|

Recently I’ve been posting about attachment after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argued more should be done by health and social care providers to train key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality. Firstly I outlined the origins of attachment theory and then went on to detail some of the current debates. Over the years I have read many assessments of children and their families in which workers have assessed attachment as being ‘good’ as the child had been seen “happy and smiling”. In the serious case review of Peter Connelly it is noted that the social worker reported “he had a good attachment to his mother, smiles and is happy”. Two months later a second social worker reported “a good relationship between the child and his mother” despite him head-butting the floor and his mother several times. These behaviours in and of themselves are not indications of attachment. In instances of abuse, smiling may be a learned defence mechanism which they have developed to put their carer at ease thereby making them safer. It is, therefore, important that Social Workers develop skills to correctly assess attachment and its impact upon a child’s internal working model. I have already touched upon Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation in my previous posts but will go into a little more detail here. NICE recommended in their draft guidance that practitioners should consider the use of the ‘Strange Situation Procedure’ for children aged 1-2 years, and a modified version for 2-4 year-olds. The procedure is used in a controlled setting and practitioners observe the child’s response to two brief separations from, and reunion with, the parent. The child’s responses are then categorised as fitting one of three patterns of behavioural organisation:

Take a look at the following YouTube video by The New York Attachment Consortium to see how these behaviours manifest in practice. Children’s’ responses in this situation are considered to reflect the history of interactions the child has experienced in the home. However, research has found that on occasion and child’s Strange-situation behaviour does not fit well into the criteria of any of the given classifications as described by Ainsworth. It is therefore, important that practitioners do not ‘force’ a child into the ‘best fitting’ attachment classification. It may, in fact, be that a number of different, coherent and distinct responses are possible. Disorganised or disorientated behaviour is one further classification that has been identified and is seen by Social Workers in cases of abuse. These behaviours can be identified when a child finds themselves in anxiety-provoking situations into which an abusive caregiver enters. As the child does not know what to do they experience “fear without solution” and practitioners will observe simultaneous displays of contradictory behaviour patterns. NB. when using the Strange Situation procedure it is important Social Workers are mindful of the fact that behaviour could be a function or neurological or other difficulties experienced by the infant as an individual, having little to do with relational issues between parent and child. Recent research has moved away from observations of behavioural interactions between infants and parents, like the Strange Situation, and Social Workers should also be concerned with how attachment experiences become organised in memory into “models” of relationship expectations. This shift reflects a recognition of the important role that internal working models play throughout life. They form the “schemas” that predispose a child to perceive social relationships in terms of past experiences. Any assessment should also, therefore, be interested in understanding how children form and organise internal working models of attachment experiences.  Social Workers have for many years relied on play as the primary medium of communication as it provides a compensating medium for limitations in children’s verbal abilities. Additionally, the expression of emotionally charged adverse experiences often makes direct verbal communication more difficult for children, and Social Workers are sensitive to this. Using dolls, the Story Stem Assessment Profile asks children to respond to a set of narrative story stems where they are given the beginning of a ‘story’ highlighting everyday scenarios with an inherent dilemma. Children are then asked to ‘show and tell” me what happens next?’ This allows some assessment of the child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles, attachments and relationships, without asking the child direct questions about their family which might cause them conflict or anxiety. If you are going to employ this technique I would recommend that you use dolls that are ‘neutral’ like these from Melissa and Doug. Using figures from known television programmes could encourage the child to script the story in a way that is congruent with the toys ‘character’ rather than their own internal working model. Clinical training in this technique is available through the Anna Freud Centre in London. I hope you have found my posts helpful and interesting. They contain just a fraction of the information provided through professional training and I would recommend practitioners incorporate this into their continuing professional development plan. I will add a further post soon about assessing attachment in older children. Please follow me on facebook or twitter to catch it.

0 Comments

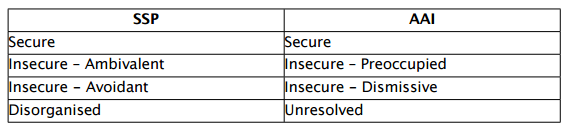

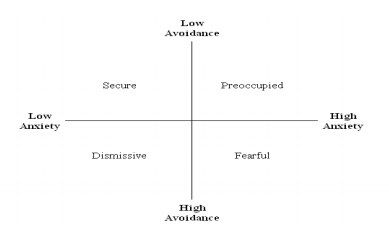

Yesterday I posted about the origins of attachment theory. Draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argue that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. My personal experience of the Social Work Masters was that attachment was covered but in a rather one dimensional manner without the necessary critical analysis. In recent years, some assumptions have been challenged and this post will look at three of the main debates in the theories of attachment. These debates are ongoing and you will have to judge for yourselves. Adult attachment styles are dictated by the mother-child relationship. This assumption rests on the principle of monotropy, but recent reconceptualisations of attachment suggest that attachment might be more significantly influenced by multiple caregivers and relationships. There are three possible models: Firstly, the Hierarchical model is the classic understanding of attachment theory, in which attachment is to a primary caregiver (the mother) and that this relationship is concordant with other attachment relationships, and mediates future relationships. This model derives from Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s research. Secondly, the Integrative model describes an alternative organisational structure in which the child integrates all of his/her attachment relationships into a single representation. In this model, by Van IJzendoorn et al. (1992) they suggest that all attachment relationships are equal and independent, and the quality of the combined relationships best predicts his/her developmental consequences. The entire extended network of attachments is a better predictor of attachment than family attachment style only. Thirdly, the Independent model states that each attachment relationship brings an independent representation with qualitative differences, domain and person specific. For example, the child’s relationship with peers is more likely to be determined by the maternal attachment, whilst social competence, efficacy and adjustment is more likely to be determined by paternal attachment. The evidence for this model is less well-established, but Crittenden’s Dynamic Maturational Model uses a version of this as its basis (more on that later). There is evidence, both for and against these models using cross-cultural studies, studies of attachment in adolescence, and inter-generational studies. It's probably too much to cover right now but I may cover it in another post at a later date. A categorical classification system is the most accurate way to describe attachment styles. The two most significant attachment measures are the Strange Situation Protocol, used with toddlers, and the Adult Attachment Interview. Both allocate individuals to one of four categories. If you’re interested in finding out more about your own attachment style you might like to look at this online version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale, a test of attachment style. The ECR was created in 1998 by Kelly Brennan, Catherine Clark and Philip Shaver. It groups people into four different categories on the basis of scores along two scales. The inventory consists of thirty six that must be rated on how characteristic they are of you. If you do complete the above questionnaire, you will be given a classification made on the basis of a dimensional conceptualisation of attachment, that looks like the one below. Fraley & Spieker (2003) have argued that this provides a more sensitive and ecologically valid assessment of individual attachment style. Finally, Patricia Crittenden has elaborated further by creating a model of attachment called the Dynamic Maturational Model. Crittenden’s model assumes multiple frames of reference and context-dependent responses, centred around a cluster of sub-categories. So, instead of the individual being categorised, the individual has a set of strategies, which can be matched to a range on this sphere. She adheres very strongly to an evolutionary framework. To see an overview of her theory, take a look at this YouTube video where she gives a presentation, titled "The development of protective attachment strategies across the lifespan", at the BPS DCP Annual Conference in 2012: Attachment style is set by 12-18 months

Bowlby’s original theory implied, partly by its focus on a single caregiver, that attachment style might be set quite early on, although he explicitly allowed for life events and circumstances to allow change. However, it was Ainsworth’s development of the Strange Situation Protocol that really reinforced the idea that attachment style is set by the time of primary individuation at or around 18 months. There is evidence to support this stability of attachment style, but it is not black and white. Different studies have found that:

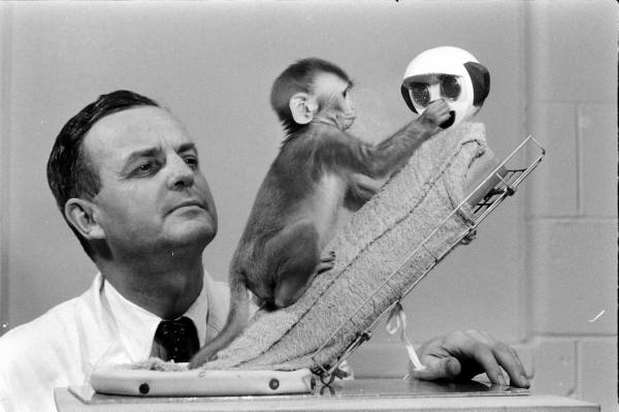

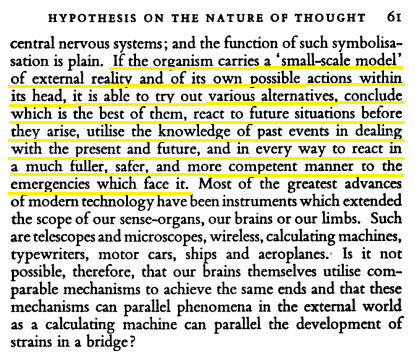

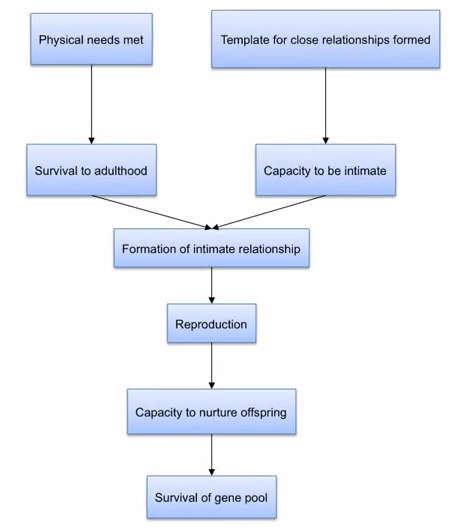

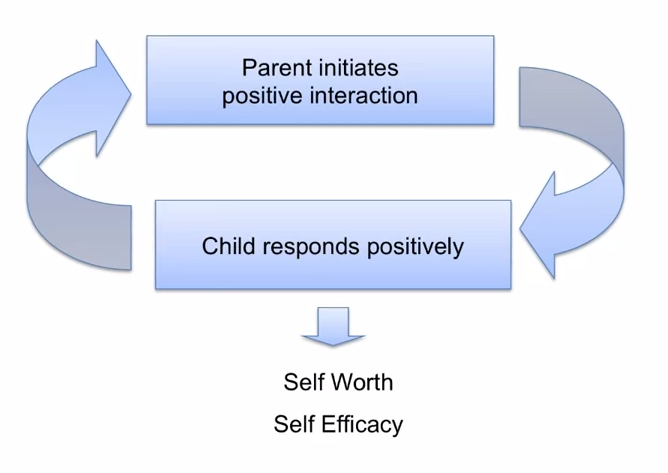

So, attachment classification certainly has predictive power, but not 100%. In adoption studies (See my previous post on Risk, Resilience and Adoption), children adopted before 12 months of age are only slightly more likely to be insecurely attached than children raised in birth families, whilst children adopted after 12 months are at significantly higher risk of insecure attachment, and disorganised attachment specifically. There are many, many more debates around theories of attachment. Too many to cover in a short blog post. However, I hope this has given you a tiny introduction to current thinking around the topic. It is important that practitioners are aware of these issues so that they can assess for themselves how best to integrate them into practice. Unfortunately, I can't give you a definitive answer about which theory or approach is best. You'll need to make an educated judgement based upon your own knowledge, research and professional experience. All social workers in the care system should be trained in recognising and assessing attachment, according to proposed guidelines. The draft guidelines by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) argues that health and social care providers should train all key workers in assessing attachment difficulties and parenting quality, for children in – or on the edge of – care. I couldn't agree more and I'm a little disappointed that this isn't already the case. This post, covering the origins of attachment theory, will be the first in a short series on attachment and it's implications for social work practice. Attachment theory is almost 75 years old. During this time, some elements have changed but the underlying principles remain as true now as then. In the 1940s and 50s John Bowlby worked with children who had been either separated from their parents as war orphans or evacuees or who had experienced significant adversity in their early life. He believed that these children went on to experience a range of emotional, behavioural and psychological difficulties as a result of their early experiences of loss and trauma. Bowlby has been criticised for developing a normative theory of development based on non-normative experiences. He was trained in a psychoanalytic tradition, but was disillusioned by its intrapersonal focus; instead he was influenced by the important empirical discoveries happening around the same time. I’ll outline some of them below: In his 1943 book, The Nature of Explanation, Kenneth Craik described the central nervous system as “a calculating machine capable of modelling or paralleling external events” and saw this as a basic feature of thought. He described the human or animal in this way: This might seem obvious to us now but to John Bowlby it provided a pragmatic explanation to the adverse developmental outcomes he had seen in orphans and institutionalised children; more so than the psychoanalytic training of his background because Craik’s theory was outward looking; seeing the individual in context. John Piaget described intellectual development as a process of adjustment and adaptation to the world. As part of this growth children have to go through a process of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation involves the inclusion of new information into existing schema or internal working models. Accommodation happens when a child is not able to assimilate information into an existing schema and either has to change the schema or develop a new one. Craik and Piaget were important for attachment theory because they explained how infants develop schemas or maps for future relationships based on prior experiences and learning.  Niko Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz were ethologists studying the sociology of birds. Their careers travelled in parallel, influencing each other along the way. Lorenz was inspired to conduct a study involving goslings which ultimately led to the imprinting hypothesis. In this study Lorenz split a large hatch of goslings, leaving half with the mother and taking the other half and raising them himself. Over the course of their development the goslings quickly identified him as their primary attachment figure and followed him, copying his behaviour. He taught them to swim, he used to call them with a special horn for feeding time and they always followed him. When they were given the opportunity to return to their birth mother, they didn’t recognise her as such, instead preferring Lorenz. This taught us about the importance and probable biological nature of the bond between mother* and offspring, in which the mother, the primary attachment figure, is the one who provides physical and emotional care and nurture. As a light break, you might enjoy the following Tom & Jerry cartoon where they, in a very flippant and simplified manner, explain the concept of imprinting. Later, in the 1960s Harry Harlow carried out a series of lab based experiments on monkeys (seen at the top of this post), rearing them in total social isolation. The study, which was unquestionably cruel, showed that monkeys were preferentially seeking out a cloth mother for nurturing; spending up to 18 hours a day holding onto her and seeking out a wire mother only for food. All the means for a healthy development were available and yet the monkey showed severe damage as a result of their experiences. The study suggested that mammals need reciprocal nurturing and attachment as much as they need their physical needs met. Bowlby hypothesised that since humans cannot survive without adult care our evolutionary history has selected pre-wired dispositions on both the part of the adult and the child that ensure human survival. From this basis, Bowlby developed a model of attachment that is monotropic (has a single attachment figure). It’s focussed on survival of the individual and the species and is integrated with human development to both influence broader developmental outcomes and be influenced by individual and contextual factors. Within this model tasks are identified for care giver and child that promote reciprocity and ultimately autonomy. The goal is to maintain emotional and physical equilibrium of the child thus keeping their attachment systems settled, allowing exploration and learning. During periods of distress the attachment system is activated and takes priority over the exploratory system. The regulation of emotion and behaviour are tasks that the care giver and child accomplish together through reliable, responsive and consistent care giving. The care giver provides the infant with the necessary up-regulation and down-regulation that the infant needs. Consequently, parents that are not attuned to the infants needs, and cannot reliably and consistently provide care, leave the child without the necessary external regulatory support. Over time this develops into a complex system which affects the way in which a child, and eventually adult, responds to their own needs and to those other others.

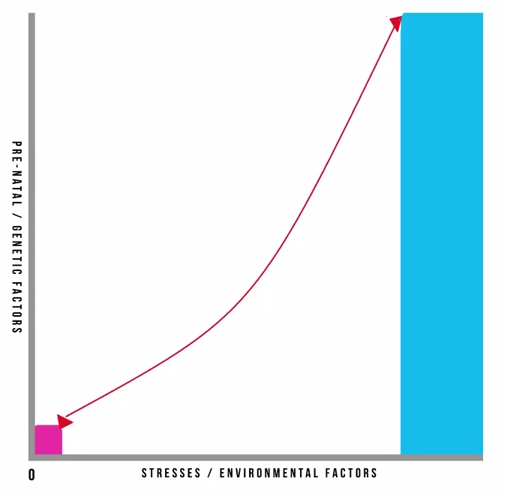

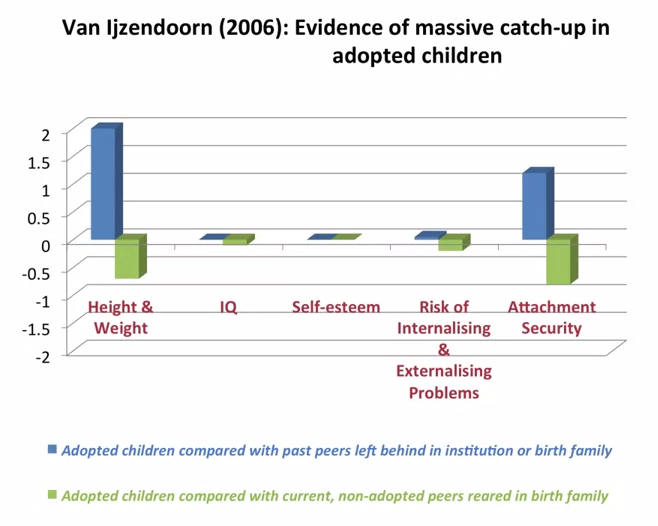

I hope you've found this post interesting. You might also be interested in my post on Attachment Based Family Therapy. I'll write more on the current debates in attachment and methods of assessment soon. Follow me on facebook and twitter so you don't miss them. Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

Adolescent 'behavioural problems' are a huge source of referrals for local authority children's services across the country, after parents and teachers struggle to find strategies that work. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that many rebellious and unhealthy behaviours or attitudes in teenagers can actually be indications of depression. The following are just some of the ways in which teens “act out” or “act in” in an attempt to cope with their emotional pain:

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) has been the traditional route for support in the UK. However, waiting times and thresholds are at an all time high. More and more services are commissioned only for those children presenting with the signs and symptoms of a diagnosable disorder or condition which means that those struggling with less obviously acute or harder-to-label problems are often not eligible for treatment. As a result Children’s Social Workers are increasingly working to help families through what can be a very distressing time, and there is a renewed focus on specialised training to meet this need.  Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) is a manualised, empirically informed, family therapy model specifically designed to target family and individual processes associated with adolescent depression. However, I have found it has strong applicability when working with all families with teenagers. It was first developed by Prof. Guy Diamond, Suzanne Levy and Gary Diamond; all of whom have received international acclaim for their work in this area. The model is emotionally focused and provides structure and goals; thus, increasing the Social Workers intentionality and focus. It has emerged from interpersonal theories that suggest teenage depression can be precipitated, exacerbated, or buffered against by the quality of interpersonal relationships in families. It is a trust-based, emotion focused model that aims to repair interpersonal ruptures and rebuild an emotionally protective, secure-based, parent-child relationship. Teenagers may experience depression resulting from the attachment ruptures themselves or from their inability to turn to the family for support in the face of trauma outside the home. The aim of ABFT is to strengthen or repair parent-child attachment bonds and improve family communication. As the normative secure base is restored, parents become a resource to help their child cope with stress, experience competency, and explore autonomy. I believe it should be integrated into the practice of all children’s social workers. If you’d like to learn more you can buy the latest book, Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Depressed Adolescents, here. |

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|