reports and research findings in this controversial area. Is technology beneficial or detrimental to child development? Does screen time lead to increased distractibility, obesity and loneliness? Or does it offer opportunities for autonomy and experimentation beyond anything imagined when I was a young child? As the generation gap widens between adults and children’s' understanding of new technologies, how will we protect them from the risks while allowing them to benefit from the opportunities new technologies offer? In 2014 both Ofcom and the NSPCC (Jütte et al.) found that one in three children owned their own tablet. Figures published by the NSPCC also show smartphone ownership increasing with age (20 per cent of 8–11-year-olds and 65 per cent of 12–15-year-olds). These profound changes are reshaping children’s digital environment. The recent EU Kids Online Network project, called Zero to Eight, illustrates just how pervasive technology is becoming for younger children. The project report identified a significant increase over the previous five years of children under nine years old using the internet (Holloway et al., 2013). In particular it noted a growing trend for very young children (pre-schoolers) to use tablets and smartphones to access the internet:

Whilst children are now going online at a younger age, their ‘lack of technical, critical and social skills may pose [a greater] risk’ (Livingstone et al., 2011). The challenge for parents is how best to manage the risks alongside the benefits. I’ll get back to this later…

Children and Digital Technologies Children are often very engaged by digital technology. But why is it so compelling for young children to spend so much time interacting with their digital world? Firstly, technology is fun. Child-centred technology in particular is especially designed to be as entertaining and captivating as possible. Similarly, a big attraction of technology for children is that they see their parents and peers using it, and a major part of childhood is ‘modelling’ the behaviour of those around them, particularly parents: that is, children learn from observing and imitating others around them. Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory (SDT) seems particularly relevant to untangling the reasons behind young children’s fascination with the digital world. According to SDT, there are two overarching types of motivation, ‘intrinsic motivation’ and ‘extrinsic motivation’. The former refers to doing an activity for its own sake because it is enjoyable and this is thought to lead to persistence, good performance and overall satisfaction in carrying out activities. Ryan and Deci outline three basic psychological needs associated with intrinsic motivation that can be applied to children’s use of technology:

Although each of these three basic psychological needs may not be met for every child, the self-determination theory offers a good psychological basis for understanding children’s intrinsic motivation in using technology. According to one study, children are currently spending more time with technology than they do in school or with their families. Similarly, children as young as 2, 3 and 4 are playing with their parents’ phones or tablet devices; and some psychologists argue that this has an enormous impact on their brain development, as well as on their social, emotional and cognitive skills. This raises an important question: in this 24/7 digital world, should parents be setting new rules for their children’s engagement with technology? Should we be promoting new parenting classes for the modern age? Generational Divide The idea of a generational divide between children and adults has been a popular topic among psychologists and sociologists. This has resulted in the use of labels such as the ‘digital native’, the ‘net generation’, the ‘Google generation’ or the ‘millenials’, each of which highlights the importance of new technologies in defining the lives of young people. The most contentious term is the ‘digital native’. The term first appeared in an article by Marc Prensky to describe those children who spend much of their lives ‘online’, constantly ‘switched on’. It represents ‘native speakers’ who are ‘fluent in the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet’. There is a distinction between ‘digital natives’, who are those generally born after the 1980s and are technologically adept and comfortable in a world of technology, and ‘digital immigrants’, who are generally born before the 1980s and are fearful or less confident in using technology. To justify his claims Prensky draws on the widely held theory of neuroplasticity. This means that our brains are highly flexible and subject to change throughout life. The different neural connections in the brain change and evolve throughout childhood in response to the environment. It is claimed that young children’s brains now are developing differently to the way adults’ brains have developed, as children are growing up surrounded by new technologies. This topic of neuroplasticity is something that I have also covered in Risk, Resilience and Adoption. Safeguarding Many parents, teachers and Social Workers have legitimate reasons to worry about children’s engagement with the digital world. We know that children are likely to run risks if they access the internet unsupervised, or stay online for long periods of unbroken time. Examples of the apparent risks appear in the work of Howard-Jones, who analysed current research in neuroscience and psychology. He states that the developing brain can be susceptible to environmental influence, and digital technology opens it to risks including:

You can also find research into internet addiction, aggressive game-playing, grooming and bullying, which have also been linked to children’s exposure to the digital world. Social Media can also present problematic situations for adopted children, and those in foster placements or subject to child protection plans. Even the Pope waded in on the debate earlier this month, warning parents not to let children use computers in their bedrooms because of the 'dirty content' on the internet. Whether you are a digital optimist or pessimist, it’s obvious that while technology brings about opportunities, it also has associated risks. This has led to some professionals arguing that parents should limit young children’s use of, and exposure to, new digital technologies. But is this really the answer? Is simply restricting children’s access actually the best way to ensure their safety? Restricting access to technology may also restrict opportunities for children to develop resilience against future harm and I would argue that simply restricting access or removing technology from children’s lives seems inappropriate (except as a short term measure in cases where technology is presenting a significant risk of harm to the child). Perhaps we need to review parenting methods so we ensure sufficient levels of support for children growing up in this highly digital modern world. If we look at self-determination theory, the idea of giving children autonomy and choice to make appropriate decisions about their own digital world could be the answer. According to some, we need to trust in the maturity and judgement of children. We have to be able to trust their social skills in successfully negotiating these new ways of behaving and successfully managing or avoiding risks (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). It is important to recognise that children’s perceptions of problematic online situations may differ greatly from those of adults. Because of the different perceptions of adults and young people, and the lack of a neat distinction between positive and negative experiences online, many professionals opt to avoid the term ‘risk’, and prefer to talk about ‘problematic situations’. Research by Vandoninck and colleagues, based within the UK, tackles the idea of giving children autonomy to make their own choices. Awareness of online risks motivates children to concentrate on how to avoid problematic situations online, or prevent them from (re)occurring. This brings me to the concept of preventive measures – what children actually do or consider doing in order to avoid unpleasant or problematic situations online. Vandoninck and colleagues identified five main categories of measures discussed in the literature:

Perhaps the key focus of parents and professionals should be on helping children to acquire the knowledge and skills to moderate their own online behaviours; to develop resilience to risks and to become responsible digital citizens of the twenty-first century (Banyard and Underwood, 2012). For more information about safeguarding, take a look at my other posts on online safety and follow me on facebook and twitter. Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

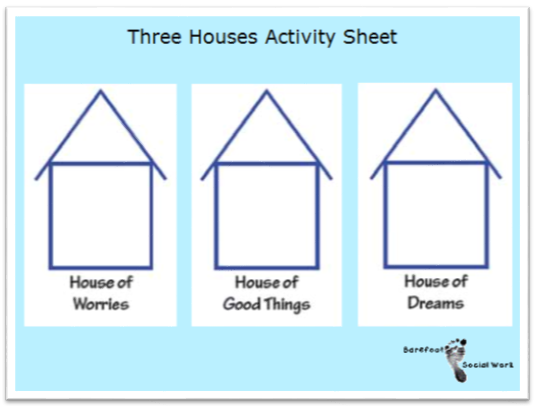

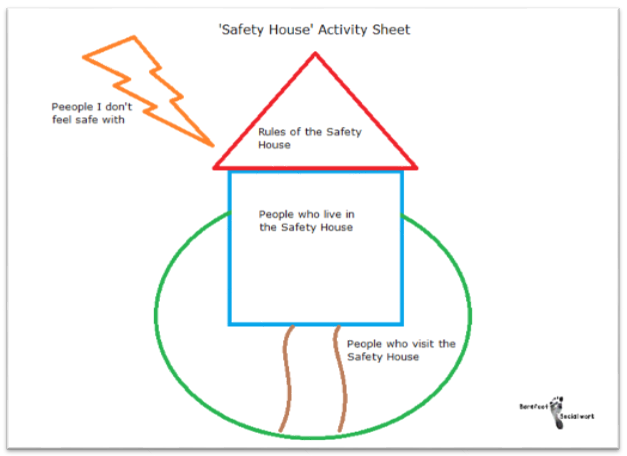

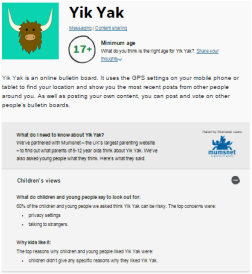

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.  The Munro Review highlighted that the only way to create a “child-centred” system was for social workers to have the time and the skill to undertake a great deal more direct work with children. NICE has also recommended that professionals take greater steps to actively involve children and young people in the process of entering care, changing placement, or returning home and a series of intervention tools should be considered to help guide decisions on interventions for children and young people. What this means is that there is a general consensus that there should be a greater focus on direct work in professional practice. Direct work with children is a complex skill to master but the techniques can be relatively simple. Here are a couple of ideas that I have found to be effective in the past. In most cases all you need is pen, paper and time. The 'Three Houses' technique was created by Nicki Weld and Maggie Greening in New Zealand (Weld 2008, cited by Turnell 2012) and is mentioned in the Munro review. It helps a child or family think about and discuss risks, strengths, and hopes. It is usually most effective with older children or with families where you are finding it difficult to devise an effective intervention plan and can be used with individuals or a group. Taking three diagrams of houses in a row, Social Workers explore the three key assessment questions: 1) What are we worried about, 2) What’s working well and 3) What needs to happen/how would things look in a perfect world. Start by presenting the three blank houses to the child or they could draw their own. Beginning with the ‘House of Good Things’, the child is asked what the best things are about living in the house and questioning is directed around positive things that the child enjoys doing there. After this stage you should progress to discuss the ‘House of Worries’ and find out if there are things that worry the child in the house or things that they don’t like. Finally the ‘House of Dreams’ covers an exploration of thoughts and ideas the child has about how the house would be if it was just the way they wanted it to be. A description is built up detailing who would be present and what types of behaviours would occur. The ‘Safety House’ tool was developed by Sonja Parker. It helps to represent and communicate how safe a child feels in their own home and what could be done to improve things. It can be used with children who are not currently living with parents in order to plan for reunification. Progress can also be assessed by changes in the safety house drawing and can be a key tool in the assessment of risk and safety planning. Start with a picture of a house with a roof, path and garden. The house and garden are divided into sections and the child can describe who they would like to live with them, who can visit and stay over and who is not allowed to come into the house. Safety rules are devised and put into the roof of the house and details of what happens in the house and what people do can be discussed. The house can also be utilised as a readiness scale by using the path as an indicator of how ready they are to return home.  The faces technique involves asking the child to pick from a range of different facial expressions and assigning them to members of their family. It is a useful method for discovering how a child perceives their family and is likely to appeal to younger children or those at an earlier stage of development. After explaining to the child that you want to know more about their family, show them some pictures of different facial expressions, making sure they understand each expression and the emotion it relates to. You could draw them yourself or use a professional set. I recommend the Todd Parr Feelings Flash Cards which are really attractive and accessible for young children. They’re also thick, sturdy and, most importantly, durable. For more developed children, you can select a wide range of expressions; for those at earlier stages of development, you might want to just use two or three (ie happy, sad and angry). There are many other activities that are effective in direct work with children and young people. I will try to write more posts soon. Follow me on facebook or twitter so you don't miss them! In the meantime, you might like to take a look at Audrey Tate’s book, Direct Work with Vulnerable Children. It’s primarily a set of playful activities to create opportunities to engage children. Through these activities children are enabled to tell their stories and provide Social Workers with assessment and support opportunities. I've written a couple of posts recently about Protecting Young Children Online and Protecting Big Kids Online. I was thrilled at how many times they were viewed and shared (Thank you!) and I hope they have helped you to feel more confident in safeguarding your children in the digital age. Since I last posted I've found the new Fire HD Kids Edition. It has some great easy-to-use parental controls where you're able to manage usage limits, content access and educational goals, plus there's a 2 year worry free guarantee! It looks fab! Children’s apps and websites were in the news on privacy grounds earlier this week, after the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) announced a review of how these services collect data on their young users. It will form part of an international project, coordinated by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, and will look at 50 websites and apps, particularly what information they collect from children, how that is explained, and what parental permission is sought. The websites and apps will include those specifically targeted at children, as well as those frequently used by them. So how can parents decide which sites, apps and games are appropriate? Today I was emailed about the NSPCC's updated Net Aware guide which helps parents to understand what their children are doing online and hopefully maintain open channels of communication. It's a huge database providing information on sites, apps and games. It tells you what it is, why kids like it and provides an age rating to help parents judge whether it's appropriate for their child. After having a look through the site I realised that I probably haven't heard of half of them before.  Research by the NSPCC earlier this year found that many parents have gaps in their online knowledge and don't talk about the right issues with their children. For example, Tinder, Facebook Messenger, Yik Yak and Snapchat were all rated as risky by children, with the main worry being talking to strangers. However, for the same sites the majority of parents did not recognise that the sites could enable adults to contact children. Although eight out of ten parents told the NSPCC that they knew what to say to their child to keep them safe online, only 28% had actually mentioned privacy settings to them and just 20% discussed location settings. One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication. Here are my top tips:

Take a look at the NSPCC guide and let me know what you think. I was overwhelmed at the positive response I got for my earlier post about Protecting Young Children Online (Thank you for sharing!) so as promised I am following up with one for older children in Key stage 2. The tips below should be used in addition to the security measures outlined last time. Of course, you might want to give them access to a greater range of websites now that they are older; however, you should still ensure that they are age appropriate. Technology and the internet has changed a lot since we were kids and keeping up to date can be a challenge. Many parents feel overwhelmed as their children’s technical skills seem to far exceed their own. However, children and young people still need support and guidance when it comes to managing their lives online if they are to use the internet positively and safely. There are a number of books and online resources available to increase your technical knowledge and skills. If you aren't that confident online or with electronic devices it might be worth brushing up now before the kids really surpass us in their adolescent years. Is your child safe online? A Parents Guide to the internet, facebook, mobile phones & other new media is a great starting point. It covers all forms of new media - iPhones, apps, iPads, twitter, gaming online - as well as social networking sites. If you want to learn more of the techie stuff behind maintaining personal privacy Internet Privacy For Dummies is a really accessible quick reference guide. Topics include securing a PC and Internet connection, knowing the risks of releasing personal information, cutting back on spam and other e–mail nuisances, and dealing with personal privacy away from the computer. The UK Safer Internet Centre offers a Parents' Guide to Technology. It introduces some of the most popular devices, highlighting the safety tools available and empowering parents with the knowledge they need to support their children to use these technologies safely and responsibly. The NSPCC and NetAware have also created a brilliant resource detailing sites, apps and games that they have reviewed. It's a huge database telling you what they are, why kids like them, and it gives an age rating to help you to judge whether it's appropriate for your child. Anyway, back to protecting your big kids... One of the best ways of safeguarding your child online is to maintain open channels of communication.

It’s never too early or late to start talking to your child about staying safe online. There are a number of great resources available for parents and professionals to access and download. On my earlier post I showed you Smartie the Penguin by ChildNet. For children in key stage 2 there’s The Adventures of Kara, Winston and the SMART Crew. It’s a cartoon and each of the 5 chapters illustrates a different e-safety SMART rule.  is for keeping safe. Be careful what personal information you give out to people you don’t know  is for meeting. Be careful when meeting up with people you’ve online chatted to online.  is for accepting. Be careful when accepting attachments and information from people you don’t know they may contain upsetting messages or viruses.  is for reliable. Always check information is from someone reliable and remember some people may not be who they say they are.  is for tell. Always tell a trusted adult if something or someone online is making you worried or upset. You can watch the full movie online or download it to a device for later. For children at the older end of this age group, CBBC has an online comedy drama called Dixi. Dixi both encourages children to enjoy the creativity of the internet while also getting them to think about the potential dangers of social networking, from online privacy and safety settings, to the real-world consequences of cyber bullying. Cheryl Taylor, Controller of CBBC, says: “It’s important to raise awareness about safety online and Dixi does this in an engaging, educational and entertaining way”. There are also games that complement the drama for children to access through their website. You could also sit down together to watch the film below by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre. It’s called 'Jigsaw' and is suitable for this age group. It helps children to understand what constitutes personal information and enables children to understand that they need to be just as protective of their personal information online, as they are in the real world. It also directs them where to go and what to do if they are worried about any of the issues covered. It could be a great conversation starter and open up the channels of communication. I hope that you find this helpful. It can be a little intimidating when our children venture into the virtual world but with support and boundaries they will have have access to a resource with huge educational and social value. I'll post again soon with tips for supporting Teenagers / Young People in the digital age. Please follow me on facebook so that you don't miss it!

|

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|