|

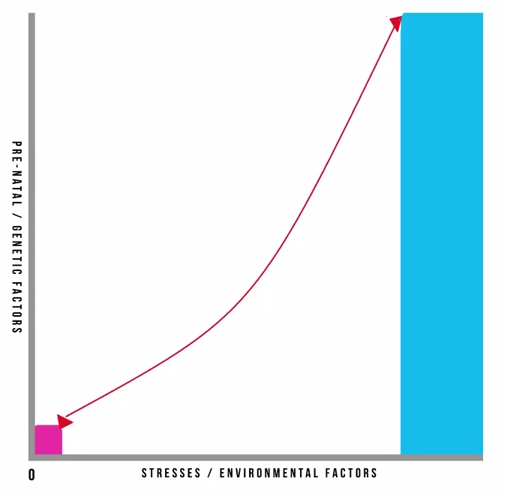

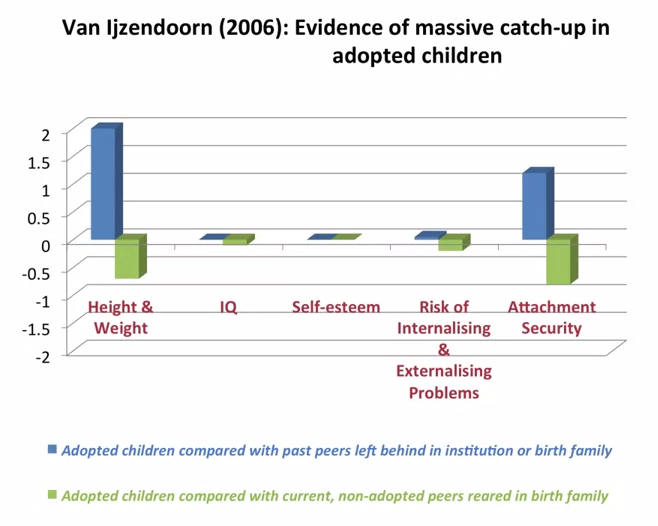

Originally researchers and practitioners imagined that resilience was born out of some temperamental factor, innate to a person and not amenable to change or intervention. Temperament was one of those factors but there are other important factors including education, cognitive ability, social support and economic resources. In the second wave of resilience research theories of psychology started to come to the fore. Researchers incorporated theories of developmental psychology, considering the effects of timing in interaction between the different developmental variables. This allowed for a more subtle understanding of resilience in which trajectories were not foretold but could be influenced by the addition or subtraction of key variables. In the third wave, resilience research started to focus on intervention to improve outcomes. This is a challenging area to study as resilience interventions can have distil outcomes in a range of different domains, not all of which are predictable. For instance, an intervention focused on education improvement might lead to a child one or two generations down the line not growing up in poverty. In the fourth and current wave of research, existing findings have been reconsidered in the context of new data on genetics and neurobiology. This information provides us with new way to describe and analyse existing data rather than providing causal explanations per se. One example of how gene/environment interaction research is influencing our understanding of risk and resilience is the theory of differential susceptibility put forward by Jay Belsky and Michael Pluess. They noted, as has also been seen in clinical and research practice, that children experiencing the same risks and the same environmental stresses were having differential outcomes. They queried whether the diathesis-stress model could adequately explain these variations. Pre-natal and genetic risks are individual factors included on the Y axis whilst stresses or environmental influences are captured on the X axis. This is a classic model and has helped to inform many theories in clinical psychology. It also underpins political agendas around resourcing interventions in the early years of a child’s life. It is however, in its simplest format here, problematic. It gives the impression that stresses affect an individual in accumulative fashion, ignoring the effects of timing and development, the nature of stresses or concurrent resilience factors. The model focusses on many negative outcomes ignoring the moderating effect of positive influences. Belsky and Pluess noted that what was additionally missing from this model was a recognition of the role of individual plasticity. Plasticity is a term used to describe the ability of the brain and its bio-behavioural network to respond to new information. Infants have high plasticity in order to accommodate new learning and develop rapidly. As we get older plasticity diminishes. An example of this is the capacity of a five year old versus a fifty-five year old to learn a new language. For the five year old this is an easy task with learning happening almost unconsciously. For the fifty-five year old acquisition of a new language will be possible but challenging, even with very deliberate learning. When we include the concept of plasticity in our understanding of risk and resilience we make some interesting new discoveries. It also teaches us the importance of thinking about positive and negative influences and outcomes together. So, if we imagine a child who has experienced some significant adversity and yet appears to be coping we describe them as resilient and, indeed, they don’t suffer a catastrophic fall in the face of their difficulties but instead manage to maintain a reasonably even keel, perhaps even managing to make some slow progress along normative developmental lines. This child’s ability to resist the worst effects of the negative environment protects them; however, it also means that they don’t get the full benefit of a positive environment. In contrast, some children don’t fare so well. In the face of adversity they have catastrophic outcomes. These children are called non-resilient. However, an important detail is being missed here. These children are showing plasticity in their development. In the face of a negative environment their outcomes are poor so they’re susceptible to the influences around them. What this also means is that if we give these children a positive environment with good resources they have to potential for a favourable outcome. So, what puts them at risk of an adverse outcome also gives them the opportunity of an incredibly positive outcome, and they may actually achieve more than those children who we’ve traditionally labelled as resilient. Adoption is widely regarded as an effective intervention for children who’ve been born into families where there are significant risks associated with abuse, neglect, domestic violence, substance use or other multiple risks that prevent 'good enough' parenting. For children where there is the prospect of repatriation back into the family through improvements in parenting, fostering or institutional care can provide a good compromise position. However, children who have been fostered or are institutionalised tend to show high insecurity and attachments and general delays in development, suggesting this is not the best final solution. In that respect, adoption provides a much better option. Nonetheless we know that adopted children can have problems afterwards: they make slower progress at school; have more behavioural problems during middle childhood; and are more likely to be referred to child and adolescent mental health services. In light of this IJzendoorn and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis, including 230,000 children who had been adopted or remained with their birth families, fostered or institutionalised to examine outcomes in height, weight, IQ, self-esteem, internalising problems; externalising behavioural problems; and attachment security. What they found was what they describes as massive catch-up, particularly noticeable in height and weight but also IQ. Self-esteem showed no difference to children brought up in their birth families. Externalising problems were slightly more prevalent. Attachment security was lower than that for birth children at 47% compared to 60-70% in birth family children. But that is still twice as high as children who had been fostered or institutionalised. They concluded that adoption is a highly effective intervention building resilience and mitigating against the risks of an early challenging childhood 'if no other solutions are available'. Of note, this mata-analysis just looked at adoption as an intervention and because it covers a lot of studies we can cancel out the effects of more specialist or therapeutic interventions. Therefore, what we can see is that adoption has dramatic outcomes for children, reducing risk and increasing resilience.

0 Comments

|

AuthorI'm a Qualified Children's Social Worker with a passion for safeguarding and family support in the UK. Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|